In this short visual analysis, I will argue that the distinctive phases of architectural style visible in the architecture of Changchun and Xinjing illustrate the Japanese state’s search for an international modern style to characterise Manchukuo as a ‘utopian’ state. Space within the cities was used to portray the technical capability of the Imperial government whilst also appealing to Asian sentimentally.1 Young emphasises the speed and proficiency with which the Japanese puppet state introduced railway lines. Indeed, over 5,030km of new track was built between 1932 and 1938 and the resultant rapid formation of railway towns and cities.2 Similarly, running water, underground sewage systems, gas and electricity were efficiently introduced during the construction of Manchukuo’s cities.3

Whilst these elements of city planning were clearly defined necessities within Japanese conceptions of ‘utopia’, the style, organisation and decoration of state and public buildings was a more complex process of evolution, trial and error. The utopian vision following the Manchurian incident in 1931 sought to establish the state of Manchukuo as a source of mutual benefit and liberation for the Japanese colonisers and the Chinese colonised.4 Whilst Japanese commercial enterprise was prioritised, the Architecture of Changchun and Xinjing reflected Chinese revivalism and the emergence of Manchurian style in the search for the ideal ‘utopian’ structure and facade. The design and implementation of these structures are used to implement order. They demonstrate the manipulation of European styles as a means to connect with Western merchants and the inclusion of Chinese and Manchurian styles to encourage cultural mixing to align with the ideals of a modern, cohesive society.5

Figure 1: Manchukuo’s Hall of State6

Figure 2: Manchukuo’s Ministry of Public Security.7

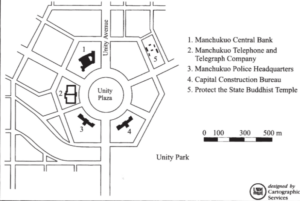

Figure 3: Unity Plaza8

The construction of a ‘utopian’ vision for the puppet state of Manchukuo was realised through assimilating Chinese architecture with a modern Japanese style.9 The scale of the state buildings constructed in the Manchurian style used symmetry to reflect a desire for a utopian balance and harmony between the Chinese and Japanese inhabitants of the city.10 The conflation of Japanese and Chinese building practices alongside the sheer size of these state buildings functioned as Japanese propaganda by emphasising the capabilities, power and legal monopoly of Japan over Manchukuo. Significantly, this blend of European columns and stonework with Asian roofs instilled notions of Asian superiority over the European style to create Xinjang’s bureaucratic expressions of Manchukuo as a ‘utopia’.

Asian Revivalism was an architectural style that aimed to mask Xinjing’s initial period of architectural chaos, these buildings were often characterised by a Japanese-styled roof.11 This building style was referred to as the “Manchukuo bureaucratic building style”.12 The Hall of State, built between 1934 and 1936 was designed by Ishii Tatsure and contained a pagoda-style roof flanked by two similar roofs at the end of the central section of the buildings.13 Freestanding columnar entryways positioned beneath the capped roofs also separated also distinguished the Hall of State from previous styles14 Columns appear in fours throughout the wings and central structure of the building, enhancing the European-inspired element of verticality.6. Similarly, the Ministry of Public Security also sported capped sloping tiled roofs. Built between 1935 and 1945, it is of note for housing the Manchukuo military headquarters.15 These buildings began the initiation of a “rising Manchurian style” notable for its implementation of verticality and the adoption of Japanese-style roofs with exposed roof gable.7

These buildings surrounded the ‘Unity Plaza’ (depicted in figure 3), a 36-metre wide extension to the SMR settlement that conformed to the grid pattern of the SMR settlement and was designed to reinforce elements of national architectural heritage and was named to imply the unity of the various groups, Manchu, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese which formed Manchukuo.16 Unity Avenue, a 36-metre wide road extending from Unity Plaza, was a site of consistent ceremonial celebration where thousands gathered for mass meetings throughout the 1940s in support of Japan’s wars in Asia.17 The construction of these broad plazas and large authoritative Bureaucratic administration buildings reflect the significant role of urban planning and constriction to the state regulation of Manchukuo and the role of “Asian Revivalism” in attempting to create a modern harmonious city. As Buck asserts, Chinese residents of Xinjing continued to experience subordination throughout the puppet states’ influence over Manchukuo18 Indeed, these works of architecture reflect the tensions between the ideological harmony desired by the intelligentsia and their understanding as ‘utopia’ as the consideration and inclusion of ethnic groups that lived in Manchukuo and the harsh imperial reality of the motivations of the Japanese government.

- Bill Sewell, Constructing Empire: The Japanese in Changchun, (Toronto, 2009), p.76 [↩]

- Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, Twentieth-Century Japan, (Berkeley, 1999), p.244. [↩]

- Young, Japan’s Total Empire, p.245. [↩]

- Ibid, p.242 [↩]

- Sewell, Constructing Empire, p.79 [↩]

- Ibid, p.84 [↩] [↩]

- Ibid, p.85 [↩] [↩]

- David Buck, “Railway City and National Capital: Two faces of the Modern in Changchun” in Joseph Eshwick (ed), Remaking the Chinese city: Modernity and National Identity, 1900-1950 (Hawaii, 2000), p.83. [↩]

- Young, Japan’s Total Empire, p.241 [↩]

- Sewell, Constructing Empire, p.87 [↩]

- Ibid, p.81 [↩]

- Ibid, p.81 [↩]

- Ibid, p.82 [↩]

- Ibid, p.83 [↩]

- Ibid, p.85 [↩]

- Buck, “Railway City and National Capital”, p.84 [↩]

- Ibid, p.86 [↩]

- Ibid, p.88 [↩]