The article entitled ‘Town Planning in British Malaya’ provides an insight into the unique challenges that faced town planners in their attempts to design new urban spaces in the colonies, particularly at a time when town planning was still considered a ‘tentative experiment’ and little legal and administrative frameworks existed to support it1. The author of the article is Charles Reade who was possibly the most active and influential figure of the first generation of town planners. Significantly he wrote this piece in 1921, at the very beginning of his appointment in the Federated States of Malaya, and published in the first, and seminal, international journal of town planning the Town Planning Review. This article then, acts as a very public documentation of an influential planner’s process.

Reade may have even fancied this article as the start of a guide to planning in the region. As Robert Home points out he did see himself as somewhat of a missionary: ‘There never was a time in the history of the whole [town planning} movement when the need for enlightened missionary effort throughout the civilised world was greater…’2. Born in New Zealand, Reade initially made an impact in town planning circles in New Zealand and Australia most notably in his design of an Adelaide suburb, the Colonel Light Gardens. However, political opposition to his methods led him to leave Australia in 1921, the year the article was written, and accept the position of Government town planner in the Federated States of Malaya. As tentatively optimistic as Reade presents his prospects in the colony, his strict approach would lead him to be manoeuvred out of power. He would then go on to work in North Rhodesia and South Africa before he tragically took his own life in Johannesburg.

As someone who was ‘endeavouring to apply strictly scientific, and consequently really practical methods’ to his planning, it is unsurprising that within this article he stresses the need for legislation, specifically shaped for the Colonial context: ‘Most important of all is the devising of legislation and machinery suited to the requirements of a British Protectorate or Federation of States largely peopled and worked by Malays, Chinese and various Indian Workers.’.3 As an early figure in town planning, little legislative and administrative provisions existed during Reade’s career. By 1921 two central acts existed. The first was the British Housing and Town Planning Act 1909 which most notably banned the practice of ‘back to back’ housing commonplace at the time and required that local authorities had to introduce systems of town planning.4

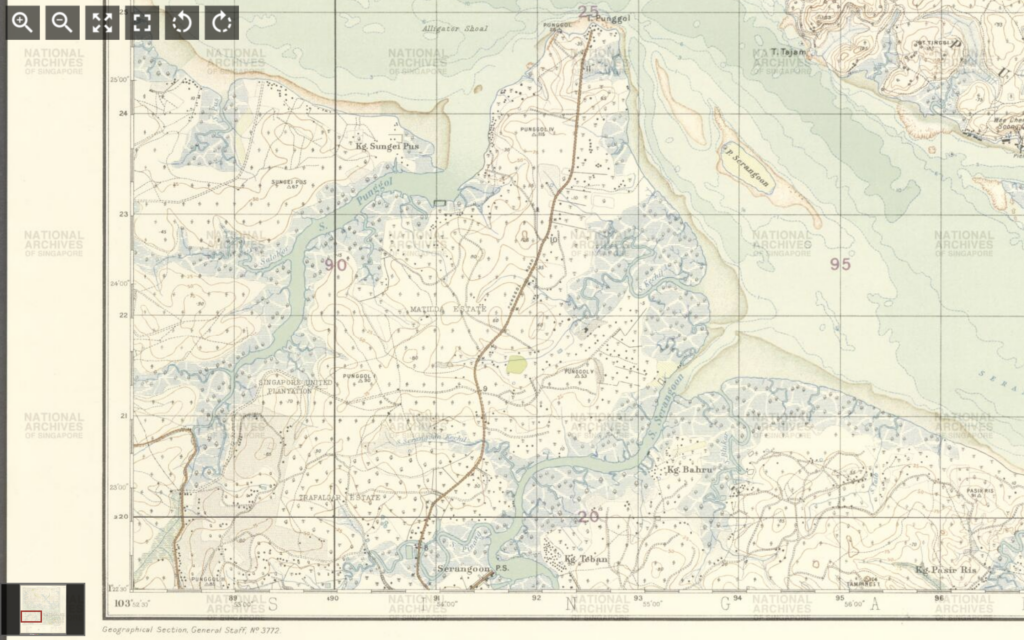

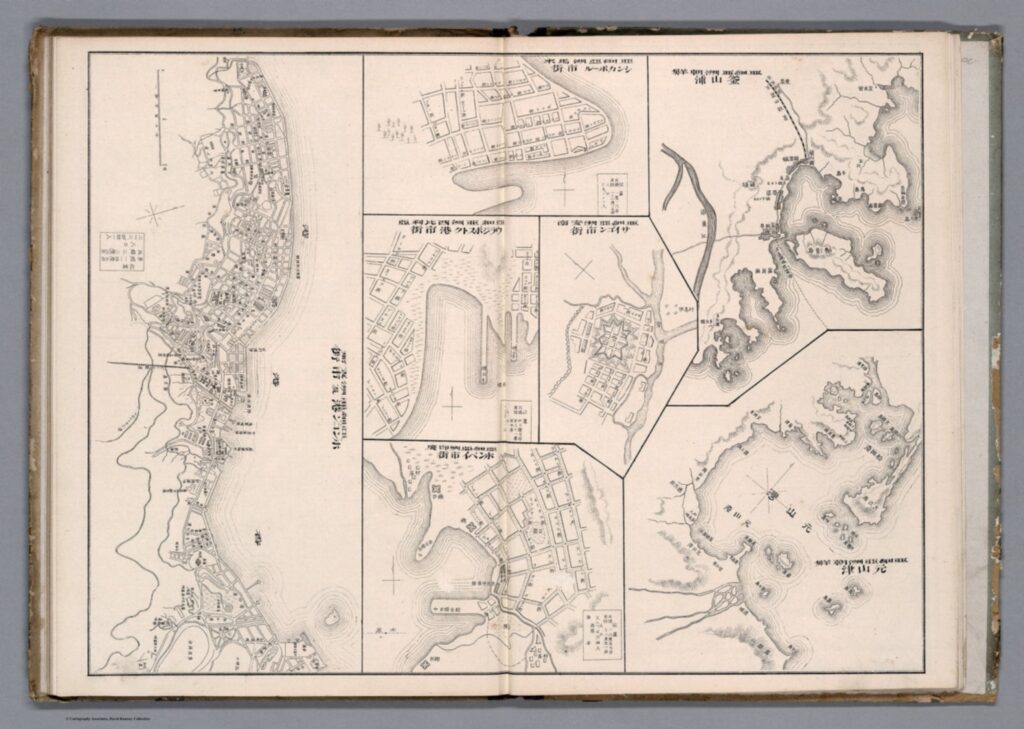

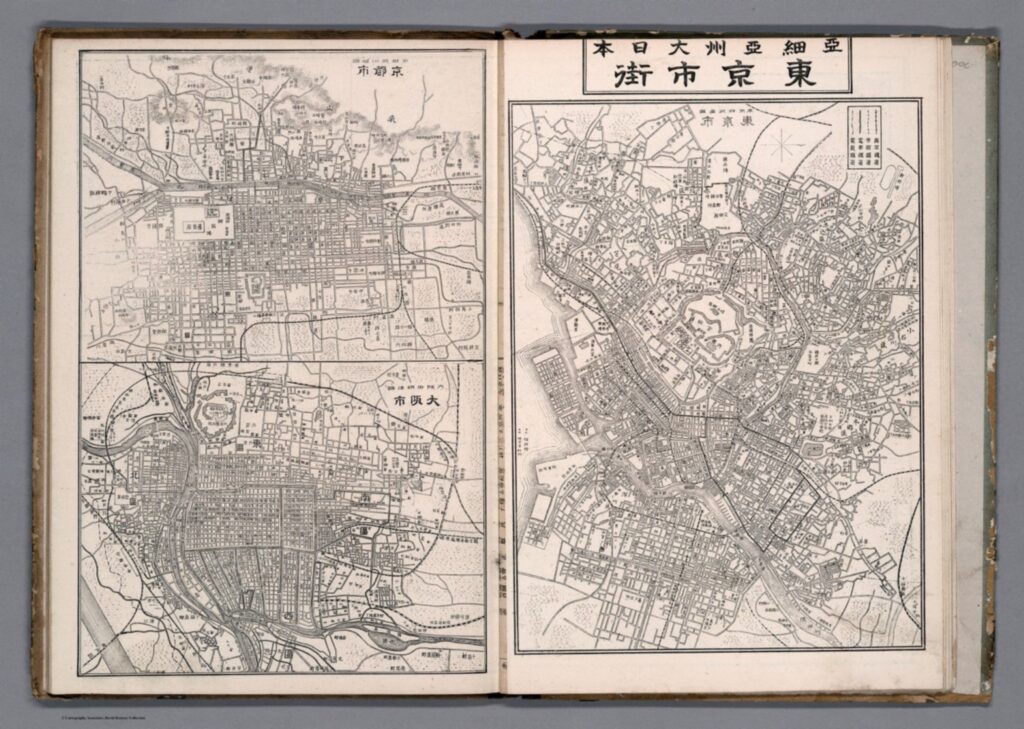

The second was the 1915 Bombay Town Planning Act, the first significant colonial town planning legislation. Building off of the 1909 Act, the 1915 legislation wanted to provide better financial provisions by the betterment levy and the integration of land pooling and redistribution practices. It is this very practice that leads Reade to invoke the Bombay Act in the article when he is describing the problem of awkwardly shaped holdings in ‘the East’ poses to those involved in the replanning process. The assumptive tone he uses when bringing up the act ‘Under the “Bombay Town Planning Act” city planners will know of the replanning schemes…’ implies that, given the international nature of the journal, this piece of legislation has already become a mainstay model in the global town planning discipline.5 Aside from these two acts, from 1917 in Malaya the provisions for town planning were largely confined to sanitary boards, which were primarily concerned with public health improvements (6). Reade acknowledges that these authorities have completed ‘much good work’ but finds an ‘inadequacy of existing powers and machinery when it comes to dealing with economic and administrative questions relating to resumption, methods of rating and valuation of land, also exchanges and redistribution of ownerships, etc’ (7).

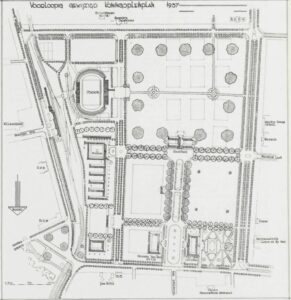

In answer to Reade’s frustration, in India, a proto-form of town planning was emerging through bodies called Improvement trusts. They primarily introduced procedures to clear slum neighbourhoods in cities. Below the plea for more legislation, Reade highlights the significance of the upcoming ordinance which will create the Singapore Improvement Trust (8). If Home is right that they acted as a form of pre-cursor to town planning legislation, and Bombay, with its influential planning act, was one of the earliest towns to have one in 1898, then we can understand why he views this as an important next step to secure more legislation (9). Certainly only 2 years after this article he introduced into Malaya the Town Planning Act of 1923 which brought together development, leasing land, town improvement and building regulations into one piece of legislation. Given that control of town planning in Malaya was reverted back to sanitary boards in 1927, one can’t draw a definite general timeline of town planning infrastructure from this example, however, it could potentially illustrate a common legislative trend in colonies.

Aside from legislative concerns, Reade spends much of the article outlining specific regional considerations he has to make before he can begin the project of town planning. Broadly these concerns fall under the category of inherited problems from rapid urban growth and colonial rule. One such issue is the industry of mining, which was central to the economy of the colony, In fact as early as 1891, a government newspaper stated that mining was successful enough to be independent from the aid of the state and that the country was dependent on its resources (10). Yet Reade bemoans its environmental impact, specifically the rising river levels, the flooding, and the influx of silt that has forced some towns to be abandoned (11). Given how spatially disruptive mining can be, it follows that town planners and commercial mining enterprises might have often been at odds. Indeed, later in Reade’s career, in Northern Rhodesia, he faced tension when a mining company and the colonial authorities clashed over the nature of the town planning, with the former wanting to quickly erect a company town and the latter wishing to keep governmental functions out of private hands (12). If Reade’s generation of planners found an under-implementation of their designs, much of that derived from the local opposition from settler and commercial interest groups (13).

Indeed, in this article what stands out as a major concern for Reade is negotiating the ideals of settlers during the replanning process. Reade explains that because of a common trend of awkwardly shaped holdings in Asia, a land pooling and redistribution system is necessary to allow the process of urban replanning to occur (14). However, despite its necessity, he worries that the implementation of such a strategy will be difficult due to the ideal of individualism held fiercely by Western settlers in the colonies. He indicates that even the temporary termination of individual ownership to create communal land could invoke an extreme response. He admits that without land pooling, he fears ‘that the big stride forward, so often desired, will still remain the merest shuffle in civic shoe leather.’ (15). And as Home asserts, this was the result of much of the first generation of planners’ efforts (16).

Overall, aside from legislative underdevelopment and local opposition, what this frank appraisal of the issues that faced Reade in Malaya reveals is twofold. Firstly, while the city planners were integrated into the colonial machinery, they were afforded enough separation to outline concerns about the colony – such as the rubber and tin industry being in a ‘slump’ and the existence of uncooperative settlers – in a public forum – the Town Planning Review – which many government employees weren’t afforded. Secondly, it is apparent that Reade, having spent most of his career managing largely settler populations in New Zealand and Australia, views the prospect of planning a city with an added racial consideration as a problem to negotiate rather than the opportunity that a planner like Patrick Geddes saw it for. He viewed land pooling and replanning subdivisions of land as particularly problematic because the majority of the landowners are Asiatic (17). Relatedly, earlier in the article he refers to ‘incidences of racial problems’ which he urges need to be ‘studied and clearly understood’ (18). While neither of these statements are expanded on, generally there appears, returning to the quote about legislation and machinery for ‘States largely peopled and worked by Malays, Chinese and various Indian Workers’, to be an anxiety that the tools and mechanisms of city planners and the state are not equipped to handle the governance of a multi-ethnic state and the challenges it poses (19). Given that two decades later the process of decolonisation in the British Empire began, this anxiety was not completely ill-founded.

(6) Home, Of Planting and Planning, p.182

(7) Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p.162

(8) Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p. 164

(9) Home, Of Planting and Planning, pp. 177-179

(10) ‘Notes – Planting’, The British North Borneo Herald and Monthly Record, (Sandakan, 1st of August, 1892), p.256

(11) Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p. 163

(12) Home, Of Planting and Planning, pp. 185-187

(13) Home, Of Planting and Planning, pp.149-176, specifically p.173-174

(14) Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p.165

(15) Ibid.

(16) Home, Of Planting and Planning, pp.149-176, specifically p.173-174

(17) Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p.162, 165

(18) Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p.162

(19) Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p.164

- 1931 Garden Cities and Town Planning article cited in Home, Robert K., Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities, (Taylor & Francis, 1996), p.173 [↩]

- Home, Of Planting and Planning, p. 165 [↩]

- Charles Reade cited in, Home, Of Planting and Planning, p. 167, Charles C. Reade, ‘Town Planning in British Malaya’, Town Planning Review, 9;3, (1921), pp. 162-165, p.164 [↩]

- ‘The Birth of Town Planning’, UK Government, accessed 2nd of October, 2023, The birth of town planning – UK Parliament [↩]

- Reade, ‘Town Planning’, p.165 [↩]