As the Europeans expanded their imperial domains across the globe in order to secure lucrative commodities, they colonised lands that were vastly different to their home countries, with the climate being the most pressing difference as it affected how people lived, the gastronomy and the animals that inhabited there.1 In this context, the primary account written in 1804 by George Leith, the first Governor General of Prince of Wales Island, known as Penang Island in the present day will be used as a centrepiece to illustrate the biased and flawed attitude the Europeans had towards the tropics and how this source ties into the wider theme of tropicality.

Given that the account was published during the time the British were seeking to expand their hold overseas to dominate trade under the Napoleonic Wars, cutting French supplies and establishing a foothold in the Malacca Straits was a top British priority as stated in the source.2 In order to make the colony functional, the British had to build infrastructure and provide amenities for the both the coloniser population, new immigrants and the locals. In the source, Leith explicitly states that the island is abundant with water and soil, the harbour is well shielded by the Malay peninsula, overlooks the Straits of Malacca, has reasonable high altitude hill retreats to escape the dry season, and the biggest settlement, George Town has brick buildings, hospitals, roads and houses which implies a sign of modernity. By stating all those factors, it can be assumed that Leith is attempting to encourage settlement on the island as all those factors make it attractive for colonists looking to maximise their profits in an expanding empire. Secondly, he notes how the island has a reasonable climate as compared to India. This point strikes me because, in the secondary readings, it was often assumed that the Indian subcontinent was the epitome of ‘tropical romanticisation’ due to its abundant natural resources and relative similarities to how the British or other Europeans envisioned a ‘tropical society’ where there are abundant resources and good weather.1 By shining the island’s potential in a positive light, it allows the Europeans to see that its climate is favourable and suitable for economic investment. This is in stark contrast to my elective secondary source reading on French Indochina, in which the French saw their colony as a deathbed with a 2% death rate and that the average life expectancy of a Frenchman is only around the 40s as the colony was filled with diseases.3 As a result, the ‘tropical climate’ or European colonies with hot weather can vary from being romanticised as a paradise or described as a place filled with disease and ‘bad air’ like how the French saw Indochina. As a result, the tropics are often ‘imagined’ in the European mindset.

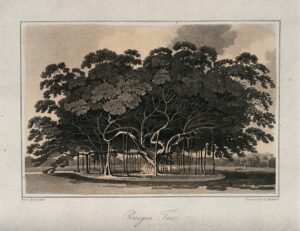

Leith explicitly classifies occupations and characteristics of certain races in a sub-section called Inhabitants. He describes the Chinese, Parsees and Chooliahs as the races doing most of the hard work and are well-behaved which makes them useful as coolies and labourers to successfully run a colony. Conversely, he describes the Malays as indolent, vindictive and treacherous because they are an uncivilised race and are useless for labour. This signifies that inhabitants in the tropics are often seen by the Europeans are more lazy which is based on ancient Greek ideas of how the hotter the climate, the lazier and less warlike an individual becomes as illustrated by Hippocrates.4 This signifies that ‘tropicality’ is not based on science but rather supported by pseudo-philosophy by ancient philosophers like Hippocrates which do are not grounded in scientific methods and create a racial division line that separates races according to their ‘usefulness’ and perceived ‘nature’. Therefore, it is evident why ‘tropicality’ is a flawed and biased concept. In the case of the British Strait Settlements, the British like Leith perceived that the Malays are lazy and uncivilised, Chinese and Indian labour had to be bought in from other colonial possessions in order to maximise profits, thus altering the settlement pattern and demography of present-day Malaysia and Singapore.

To sum it up, the concept of ‘tropicality’ is biased in the sense that it was based on pseudo-science, assumptions and, imaginations hence making it flawed.

- Arnold, David John. The Tropics and the Travelling Gaze: India, Landscape, and Science, 1800-1856 Introduction + Ch 4 From the Orient to the Tropics [↩] [↩]

- Leith, George, Sir, A short account of the settlement, produce, and commerce, of Prince of Wales Island, in the Strait of Malacca [↩]

- Jennings, Eric Thomas. Imperial Heights: Dalat and the Making and Undoing of French Indochina Ch 1 Escaping Death in the Tropics [↩]

- Hippocrates v. 1 ‘Airs Waters Places’ XII-XVI pp. 105-117 [↩]