In the late 1920s, Nanjing was chosen as the capital city of the Republic of China as the Guomindang (GMD) embarked on its mission of ‘national reconstruction.’1 The individual at the forefront of this endeavour was Sun Yat-sen, a revered Chinese revolutionary leader, who dreamt that Nanjing would become a central hub of progress and modernity. A large group of individuals were instrumental in helping Sun Yat-sen dreams come true, but Y.Y Wong is a standout individual who requires significant attention. By delving into his fascinating body of work, we can unravel the captivating narrative of Nanjing’s urban development and, more profoundly, gain insight into Nationalists’ pursuits of modernity.

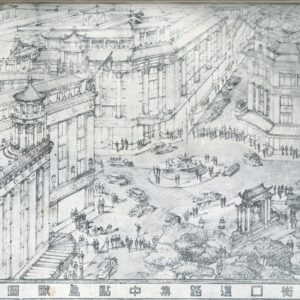

Figure 1. Wong, Yook-Yee, Plans for the New Nanjing Capital, 1929, Two Years of Nationalist China (1930)

Figure 1., presents Y.Y Wong’s designs for the new Nanjing Capital in 1929, which is an interesting blend of Western architectural principles harmoniously intertwined with traditional Chinese aesthetics. At first glance, one is struck by an array of characteristics that might be expected when viewing places such as Washington D.C., London and Paris. Indeed, the sense of order and fluidity created by the architectural structures was an international standard, and one that Nanjing’s city planners hoped to replicate.2 Moreover, on closer inspection the image showcases structures that resemble Chinese characteristics, notably the upturned roofs in majority of the buildings. This fusion of modern western characteristics and classical Chinese motifs was a revolutionary in the realm of Chinese architecture.

A noteworthy feature of this image is the arrangement of the windows on the buildings. This detail is discussed by Charles Musgrove in his article ‘Building a Dream: Constructing a National Capital in Nanjing 1927-1937,’ as he highlights how the windows adhered to standardised patterns and were interspersed with rows of stone columns, which symbolised European and colonial neoclassical style.3 Indeed, as much of Musgrove’s article exclaims, Nanjings’ city planners were learning from Western sciences to help move into an era of modernity. The work of Y.Y Wong underscores the influence of spatial planning, not only in shaping physical landscapes but also in imbuing them with symbolism to help achieve governmental agenda.

Significantly, the time that this drawing was produced was during a pivotal juncture in China’s history with the establishment of the GMD. At the core of their mission was ‘national reconstruction,’ and Nanjing was at its epicenter. Indeed, throughout China’s dynastic history, rulers frequently employed spatial reorganisation as a means to reinforce their political authority, and the GMD were no exception.4 They ushered in a new cosmology, which established fresh conceptions of Chinese modernity and national identity.

It is crucial to note, that Y.Y Wong’s plans were not entirely replicated and Sun Yat-sen’s dreams were never lived, due to wider political and economic issues that came to fruition in the late 1930s and 1940s. From this one incontrovertible truth emerges: socio-political development is far more complex and nuanced process than often assumed, and therefore warrants close consideration.

Despite failure to fully implement the dreams of Y.Y Wong and Sun Yat-sen, Nanjing did undergo urban development through the creation of broad boulevards, the implementation of sewer systems, urban zoning, and the displacement of thousands of residents which profoundly altered its urban landscape.3 This did, in turn, create a new Chinese society, but one that had been influenced and shaped by western ideals of modernity; which leads one to a question of what China is. This iterates the need to understand what connects nation and urban place and, perhaps, what can be best deciphered from the case of Nanjing and Y.Y Wong’s drawing is that the creation of place is not static or an independent event but an active and multifaceted process.

- Carmen Tsui, ‘State Capacity in City Planning: The Reconstruction of Nanjing, 1927-1937,’ Cross-currents: East Asian History and Cultural Review, 1:1 (2012). [↩]

- Charles Musgrove, ‘Building a Dream: Constructing a National Capital in Nanjing 1927-1937’, in Joseph Esherick (ed)., Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900-1950 (2002), p. 142. [↩]

- Mungrove, ‘Building a Dream,’ p. 148. [↩] [↩]

- Marijn Nieuwenhuis, ‘Producing Space, Producing China: A Critical Intervention,’ Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation (2012), p.5. [↩]