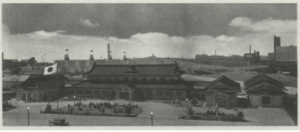

The puppet state of Manchukuo, created in 1932, was advertised by the Japanese Empire as a state “autonomous from Western influence”.1 This narrative was consistently reinforced through exhibitions, pamphlets and films produced by the Japanese government. To reinforce this narrative on a global stage, the Japanese invested a small portion of their exhibit at the World’s Chicago Fair in 1933 through a Manchuria exhibit in partnership with the Southern Manchuria Railway Company (fig.1). Concurrently, an American exhibit of the Golden Temple of Jehol (fig. 2), a province invaded by the Japanese Kwantung army and also an annexe of Manchuria at the time, was an expensively replicated and highly popular exhibit at the fair.2 This article uses Shepherdson-Scott’s work on the World’s Chicago fair supported by pamphlets and images of the event to illustrate that political diplomatic pursuits were consolidated through visual displays of authority.2 These imaginaries of Manchurian and Chinese territories served to assert specific narratives about contested legitimacy of Japanese authority in Manchuria at this time.

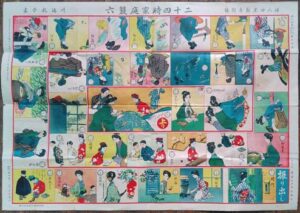

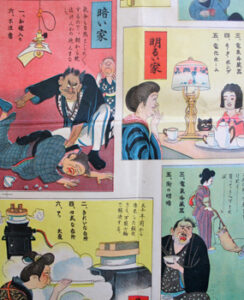

Defined by Young as the ‘Jewel in Japan’s Imperial Crown’, Manchukuo developed into a significant and profitable portion of the Japanese empire, however, public knowledge in the US about of the role of Japan in Manchukuo was controlled, Manchukuo was not recognised as a state by the US government and Japanese involvement in this territory was considered aggressive.3 Soft power, this is co-opting rather than coercion, in the form of elements of Japanese culture such as Japanese gardens or the exportation of travel guidebooks and pamphlets to private tour companies across Europe and the United States was widely accepted and proliferated in public discourses on Japan. In contrast, the acclimatisation of western audiences to imaginaries of Japanese Imperial power was confronted and countered by the US. Images of Japan were only accepted in the form that they were presented to a western audience when they were a exotic or visually appealing, thus, the trustees of the A Century for Progress fair capitalised on this reality by exoticising the Temple of Jehol and reinforced its Chinese heritage and the sovereignty of China. By challenging Japanese associations with the Manchurian Railway company and its assimilation of ‘Manchukuo’ into Japanese notions of modernisation and mobility, the temple of Jehol publicly rebuffed the relevance of the Japanese occupation of Manchuria and intertwined national politics corporate public relations within the context of the fairground.2

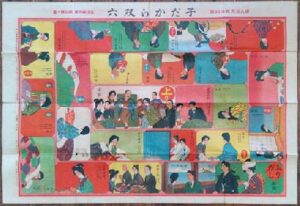

Figure 1: Illustration of the Japan Exhibition complex, Manchurian pavilion is visible on the far right (1933-34).4

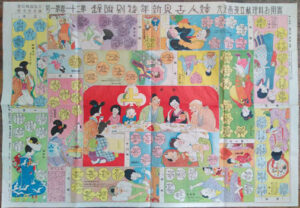

Figure 2: The golden Temple of Jehol at the Century of Progress World’s fair 1933-34.5

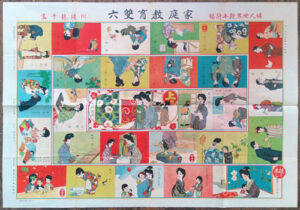

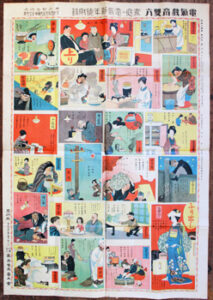

Figure 3: Cover of the Brochure for the Southern Manchuria Railway exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933.6

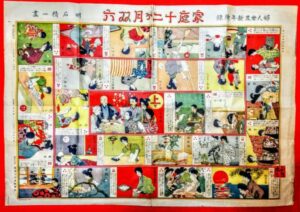

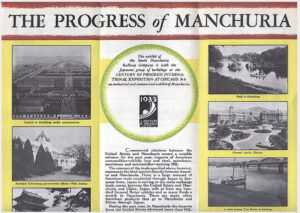

In this period following the 1931 ‘Manchuria Incident’ when the legitimacy of Manchukuo and the role of Japanese occupation and the Kwantang army still proved to be an elephant in the room, these displays of consolidation and reputation by the Japanese and the US governments respectively reflected the sumbilinal power play between the two nations over the legitimacy of Japanese dominance in Manchukuo.2 In the official Southern Manchurian Railway brochure (fig.4), relations between the US and Manchuria regarding trade is phrase neutrally, ”Japan is serving as the major trade exchanger between the United States, and Manchuria and China” and yet it still alludes to Japanese hegemony in the region.7 Moreover, images in the brochure include, the capital city under construction by the Japanese, the Japanese Kwantung Army Government offices, and the central circle of government buildings in the capital, Changchun.8 In contrast to the cultural statement in the form of the temple of Jehol which gained significant praise for its dazzling quality and drew attention from visitors because of its beauty, the presentation of the Manchuria exhibit focused on acclimatising the American audience with Japan as an intermediary between the US and China/Manchuria. Whilst the temple challenged the political borders of Manchukuo and the authority of the Japanese exhibition, the production of knowledge that associated Japan with significant political and economic stakes in Manchuria’s capital and infrastructure and the physical positioning of the Manchurian exhibit within the Japanese exhibition proved to be a spatially powerful illustration of their authority in the region and their goals for the future.

Figure 4: Brochure for the Southern Manchuria Railway exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933.6

In conclusion, the overt retaliation against Japanese constructions of Manchukuo at the Chicago World’s fair by the American embassy illustrate the limits applied to Japanese overseas diplomatic pursuits. The competing narratives created by the US to challenge Japanese assertions of Imperial power highlight that beyond military and policy based rebuttals of Japanese occupation of Manchuria in the early 1930’s, alternative and creative challenges to Japanese power were established within the public eye designed both to covertly manipulate public opinions of the power of the Japanese government but also to intimidate Japanese authority on foreign soil.

- Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism (London, 1998), p.1, p.22. [↩]

- Kari Shepherdson-Scott, ‘Conflicting Politics and Contesting Borders: Exhibiting Japanese Manchuria at the Chicago World’s Fair, 1933-34’, The Journal of Asian Studies 74:3, (2015), pp.539-564. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Young, Japan’s Total Empire, p.22. [↩]

- Illustration of the Japan Exhibition complex, Manchurian pavilion is visible on the far right (1933-34), A century of Progress exposition in Chicago, 1933-34. Accessed at: Yale University Library. [↩]

- Image of The golden Temple of Jehol at the Century of Progress World’s fair 1933-34, Accessed at the Art Institute of Chicago, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/235402/golden-temple-of-jehol (Accessed 5/02/2024). [↩]

- Cover of the Brochure for the Southern Manchuria Railway exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933, Available at: http://travelbrochuregraphics.com/blog/2014/01/09/brochure-south-manchuria-railway-from-the-1933-chicago-worlds-fair/ (Accessed: 05/02/2024). [↩] [↩]

- Brochure: Southern Manchurian Railway form the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, Available at: http://travelbrochuregraphics.com/blog/2014/01/09/brochure-south-manchuria-railway-from-the-1933-chicago-worlds-fair/. (Accessed: 05/02/2024). [↩]

- Brochure for the Southern Manchuria Railway exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933, Available at: http://travelbrochuregraphics.com/blog/2014/01/09/brochure-south-manchuria-railway-from-the-1933-chicago-worlds-fair/ (Accessed: 05/02/2024). [↩]