Hong Kong stands alongside Singapore, Bombay and New Delhi as being one of the most well known and defining spaces of the British colonial enterprise in Asia. But unlike the aforementioned cities, Hong Kong is unique in its relatively late date of colonization, being ceded to the British in 1841. This places the city in a rather unique period in terms of British colonial urban planning – the ‘Grand Model’ that had dominated the approach to colonial urban planning was reaching the end of its over two centuries long tenure.[1] Towards the end of the 1840s, arguments that favored a hands off laissez faire approach to urban planning would prevail, and remain dominant going into the tumultuous 20th century.[2] In short, Hong Kong represents a unique opportunity to evaluate the principles and practice of the ‘Grand Modell’ at its most developed point – and while the Australian city of Adelaide can provide a similar example,[3] the character of the British colonial project in Australia is sufficiently different to warrant another example. Where in the British colonial projects in places like India and China had relatively powerful and well organized local communities and governments that they were forced to engage with in some way, the Indigenous communities of Australia were systematically excluded and in many cases destroyed.

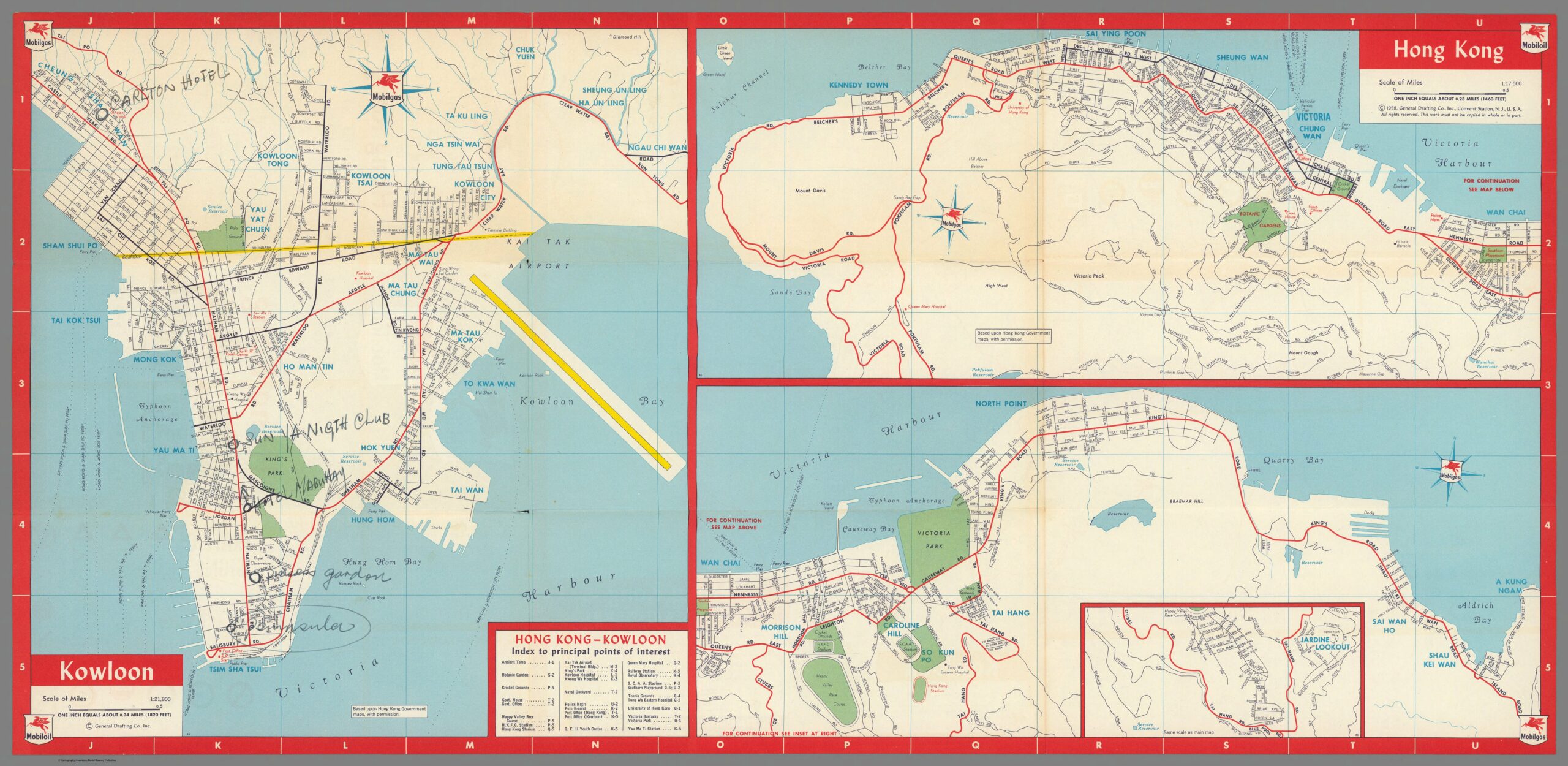

To aid this analysis, a map of Hong Kong from 1958 produced for the American Mobilgas company[4] will be used. The reasoning for the use of this particular map is twofold. Firstly, being produced in the late 1950s, the urban environment of Hong Kong has had time to develop, but the pressures of the World Wars and Great Depression would have made the prospect of any new urban designs at best difficult to implement. Secondly, the map being of an American origin lends it an advantage – while it is obviously far from an extremely accurate, unbiased presentation of Hong Kong, it is disconnected from the immediate context of the British and the systems of British colonial administration. It also clearly has a utilitarian purpose, most likely being used by tourists – meaning it is less likely to be a rendition of how Hong Kong ‘should be’ – at least from an urban planning perspective. One important limiting factor that should be mentioned is that the map only covers a small space of Hong Kong – mostly the areas enclosing Hong Kong bay, while the New Territories, Sai Kung, a significant portion of Hong Kong Island and Kowloon have been excluded from the map. The map is also not suitable for discussing the third and fourth principles of the Grand Model that Robert Home describes – we cannot use a map intended for consumption by tourists to give us an insight into whether or not Hong Kong was laid out in advance, nor can we use it to determine the exact size of the many main roads marked on the map[5].

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~299701~90070709:Kowloon–Hong-Kong-

The first principle of the Grand Model as defined by Robert Home is ‘deliberate’ urbanization – in short, strong central authorities prominent throughout or dominating the urban landscape.[6] This principle is displayed in the Mobilgas map of Hong Kong, especially on Hong Kong Island itself – the organs of the colonial administration (government offices, post office, police headquarters, barracks) are clustered around two major roads, Queen’s Road East and Queen’s Road Central, while roughly lying in the center of the urban build up on Hong Kong Island.[7] They also sit in close proximity to the ferry piers that are essential for travel between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon.[8] It should be mentioned however that this principle does not appear to be as strongly applied to Kowloon – while there is a post office and railway station sitting at the south end of the central Nathan Road, there is little else in the way of administrative organs or buildings symbolic of the British colonial administration on the mainland – something that seems strange at face value given the seemingly larger scale of the urban environment in Kowloon.[9] In short, the principle of deliberate urbanization in Hong Kong has been partially followed.

The second principle defined by Robert Home is that of land rights allocated in clearly differentiated regions of town, suburban, and country lots, something that Home describes as being definitively tied into the program of deliberate urbanization.[10] Where the previous principle is displayed in the 1958 urban landscape of Hong Kong, this principle is completely absent. Hong Kong, as displayed in this map, is a nearly totally urban environment, with the few suburban locations having no distinct boundary between themselves and the urban, and the country being not present at all.[11] The majority of the northern Hong Kong Island displayed on this map is an almost uninterrupted urban sprawl following tightly along the coast line, running from Kennedy Town to North Point, only interrupted by Victoria Barracks and the naval dockyard.[12] The inset displaying Jardine Lookout has an identifiable suburban structure with small winding avenues and roads, but is directly connected to the bustling urban environment north of it by the Happy Valley Race Course and Stubbs Road[13]. The layout of Hong Kong Island appears to have more in common with the concept of a treaty port and opposed to a colonial township. Meanwhile, the section of Kowloon displayed on this map is a wall of urban space that seemingly sheers off straight into nothing north of Clear Water Bay Road, Tai Po Road, Kowloon Tong and Kowloon Tsai.[14] It is worth mentioning that the limitations of the Mobilgas map as a source are apparent in this discussion – as mentioned before, it only covers a small region of Hong Kong, leaving out for example, the fishing villages of Sai Kung, and the expanse of the New Territories. Its purpose as a guide for American tourists may also be a limiting factor – with most of the interest of the map on the urban spaces of Hong Kong, the mapmakers may have simply not bothered to describe in detail the non-urban spaces of Hong Kong. However, even with those caveats in mind, it is reasonable to conclude that there is at the very least a lack of a consideration for the principle of differentiated regions of urban, suburban and country displayed in Hong Kong. This discussion also ties into the eight principles discussed by Robert Home, being that of a clear green space separating the town and the country – for the reasons already discussed above, it is fair to conclude that this principle was also at the very least disregarded.[15]

The fifth, sixth, and seventh principles laid out my Robert Home – respectively, that of a rectangular, grid based plot layout, the presence of public squares, and the reservation of plots for public purposes[16] can also be discussed in sum, as they are intertwined with each other due to the condensed nature of Hong Kong’s urban environment. To start, Hong Kong does display a rectangular grid layout, but not a standardized one.[17] While Hong Kong’s plots are nearly rectangular across the board, all flowing from a main road, they are not standardized, with many subsections of the urban space having different orientations and sizes for their plots – compare, for example, the rectangular layouts flowing out from the nearly parallel Nathan Road and Ma Tau Wei Road in Kowloon[18]. These layouts are also interrupted at several points by public places – typically gardens, that seem to be centrally located ala a public square[19]. For example, Southorn Playground in Wan Chai lies at the center of the urban space surrounding Hennessy Road, but in doing so interrupts the standardized grid plots surrounding Hennessy Road and Queen’s Road East.[20] A more prominent example is that of King’s Park, lying at the center of Kowloon – King’s Park does not conform to any kind of grid layout, and indeed represents a significant break from the sprawling grid layout to its east, west and south.[21] Taken in sum, I argue this represents an adherence to the spirit of the relevant principles, but does not follow them strictly to the letter. The grandeur and symbolism of a public square at the center of the city is not present, instead with public parks taking their place – spaces of leisure but still symbolic – the name ‘King’s Park’ is in itself symbolic, especially considering it is in the center of the Kowloon urban environment. A grid based layout is present, but its shape and form shifts across the landscape, serving more as a loose guide opposed to a strict commandment. The only principle of the three followed more closely the reservation of plots for public spaces – as some of the public spaces do roughly follow the grid based layout and ‘slot’ neatly in – although this is not universal, as discussed in the case of King’s Park.

To sum up, we can see a mixture of significant deviations from the principles of the Grand Model described by Robert Home in 1958 Hong Kong. There are a number of factors that could contribute to this that I can think of – the first and most obvious is the difficult nature of the landscape in Hong Kong, being a mixture of jungle, mountain and coast that would limit available space and require creative engineering solutions. Another possibility is that the focus of the British colonial project in Hong Kong was not on the land itself, but rather on the bay, harbor and infrastructure surrounding the harbor – this would change the spatial priorities of an urban planner, and perhaps bring Hong Kong closer in spirit to coastal Chinese treaty ports and their bunds, opposed to the settler colonization projects of Australia or Africa. Regardless, further investigation is warranted into the nature of British colonial urban planning – perhaps the Grand Model and its principles can be better thought of as a guideline opposed to a stricter set of rules.

[1] Home, Robert K. “The ‘Grand Modell’ of Colonial Settlement.” In Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities, Second Edition., 9–37. Planning History and Environment Series. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013. 9-10.

[2] Home, Robert K. “The ‘Grand Modell’ of Colonial Settlement.” 33.

[3] Ibid. 29-30.

[4] General Drafting Co. Inc. “Mobilgas Mobiloil Friendly Service Everywhere in Hong Kong.” Separate Map. Standard-Vacuum Oil Company, 1958. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

[5] Home, Robert K. “The ‘Grand Modell’ of Colonial Settlement.” 10-13.

[6] Ibid. 10-11.

[7] General Drafting Co. Inc. “Mobilgas Mobiloil Friendly Service Everywhere in Hong Kong.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Home, Robert K. “The ‘Grand Modell’ of Colonial Settlement.” 11-12.

[11] General Drafting Co. Inc. “Mobilgas Mobiloil Friendly Service Everywhere in Hong Kong.”

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Home, Robert K. “The ‘Grand Modell’ of Colonial Settlement.” 17-19.

[16] Ibid. 10.

[17] General Drafting Co. Inc. “Mobilgas Mobiloil Friendly Service Everywhere in Hong Kong.”

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.