This blog post will explore how Mary Pratt’s argument of imperial nations using an ‘anti conquest’ narrative to disguise their colonial presence is applicable to the Dutch colonial force’s advertisement of Bali as an ‘island of paradise’. As Pratt explains in the chapter ‘Narrating the anti-conquest’ within her book Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, ‘anti-conquest’ refers to the strategies of representation that European bourgeoisie subjects use to secure their innocence whilst simultaneously asserting European hegemony.1To demonstrate the concept, Pratt explores how naturalists used a rhetoric of ‘anti-conquest’ within their travel writings of the Cape Colony to legitimise imperial powers’ actions and takeovers of the region.2As this blog post will show, in the early 20th century, the Dutch government also adopted an ‘anti-conquest’ rhetoric within their depiction of Bali as a tourist destination through brochures advertising the nation as an ‘island of paradise’ to disguise and hide their aggressive takeover of the island.3

The Dutch conquest of Bali was a lengthy and bloody battle, with the Balinese people proving a tough force to defeat. When Bali was eventually conquered following the death march of the Balinese rajas after the puptans of 1906-8, the Dutch invaded Bali and killed off or exiled much of the population, destroying everything. As Adrian Vickers explores in Bali: A Paradise Created, the Dutch massacres contrasted significantly to the ‘liberal imagination of the Netherlands’ thus, in the aftermath the Dutch government was concerned with how their actions would impact their international standing.2 As a result, the Netherlands were eager to find a way to present their new colony internationally whilst not exposing the nation’s colonial atrocities. This can be seen through their advertisement of Bali as an international tourist destination which can be analysed as an example of Pratt’s concept of an ‘anti-conquest’ rhetoric.

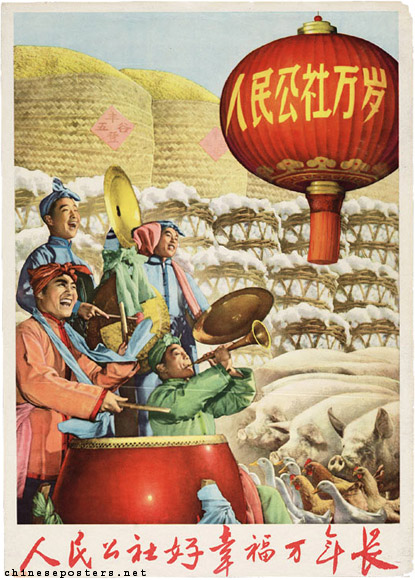

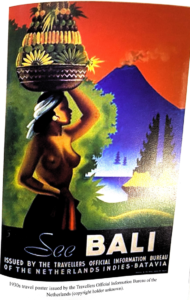

In 1914, only six years after the Klungkung puptan, the first tourist inducements to visit Bali were published. They began with the Dutch steamship, the KPM, issuing the first tourist brochures of Bali. These brochures advertised Bali as the ‘Garden of Eden’, an island that featured ‘jungle scenery, palm trees and rice fields’ untouched by modernism.4 The brochures communicated an image of Bali that did not refer to any violent or imperial expansionist policies. Instead, they portrayed the Dutch colonisers as the ‘protectors of culture’. The account and ‘gaze’ of Bali that was transmitted as an official discourse suggested and publicised that the Dutch’s presence was uncontested. As one can see from the brochures (see figure. 1 and figure. 2), they intently focus on landscape and nature descriptions. They use visual imagery to remove both the Dutch as European antagonists from the image of Bali and the presence of any indigenous Balinese settlers that opposed the Dutch’s presence. This depiction aligns with Pratt’s ‘anti-conquest’ as the examples of travel writing she explores emphasis that the ‘anti-conquest’ consists of rhetorics that narrate a sequence of sights and seeing that focus on the landscape and minimises the European presence.5 Alongside the ‘anti-conquest’ rhetoric guiding the international ‘gaze’ away from the possibility of any colonial atrocities, Vickers notes that the advertisements were also seen as a way to ease the Dutch’s consciences. It not only allowed them to control the international narrative and image of the island but within official circles helped secured the nation’s innocence.

Figure 1: 1930s travel poster from KPM

Figure 2: 1930s travel poster issued by the Travellers Official Information Bureau of the Netherlands

The brochures not only featured natural landscape and scenery, they also included a significant focus on half-naked Balinese women. This further illustrates the tourist brochures aligning with Pratt’s concept of ‘anti-conquest’. As Pratt explores, the ‘female figure of the “nurturing native”’ has often been a key in sentimental versions of the anti-conquest.6 This figure of the half-baked Balinese woman was so key to the KPM’s tourist advertisements that Bali became known as ‘a land of Woman’.7 Again, this evidences the advertisements promoting a gaze of Bali that depicted the island as a utopia hiding the exploitation or violence that underpinned the Dutch’s presence reinforcing how the advertisements should be seen as an example of Pratt’s concept of ‘anti-conquest’.

In conclusion, as Pratt highlights, it is ‘only through a guilty act of conquest can the innocent act of the anti-conquest be carried out’.8 In the Netherlands’ attempts to absolve themselves of the guilt and potential international backlash that existed from their bloody imperialist conquest, they used tourist brochures to promote a gaze of Bali rooted in the rhetoric of ‘anti-conquest’. Their advertisements of Bali focussed on natural images and the exotic, attractive nature of Balinese women which minimise or avoided the publication of their aggressive European presence and maintained the innocence of Dutch hegemony.

- Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 58. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩]

- Adrian Vickers, Bali: A Paradise Created (Victoria: Penguin Books, 1989), 130. [↩]

- Ibid., 131. [↩]

- Pratt, Imperial Eyes, 60. [↩]

- Ibid., 96. [↩]

- Vickers, Bali: A Paradise Created, 132. [↩]

- Pratt, Imperial Eyes, 66. [↩]