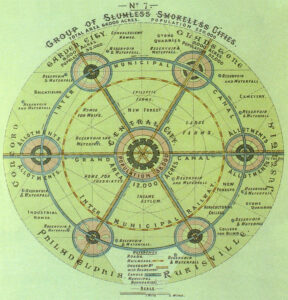

This blog post focuses on a diagram from Ebenezer Howard’s book, ‘To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform’. In this book Howard set out his vision for the Garden City, a form of settlement designed to combat the overcrowding, disease, and squalor in cities, but also to provide job opportunities and social life not seen in rural England.

This particular diagram shows Howard’s wider vision, where a central garden city was surrounded by smaller satellite cities, connected by a system of roads, railways, and canals. In addition, the two developments set aside for allotments would help provide for the overall city, in combination with farms situated between municipalities. The overall effect of the diagram was to set out a planned community which could sustain its population with both food and employment, while also remaining self-sufficient with its welfare programs. This differentiated it from later projects like the 1950s New Towns, which were orchestrated by centralised government.

The diagram also helps shed light on contemporary views surrounding urban social problems and providing care for people with illnesses considered uncurable. The diagram clearly shows that homes for orphans and alcoholics would be situated outside the city proper, alongside an insane asylum. This highlights the arms-length approach people held towards these issues at the turn of the century: even when sympathetic to reducing these social problems, the first impulse was to remove them from the more populated cities. However, this could also fit with ideas of rural air being beneficial to health. In this way, Howard’s plan would seek to utilise the benefits of the countryside while keeping able-bodied orphans and recovering alcoholics close to job opportunities and places of education.

Above all, this diagram is clearly only theoretical. The actual layout of the city is not shown, and the locations of the surrounding services are approximate at best. There is also no mention of the landscape the perfectly straight roads and perfectly flat canals would have to contend with. This was because of two reasons: the diagram is solely conceptual, but also there were no examples of such a city to work with at the time Howard published his book. In reality, the Garden City would struggle to grow due to a lack of funds, while existing roads and railways would limit the symmetry and cohesiveness of the eventual settlements that grew using this plan.

Overall, the diagram is a useful tool to visualise Howard’s broader idea of a self-sufficient settlement combining the town and country. The model of the Garden City would utilise the space and health benefits of the countryside, while retaining a large variety of job opportunities which had caused the mass migration into cities during the nineteenth century. This fulfilled one of Howard’s most important ideas, the town-city: a combination of the best of both living environments. While no full Garden City was ever made, Howard’s design shows how urban planners at the start of the twentieth century were increasingly focused on solving social and economic problems through planned city design.

Sources

Hall, P. 1990. Cities of Tomorrow. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 86-136.

Diagram – Hall, P. Cities of Tomorrow, p. 92.