This article uses interviews with Pan American Airways’ air stewardesses who worked between 1960 -1980 alongside images and advertisements to argue that Japanese women had to embody their image as “visions of excellent, attentive service and pampering” in the eyes of many Americans in order to mobilise themselves in the postwar era.1 Many Japanese women who engaged with international travel felt they were being “split apart in the space between two cultures”, however, the Pan Am stewardess lifestyle gave them the opportunity to establish company sponsorship or marriage through which they could maintain their overseas residency status. Once these women had experienced the mobility and profitability of the American aviation industry, avoiding the discriminatory Japanese job market, which prioritised age over competency when hiring women into entry level employment for which they were substantially overqualified, became a source of discomfort and a motivation to emigrate.2

Figure 1: The First group of “Nisei” stewardesses, 1955.3

Yano’s chapter “Flying Geisha” succinctly explains how the image of the geisha stewardess consolidated the Pan American Airlines brand in the 1960s by capitalising on nostalgic, racialised western stereotypes of Japanese women as subservient.4 During the rise of second wave feminism in Euro-America, the stereotype of the dutiful, submissive women Japanese woman embodied nostalgia for many western men and therefore women began to performed this stereotype for a western audience during their career with Pan Am.5. Equally, the financial independence and subsequent freedom from dependence on the Japanese, patriarchal job market experienced by the stewardesses at Pan Am performed as an enclave thorough which they were able to escape.

Figure 2: First Japanese stewardesses in an article from The CLipper, 1966.6

The “new woman” discourses proliferated an image of anxiety for the established patriarchal post-WW2 economy in the Euro-American market and the Japanese alike. However, due to Pan Am monopolising on the eroticisation of Japanese women by Western consumers, middle and upper class Japanese women who spoke fluent English were able to insert themselves into the aviation industry and for the first time, earn a competitive salary en par with educated Japanese men.7 In order to exert resistance against their exclusion from the deeply entrenched gender hierarchy of the Japanese workplace, they instead engaged with the racialized and exoticized power of Western companies and their customers.8 Japanese companies rarely higher end women for positions of responsibility midcareer, or at any stage.9 Conversely, paying in dollars, Pan Am offered Japanese stewardesses a salary almost five times larger than their male counterparts with the same level of education.10 With access to a competitive income and global travel, Pan Am’s ‘flying geisha’ had accessed the flexibility of internationalism as a movement affiliated with feminism, providing these women with mobility which surpassed that of many western women form a similar level of wealth and education.11 The limits of internationalism emerged from the cultural isolation and sense of feeling adrift between Japanese and American culture. By adopting what Kelsky describes as a ‘deterritorialised imagination’ as a result of their international careers, women like Yamamoto Michiko developed a ‘“need-to-marry syndrome” who described the prospect of marrying her American boyfriend as the “key to [her] life”. (Quote form Kelsky, Women on the Verge, p.211.))

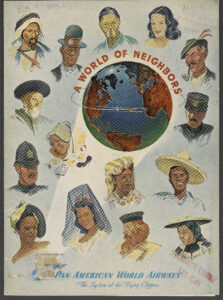

Figure 3: “A World of Neighbours” an advertisement from Pan Ams 1946 Brochure.12

“There were a lot of girls that used to say, “I don’t speak the language, but I only look like I speak the language!” – “Nisei” Stewardess, Pan American Airways 1955-1986.13

Some Japanese American Pan Am stewardesses only undertook Japanese language screening invigilated by a non-Japanese speaker, and as long as the women were able to phonetically read Japanese, they met the requirements illustrating the prioritise of Pan Am were looking Japanese and speaking a little. These were the requirements to fulfil the racialised position illustrated that these women were performing the discourse of the subservient, submissive Japanese woman through visual appearance alone.14 Pan Am prided themselves on having “one “Oriental” or Asian flight attendant on each flight”. A Chinese Pan Am flight attendant commented that, “They [Pan Am] use you… As long as they have Oriental face”.15 In the Jet Age, Pan Am marketed itself as an international carrier by using Asian stewardesses, fluent or not, to establish an exoticism’s “international” atmosphere.16 Thus, as depicted Pan Am’s “A World of Neighbours” advertisement, the company was attempting to establish itself as the provider of the essence of each nation to which it flew to (fig. 3). By establishing the troop of the “Flying Geisha” in the 1960s and 1970s, Pan Am evoked the nostalgic figure of the submissive Japanese women to counteract the emerging image of second wave Euro-American feminists.17 Within the ‘contact zone’ of the jet, where cultures clashed and asymmetrical power dynamics emerged between nations, the glamorous, exotic stewardess provided a feminised stereotype designed to calm the western audience.5

To conclude, the Japanese “flying Geisha” evaded one patriarchal institution whilst feeding into another. Within the compact space of the airplane, an exciting commercial transportation vehicle which was perceived as the gateway into the post-war modern age, these women were able to take advantage of exoticised, racialised stereotypes of Japanese women to access the more lenient employment prospects available in the American market. Ultimately these women relied on a racialised performance of traditional femininity to access substantial mobility in an age of consumption.

- Yoshiko Nakano, “Japan’s Postwar International Stewardesses: embodying Modernity and exoticism in the Air”, US-Japan Women’s Journal, no. 55/56 (2019), p.82. [↩]

- Karen Kelsky, Women on the Verge: Japanese Women, Western Dreams (Durham, 2001) p.206. [↩]

- Christine Yano, Airborne Dreams: “Nisei” Stewardesses and Pan American World Airways (Durham, 2011), p.66. [↩]

- Yano, ‘”Flying Geisha”‘, p.86. [↩]

- Ibid, p.88. [↩] [↩]

- Image taken from, Christine Yano, Airborne Dreams: “Nisei” Stewardesses and Pan American World Airways (Durham, 2011), p.71. [↩]

- Kelsky, Women on the Verge, p.3. [↩]

- Ibid, p.4. [↩]

- Ibid, p.202. [↩]

- Yano, ‘”Flying Geisha”‘, p.93. [↩]

- Kelsky, Women on the Verge, p.202. [↩]

- Digital Public Library of America, “Shrinking the World: Pan American Airways in the Postwar Era”, Accessed at: https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/aviation (accessed: 16/01/2024 [↩]

- Quote from Yano, Airborne Dreams, p.57. [↩]

- Yano, Airborne Dreams, p.62. [↩]

- Quote from Yano, Airborne Dreams, p.63. [↩]

- Ibid, p.64. [↩]

- Yano, Modern Girls on the go, p.87 [↩]