The Shanghai Race Club was much more than just a place for horse racing. Founded in 1862, the club quickly became one of the most prominent social and cultural centres in Shanghai, attracting some of the city’s wealthiest and most influential residents. For nearly a century, from 1862 to 1951, the Shanghai Race Club was a hub of socialisation, where attendees could gather to mingle, dine, dance, and enjoy a variety of cultural and sporting events. This blog post will explore the spatial practices of a typical Raceday at Shanghai during this fascinating period in the city’s history. Such a spatial approach provides a unique window into the social and cultural dynamics of Shanghai during this time.

It is the autumn of 1924. It’s Raceday. The day everyone has been waiting for. The crowd in the enclosure is decked out in the finest and most elegant styles of the Art Deco period. Anticipation for the Champions’ Stakes is bubbling, with a sense of electricity and excitement rippling through the air of Old Shanghai. This scene, one of the most famous from the time of Treaty Port China, is a magnificent lens through which to understand social practices and how people, of different classes, genders and ethnicities mingled and interacted.

Ning Jennifer Chang’s ‘To See and Be Seen: Horse Racing in Shanghai, 1848–1945’, is a wonderful text that captures that unique element of the typical Raceday in Shanghai. This being that the act of going ‘Racing’ is as much about the spatial practices of the enclosures, the bars and the dining rooms than it is about the running of the horses themselves. The spectacle was a product of the attendees themselves; the way they dressed, behaved and put on a show. Chang’s chapter captures the significance of ‘being seen’, the outward portrayal of a positive, and often opulent and lavish image, that would heighten social status and your perceived position of class. Dressed in ‘divine millinery’ and ‘dainty dresses and lovely ducklings of bonnets’, the ladies attending appear to have been especially concerned with this external image.

James Carter’s brilliant ‘Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai’ also captures the vibrance of Raceday at Shanghai. He writes that ‘Champions Day was Shanghai: stylish and obscene, bigoted and cosmopolitan, refined and ragtag.’2 This excerpt seizes the juxtapositions that would have been clear on the day. The whole of Shanghai had come to watch; different classes, genders and ethnicities all in the enclosure together, all rushing to the bookies to place a bet, all rushing to the bar to get one more drink. Chang notes that on one occasion in 1878, 20,000 Chinese people attended, a figure amounting to 10% of the total Chinese population of Shanghai.3The enclosure, a relatively small space for watching the races, would have had people huddled closely together, everyone visible to one another and all open to each other’s scrutiny and judgment.

Despite the buzz of the enclosure, elites still had the privilege of private dining and drinking. Owners’ boxes provided a more exclusive space for ‘elaborate meals and freely flowing champagne.’4 Fur coats and the latest fashions were strutted, whilst ever more alcohol was consumed in what must have been a similarly raucous atmosphere. Carter’s book highlights how important the fashion was to the scene of the day. Miss Ing Tang (pictured below) was a fashion designer who made clothes specifically for the Raceday. Her designs and their popularity reveal that ‘the day should be not just about sports but also about the Settlement’s social scene of sophisticated, sometimes, orientalist styles.’5

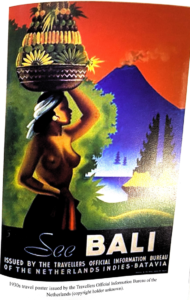

One only has to visit the Cheltenham Festival or Ladies Day at Royal Ascot to understand and grasp the link that racing has with style, grandeur and elegance. It continues to capture the imaginations and offer many the chance to display their class, high-taste and social status. This is confirmed by Chang who writes that ‘Horse racing was not the only thing worth watching. During the two seasonal meetings held each year, the area around the edge of the racecourse became a temporary leisure space, and for those few days, it would be like a Chinese festival or a Western holiday’.7 The Race Club during this era provides another example of Shanghai’s trendsetting style. Although a Western import through the Treaty Port arrangement, the city embraced not only the sport of racing, but also its culture of socialising, gambling and drinking. In concurrence with the cabarets, dance halls and jazz that defined much of the social liberation and moderation of this period, racing and its fashion had a huge influence on the changing cultural landscape of Shanghai.

It is important to note the autonomy that this space provided otherwise constrained groups. Women were arguably the biggest beneficiaries, with the chance to express themselves in high style. Moreover, women from all walks of life were able to attend, with the admission fee being inexpensive. Chang has also expressed the view that ‘Within this space, the most attractive aspect was that men were allowed to watch women without restrictions regardless of whether they were decent women or courtesans from Shanghai’s brothels.’8 Thus, equally, the men in attendance benefited from the female presence, too, with the enclosure offering a unique spatial environment for interaction and courtship.

As it turned out, the smart money in 1924 was on Bonnie Scotland to win the Champions’ Stakes as it ran comfortably home by a few lengths. Not that anyone was paying too much attention. The real show was the effervescent champagne social taking place the other side of the rail. The day out at the Race Club was an archetypal element of Shanghai’s cultural liberation during this period, one which did not discriminate and one which excited the entire city.

- https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/shanghai-race-club [↩]

- James Carter, Champions’ Day: The End of Old Shanghai, (New York, 2020), p. 22 [↩]

- Ning Jennifer Chang, ‘To See and Be Seen: Horse Racing in Shanghai, 1848–1945’, in The Habitable City in China: Urban History in the Twentieth Century, (London, 2017), p. 96 [↩]

- Carter, Champions’ Day, p. 22 [↩]

- Carter, Champions’ Day, p. 86 [↩]

- Carter, Champions’ Day, p.86 [↩]

- Chang, ‘To See and Be Seen, p. 97 [↩]

- Chang, ‘To See and Be Seen, p. 98 [↩]