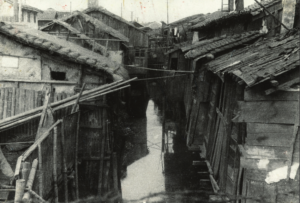

Image 1.1 The shantytown in Shanghai

Image 1.1 The shantytown in Shanghai

Image 2.2 Lilong in Shanghai

Image 2.2 Lilong in Shanghai

This blog explores the prevailing conditions of Shanghai’s shantytown and lilong between 1930 and 1950. It will explore the demographic composition of residents, the quality of buildings, and the overall living standards, in order to highlight how these contrasting residential areas epitomised the prevailing social hierarchy in Shanghai. The shantytown primarily served as hubs for individuals from the lower strata of society, reflecting their challenging living conditions. Conversely, lilong represented spaces where the social elite and respectable members of society resided, manifesting the progressive strides of the era. These distinctions were tangible reflections of the societal disparities within the hierarchy.

To depict the authentic realities of Shanghai’s shantytowns (Image 1) and lilong (Image 2), this blog draws from Hanchao Lu’s depiction of lilong and Wang Lanhua’s firsthand experiences as a resident of Fangua Lane, a renowned shantytown in 20th-century Shanghai. The visual representations above vividly illustrate the stark contrasts between these prevalent residential areas. The shantytown exhibited a worn-down appearance, while lilong boasted a sense of orderliness and thoughtful design. However, these disparities extended far beyond mere surface appearances.

Primarily, the demographic makeup of residents in these areas was notably distinct. Shanghai experienced a significant influx of migrants after 1930, significantly complicating the city’s demographic landscape. According to Lu, Shanghai’s population surged to over 3 million in 1930, a drastic increase from the approximately 1 million residents in 1900.3 This surge in population affected both the shantytown and lilong, albeit in different ways. The shantytown, such as Fangua Lane, predominantly became sanctuaries for refugees, exemplified by the experiences of Wang Lanhua and her husband. As Denise Ho highlights, the post-1945 civil war brought a significant influx of refugees to Shanghai, resulting in Fangua Lane accommodating between 3,000 to 4,000 shantytown residences inhabited by over 16,000 refugees.4 Wang Lanhua notably referred to these shantytown dwellings as gundilong 滚地龙, the symbolic portrait of working people’s lives in Old China.5 In contrast, lilong experienced an influx of predominantly elite residents, including rich landlords, merchants, literati, bureaucrats, shop assistants, clerks, schoolteachers, and artisans.6 Despite the influx of migrants, social class remained a determining factor in residents’ choice of dwelling, ultimately shaping the demographic landscape of these neighbourhoods.

The contrast between the amenities and facilities in the shantytown and lilong was also stark. The shantytown dwellings were often constructed from random materials, and subject to frequent demolitions. As noted by Wang Lanhua, usually, she would put up a shelter each night and take it down each morning in order to avoid the International Settlement police.7 In sharp contrast, lilong residences boasted sturdy reinforced concrete structures,8 offering greater security and durability, making them less susceptible to easy demolition. This architectural contrast was also reflected in a broader divide in interior facilities. From the 1930s onward, lilong houses underwent a modernisation surge, integrating modern amenities such as sanitary fixtures (bathrooms with a bathtub and flush toilet) and a gas supply for cooking and hot water.8 Additionally, some residences began incorporating garages, indicating the residents’ ownership of private automobiles.9 In contrast, shantytown dwellings lacked modern conveniences and endured harsh conditions. Wang Lanhua’s poignant account indicated that she gave birth to her second child on the mud floor of a gundilong.10 While lilong residents embraced modernisation and its benefits, shantytown inhabitants lived with simplicity and austerity, devoid of such amenities. These differences in material convenience are the practical expression of the class distinction.

The stark disparities between the shantytown and lilong, evident in their demographic composition and housing facilities, underscore a substantial gap between these residential areas. Life in the lilong, without a doubt, epitomised comfort, modernity, and convenience, starkly contrasting the perpetually turbulent, arduous, and austere existence in the shantytown. The demographic composition of the residents is the best evidence of the social stratification, as it directly reflects the eventual flow of Shanghai’s migrant population. Moreover, the contrasting housing amenities in the shantytown highlighted the physical manifestation of the class stratification. Lilong houses were equipped with modern conveniences, a material practice of higher social status. This contrasts with the humble facilities of the shantytown buildings. As the essential residences for Shanghai’s transient population between 1930 and 1950, the shantytown and lilong epitomised the living conditions of different social classes. A comparative analysis of these areas can help to gain a comprehensive insight into the living conditions of different social strata in Shanghai during that period.

- Straw huts over stagnant water source: H1-21-8-21, Shanghai Municipal Archive, <https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Straw-Huts-over-Stagnant-Water-Source-H1-21-8-21-Shanghai-Municipal-Archives_fig4_278821830> [accessed November 22, 2023]. [↩]

- Hanchao Lu, Beyond the Neon Lights: Everyday Shanghai in the Early Twentieth Century (Berkeley, 2008), p. 147. [↩]

- Lu, Beyond the Neon Lights, p. 162 [↩]

- Denise Y. Ho, Curating Revolution Politics on Display in Mao’s China (Cambridge, 2018), pp. 65-67. [↩]

- Ho, Curating Revolution Politics on Display in Mao’s China, p.65. [↩]

- Lu, Beyond the Neon Lights, p. 156. [↩]

- Ho, Curating Revolution Politics on Display in Mao’s China, p.79. [↩]

- Lu, Beyond the Neon Lights, p. 150. [↩] [↩]

- Ibid., p. 151. [↩]

- Ho, Curating Revolution Politics on Display in Mao’s China, p.67. [↩]