The 1930s saw a push by the Dutch colonial government of Indonesia to “modernise” the the country’s urban spaces. In 1934 a Town Planning Commission was established with the aim of developing urban planning regulations and guiding redevelopment. It presented its findings in 1938, advocating for the replacement of ad hoc urban development with a more centralised, methodological approach. They felt this would produce “harmonious” towns which would surely become reflected in the character of its inhabitants.1

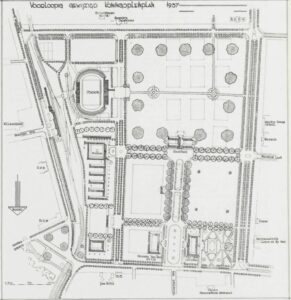

Source: IBT Locale Techniek (1937: p. 161)2

This 1937 plan for renovation to the Koningsplein, modern day Merdeka Square in central Jakarta, can be seen as symptomatic of the new philosophies of city planning sweeping Dutch Indonesia during this period. The plans centre on the town hall, placed amongst open green squares, at the junction of two boulevards. A stadium is situated in the south-east quadrant of the square and other notable buildings are visible along the edges, such as the Java Hotel and the Governor General’s palace.

One aspect of this plan which is immediately obvious is the desired beautification of the Koningsplein. The tree-lined avenues and inclusion of an intricate gardens in the north-western section of the square attest to the fact that this space was intended to inspire appreciation for the natural. Thomas Karsten, a prominent urban planner at the time, advocated for the inclusion of nature within the city, as long as it was carefully zoned and remained within its bounds.3

Colombijn and Cote argue that the reason for this attention to natural beauty is that urban beauty was intrinsically linked with the quest for order and control in colonial spaces.4 Order and organisation were seen as beautiful and beauty was believed to engender civility among citizens. The embodiment of this philosophy in the Koningsplein plan can be seen in the manicured lawns and geometrically divided sectors of the square. Ordered natural beauty within the square was intended to inspire an ordered society around it.

This approach to city planning echoes the City Beautiful movement, a philosophy which came to prominence in North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although the application of the City Beautiful movement necessarily differed by context, Peter Hall argues that its core tenant was the use of architecture and planning as theatre. As part of this movement, investment in urban beautification became a way to signal different values to a cities inhabitants and influence them in a positive fashion.5

The influence of the City Beautiful movement can be seen here, not only with the structured nature of the square, but also in the intended grandeur of the Town Hall and the Stadium. By placing these buildings in the middle of the square, surrounded by open space, they become the focal points of the space. Thus, the plan attempts to inspire respect and admiration for these symbols of Dutch government and modernity and, by extension, legitimise the colonial government.

Due to the Japanese invasion of Indonesia and the advent of World War II, these plans, along with many others, were never enacted . After the conclusion of the war and the Indonesian Independence movement, the Koningsplein was renamed Merdan Merdeka, or “Independence Square”. It was then redesigned and now consists of four diagonal streets radiating out from a new central National Monument.

The history of Merdeka Square and the Koningsplein is an interesting study in the shifting values of urban spaces. Once a key symbol of colonial aspirations for “modernisation” and order, it has since transformed into one of the country’s most visible monuments to independence. However, it has remained a tool of the government throughout, a way for regimes to articulate their priorities and values to the masses. As such, though the specific values it transmits may have shifted, it can be seen to still embody the early 20th century philosophies of urban planning as theatre.

- Pauline van Roosmalen, ‘Netherlands Indies Town Planning: An Agent of Modernization (1905-1957)’ in Cars, Conduits, and Kampongs, eds. Freek Colombijn and Joost Cote (Boston, 2015), p. 98. [↩]

- view (colonialarchitecture.eu) [↩]

- Freek Colombijn and Joost Cote, ‘Modernization of the Indonesian City, 1920-1960’ in Cars, Conduits, and Kampongs, eds. Freek Colombijn and Joost Cote (Boston, 2015), p. 3. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Peter Hall, Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design since 1880 (2014), p. 236. [↩]