Manchukuo, a puppet state that existed from 1931-1945 is often misrepresented or misunderstood by mainstream media as being a state of repression and a showcase of Japanese imperialism to repress Chinese nationalism and Japanise it.1 However, in reality, Manchukuo is unique in the field of spatial history as it showcases Japanese ambitions to combine multiple cultural styles and modern techniques to turn it into a ‘utopia’, making it even more advanced than the Japanese home islands itself and what it managed to achieve during wartime makes it even more remarkable. This blog will analyse a primary source of a tourist pamphlet then tie it to the wider theme of the Japanese vision of a multicultural utopia and how it aims to achieve it.

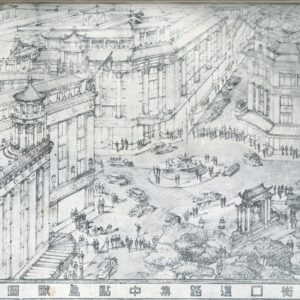

Figure 1: Japanese tourist pamphlet showcasing attractions of Liaoyang, Harbin and Fengtian (present-day Shenyang) extracted from: http://kousin242.sakura.ne.jp/wordpress014/%E6%88%A6%E4%BA%89%E3%83%BB%E8%B2%A0%E3%81%AE%E9%81%BA%E7%94%A3/%E6%98%A0%E5%83%8F%E8%B3%87%E6%96%99%E3%81%AE%E8%AA%AD%E3%81%BF%E6%96%B9/3785-2/

Description/rough translation:

This source is a tourist pamphlet produced in the 1930s by the Japanese-owned South Manchurian Railway Company with added annotations from the blog’s author. From the far left the large captions it translates to a starter guide of travels to Manchuria and it showcases an ancient pagoda in Liaoyang, a city not far from Shenyang. In the middle, we can see the Cyrillic script of Harbin and the Japanese hiragana which translates to: Tourism in Harbin. The interesting thing to note is that usually, foreign locations excluding China and Korea are usually written in the Katakana script but Harbin, a city with a Chinese name is written out in Hiragana, which implies the multicultural nature of the city. On the right, the pamphlet shows the old city gate of Fengtian, the name of Shenyang at the time, which showcases the rich Chinese cultural heritage of the city.

Inferences/Analysis:

In relation to the source above, the Japanese prioritised the needs of the Japanese citizens and realised the necessity of making Manchukuo as Japanese as possible to ensure permanent settlement to create a settler colony to alleviate the Japanese overpopulation of the home islands.2 However, given Manchuria’s already-present diverse population, the need for labour and the threat of possible Chinese and Soviet attacks from Manchukuo’s borders, and the international isolation Japan faced after its invasion of Manchuria, it aims to cultivate an image of racial harmony through its use of space.3 In order to make Manchukuo ‘Japanese’, the Japanese embarked on ambitious plans to create walled villages populated with men acting as both farmers and part-time soldiers, incorporating modern techniques such as wide streets and rows of housing organised in a hexagonal structures. This proved to be overly-ambitious as the Japanese did not have enough Japanese immigrants that moved to Manchukuo and that not all parts of Manchukuo were fertile as some parts were mountainous and not suitable for Japanese settlement due to climate differences. The cities that were populated by Japanese were mainly the cities close to the South Manchurian Railway like Dalian and Fengtian.

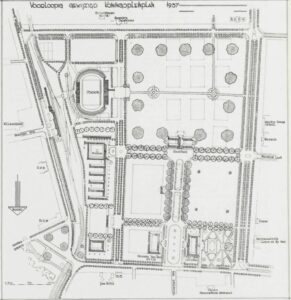

In relation to the picture however, the Japanese are using the cultures of Manchuria to promote tourism to justify its own expansionism and that former sites of cultural importance to those ethnic groups are reduced to mere tourist sites for Japanese to see how ‘exotic’ life in Manchuria is. By producing it for Japanese residents, the Japanese imperialists or the army aimed to draw support from the local Japanese populace to attract them to eventually settle into Manchukuo. In addition, the Japanese is also trying to use Manchukuo as a testing ground to test out their new city-planning techniques such as the incorporation of Chinese roofing techniques and Russian equipment like pechkas (Russian ovens) into Japanese-styled houses as Manchukuo is relatively undeveloped and much larger compared to the already-established colonies of Taiwan and Korea.4 Manchukuo attracted the attention of many famous Japanese architects and even world-renowned foreign architects like Le Corbusier that aimed to construct modern cities with public transport, hotel, amenities, religious spaces and green spaces while making sure residents have access to proper housing. This demonstrates how this often-overlooked aspect of empire building is multifaceted and that imperial urban constructions and utopia is an important pillar of empire building.

- Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, Twentieth Century Japan (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 1999), “Brave New Empire: Utopian Vision and the Intelligentsia” 241-268. [↩]

- Tucker, David, “City Planning without Cities: Order and Chaos in Utopian Manchukuo” [↩]

- Buck, David D., Railway City and National capital: Two faces of the modern capital in Changchun [↩]

- Sewell, Bill, Constructing Empire: Japanese in Changchun, 1905-45 [↩]