‘People’s Communes’, or ‘人民公社’ were one of the key elements of the ill-fated Chinese Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Alongside the ‘Four Pests Campaign’ (除四害) and the ‘Backyard Furnaces’ (土法炼钢), the People’s Communes are one of the most well known aspects of the Great Leap Forward. An ambitious project of collectivization, it consisted of combining small agricultural communities into communes, eradicating private ownership and basing life around communal facilities and work. While the economic failings of the People Communes – both in their theory and practice – are well understood, one the most interesting, yet understudied elements of these Communes are their spatial dynamics.

Using a small sample of contemporary posters based around the subject, I want to explore two key themes that seem to be common in the presented spatial dynamics of the People’s Communes.

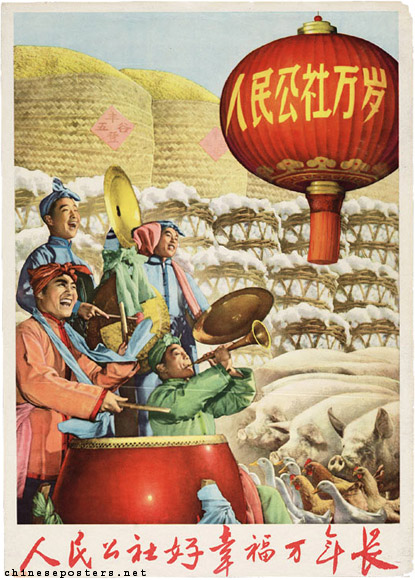

The first theme – one that is overwhelmingly present in nearly every propaganda poster relevant to the People’s Communes – is that of material plenty, of bountiful harvests and overflowing stores of foodstuffs. This theme is evident even in posters that are disconnected from agricultural topics. For example, the poster ‘When the dining hall is well-run, the production spirit will increase’ designed by Hu Yuelong, which focuses on the communal dining halls of the People’s Communes, features a large platter of food being brought to the already eating denizens of the hall.[1] However the poster which emphasizes this aspect of the People’s Communes the most is ‘The people’s commune is good, happiness will last for ten thousand years’, created by an unknown designer.[2] While the band of people takes prominence in the foreground of the image, they are physically dwarfed by agricultural produce, which dominates the background of the poster.[3] Huge, overflowing baskets of wheat and wool tower towards the sky, while the ground itself is obscured by a swarm of pigs and chickens.[4] The image’s sense of perspective also gives the sensation of the barrels continuing beyond the confines of the poster – creating an overall impression of boundless plenty, of an environment that can provide the many with even more.[5]

‘The people’s commune is good, happiness will last for ten thousand years’

‘When the dining hall is well-run, the production spirit will increase’

The second theme is that of generational harmony and cooperation – of the old and the young living and working together in harmony. This is a slightly more subtle theme, rarely if ever the primary point of the singular poster, but is near ever present, a consistent element throughout many of the posters. Hu Yuelong’s ‘When the dining hall is well-run, the production spirit will increase’ once again provides an example – with young children in the background, an older man in the middle ground, and a young adult woman in the foreground of the image.[6] Of particular note is the older man and the young adult woman, who appear to be both workers in the dining hall, with the older man carrying food, and the young adult woman carrying a tea cloth – creating an impression of the generations working, eating and living together.[7] The poster ‘The future of the rural village’ created by Zhang Yuqing provides another example of this theme, showcasing a future where farmers work in tandem with mechanized equipment in a rural setting.[8] The image creates an impression of old and new working together in multiple ways – the first being the rural, almost traditional setting of the image, with rolling hills under blue skies – being populated by artifacts of modernity – an electrical pole, a telephone, and mechanized farming equipment.[9] Another way in which the image furthers this theme is in the clothing of the people depicted in the image. Their clothing is for the most part modern – with jeans, overalls, and patterned shirts being prominent – but stands in contrast with their hats, which appear to be more traditionally styled, resembling ‘dǒulì’ or ‘斗笠’ style hats.[10] Theme of harmony between generations is more esoteric in its presentation in ‘The future of the rural village’, but is still present, speaking more to concepts of older traditions and new innovations working harmony, while ‘When the dining hall is well-run, the production spirit will increase’ is more concerned with harmony across human generations.

‘The future of the rural village’

Obviously, it would be foolish to take the presented themes discussed here at face value – not only because it is just a small slice of the larger concept of the People’s Communes, but because the lived experience of these Communes differed tremendously from the ideas that drove them. Still, there is use in examining the presented spatial dynamics of them as it allows us to assemble a more complete image of the planning and mindset that informed the Great Leap Forward as a whole – something, that in my opinion, requires further investigation.

[1] Hu Yuelong. When the Dining Hall Is Well-Run, the Production Spirit Will Increase. December 1958. Print, 53×77 cm.

[2] Unknown. The People’s Commune Is Good, Happiness Will Last for Ten Thousand Years. 1960. Print, 75×54 cm.

[3] Unknown. The People’s Commune Is Good, Happiness Will Last for Ten Thousand Years.

[4] Unknown. The People’s Commune Is Good, Happiness Will Last for Ten Thousand Years.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Hu Yuelong. When the Dining Hall Is Well-Run, the Production Spirit Will Increase.

[7] Hu Yuelong. When the Dining Hall Is Well-Run, the Production Spirit Will Increase.

[8] Zhang Yuqing. The Future of the Rural Village. April 1959. Print, 53.5×76.5 cm.

[9] Zhang Yuqing. The Future of the Rural Village.

[10] Ibid.