Cambodia, a country located on the Indochinese peninsula in Southeast Asia is often referred to as a hidden gem for international tourists. With bordering countries Thailand to its west, Vietnam to the east and Laos to the north, Cambodia is constantly overshadowed by both its western and eastern neighbours as Thailand has been known to international tourists for decades and Vietnam has been known for its long war with America and a rapidly growing economy in recent times.1 As democracy is restored to Cambodia, its rich history, especially the globally renowned UNESCO world heritage site of Angkor Wat has attracted millions of tourists every year and has even featured on the current national flag of Cambodia despite the fact that it was discovered when Cambodia was under French rule.2 This blog post will compare how an old foreign travel account from The Geographical Journal written by Lord Curzon in the 19th century and a 2023 Chinese travel agency’s article views Cambodia and what sites they feature prominently. After doing a brief comparison with Bali, the article will conclude that the images of tourism in Cambodia are shaped by power dominance given how it remains a poor state and that the nationality of the individual writing about it plays a key role in shaping narratives about the country.

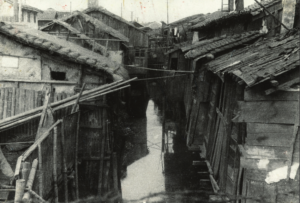

The first account from The Hon. Lord Curzon, a prominent British politician published in The Geographical Journal published in 1893, it details his travels across French Indochina in what is now Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. In his account, he generalises the lives of Cambodians as native and exotic as he notes how swift they are at building wooden huts on top of the Tonle Sap Lake. First, following the French colonial administration, he reinforces the account of the ‘Indochinese’ people by dividing them into categories. He describes the ‘natives’ as more effeminate and shorter in stature the deeper south you go and that the landscape is abundant with crops and crops.3 Subsequently, he describes their eating habits as ‘barbaric’. This demonstrates that at that time when not much technology was around, tourism was limited to the upper class and that generalised accounts, especially by the privileged like Lord Curzon were seen as authoritative and acceptable to be published in magazines like The Geographical Journal. Next, he offers a description of a travel itinerary from Phnom Penh to Angkor Wat. The journey he undertook involved riding on a French steamship and then embarking by land on oxen carts and sampans operated by native Cambodians. Following up, he offers a brief description of the ruins on how they illustrate a once-glorious empire now being controlled by the French and under constant threat from invasion by the Siamese (present-day Thailand).4 This indirectly justifies imperialism and showcases the weakness of Cambodian culture as by showing the ruins of an extinct great empire, it shows how the power is now rested in the French, that is controlling Indochina and the Siamese, who resisted colonialism and constantly putting pressure on French interests in the region. As a result, it can be seen that in the heyday of imperialism, travel was limited to the colonial elite and native cultures of the people under European control were subject to exoticisation and generalisation.

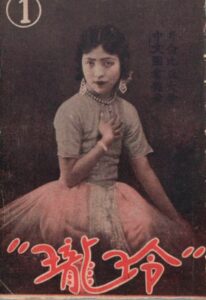

Fast forward to the 2020s, Cambodia, although managing to free itself from colonialism and the horrors of the Khmer Rogue with its strong economic growth, its development standards lagged behind global standards. In place of the French, the Chinese now have a strong presence in the region as part of its Belt and Road Initiative to provide infrastructure aid to developing nations across the world to achieve its status as a great power.5 Although it was claimed that the investments were to benefit Cambodia’s growing economy, it has raised concerns among experts that Cambodia is becoming too dependent on China and that China is attempting to use its economic might to chip away at Cambodia’s sovereignty.6 By looking at tourist numbers by nationality, China ranks third after Vietnam and Thailand as the largest source of tourists outside of Southeast Asia.7 In the travel guide published by China International Travel Service Guilin Co. Ltd, it lists out the top sites for travel in Cambodia, which not suprisingly Angkor Wat appearing on the top, then it advertises certain Buddhist temples, the royal palace in Phnom Penh and numerous beaches along the southern coast with a short paragraph stating Cambodians as pure and nice.8 Unlike Lord Curzon’s account which describes Angkor Wat and the people of Cambodia in detail, the Chinese account simply just lists out sites that are culturally ‘Cambodian’ in nature and a complete guide to Cambodian cuisine. Furthermore, the account states that the friendliness of Cambodians and the affordability nature of the country is definitely a reason to visit the country. This demonstrates how with changing geopolitics and modes of travel, the nature of tourism also changes, and in the case of the Chinese, they are the main power influencing Cambodia.

What is interesting to me is that the Chinese site leaves out the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh. I believe that the reason is because in order to court Chinese investments, the current Cambodian government, filled with members from the brutal Khmer Rogue regime (1977-1979) is making an effort to downplay anything that will contribute to angering China hence showcasing how bilateral relations often shape the style of tourism.

Linking to the compulsory readings, I see parallels with the case of Cambodia with Bali not too far away. Similar to Cambodia, Bali was under Dutch colonial rule and subject to international accounts exoticising its culture.9 Bali was also subject to having its narratives controlled by external forces as while the Dutch conquered it, it was seen as savage, but after pacifying it, the Dutch played a key part in creating images of ‘Peaceful Bali’ by demonstrating its unique mystical characteristics and ornate temples. Even after independence, the multi-cultural state of Indonesia actively promoted Bali as a peaceful paradise for foreigners to attract economic activity while the natives barely got a voice in the construction of their identity. This elucidates how the Dutch colonial government and the Indonesian government all played a part in exoticising Balinese culture similar to what the European travellers and Chinese government did to Cambodia. In short, power plays a part in shaping tourist narratives.

- https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2014/oct/28/-sp-cambodia-tour-two-weeks-holiday-itinerary [↩]

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/668/ [↩]

- Curzon, George N. “Journeys in French Indo-China (Tongking, Annam, Cochin China, Cambodia) (Conclusion).” The Geographical Journal 2, no. 3 (1893): 193–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/1773660. [↩]

- Curzon, George N. “Journeys in French Indo-China (Tongking, Annam, Cochin China, Cambodia) (Conclusion).” The Geographical Journal, vol. 2, no. 3, 1893, pp. 193–210. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1773660. Accessed 26 Jan. 2024. [↩]

- https://china.usc.edu/what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-means-cambodia [↩]

- https://www.rfa.org/english/news/cambodia/substitute-07232020153513.html [↩]

- https://www.thestar.com.my/aseanplus/aseanplus-news/2023/11/30/foreign-tourist-numbers-skyrocket-in-cambodia#:~:text=This%20marked%20an%20increase%20of,%25)%2C%20expanding%20by%20497.5%25. [↩]

- https://www.citsguilin.com/article/gonglue/jianpuzhailvyougonglue.htm [↩]

- Vickers, Adrian Bali: A Paradise Created (2012 [1996]) [↩]

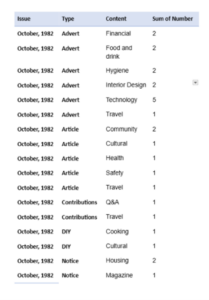

Image 1.

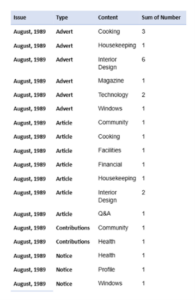

Image 1. Image 2.

Image 2.

Figure 1. the manifestation of foot binding

Figure 1. the manifestation of foot binding In 1909, Russian botanist Vladimir Mitrofanovich Arnoldi visited the Buitenzorg Botanical Gardens. Though he was primarily concerned with the contributions of the gardens to botanical knowledge and rarely commented directly on politics, we can see in his account the footprint of the Dutch colonial project.

In 1909, Russian botanist Vladimir Mitrofanovich Arnoldi visited the Buitenzorg Botanical Gardens. Though he was primarily concerned with the contributions of the gardens to botanical knowledge and rarely commented directly on politics, we can see in his account the footprint of the Dutch colonial project.