Badly Drawn Maps and what they can teach us

What makes a good historical map? Do detail and accuracy outweigh aesthetics and simplicity? Alternatively, what makes a bad historical map? Plenty of contemporary pop culture articles find entertainment in examining strange historical maps, assuming their scientific inaccuracy is something comical. But within these ‘inaccuracies,’ can we find historical insight we might have otherwise overlooked? This is the essential question Martin Bruckner seeks to answer. Don’t dismiss a historical map based on assumptions of what makes a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ map, argues Bruckner, rather we should explore why these definitions exist in the first place.

When examining maps, we make various assumptions about the relations of the map: the territory itself as existing independently of the map, north/south being top to bottom, east/west being right to left, and so on.[1] The “old” method of understanding historical maps, according to Bruckner, suggests that ‘good’ maps have unmistakable meanings, and ideals like truth and error are conceptually presented through them. They are the products of empirical science.[2] The map is a representation of a place. Yet, from the 1990s, ‘place’ began to be thought about more broadly, and scholars began treating maps as “subjective representations of social locations and human activities.”[3] This understanding also treats maps as places themselves.

“In this view, maps are considered text-specific locales, or sites, shaped by a variety of contexts, ranging from the biography of the mapmaker to the geography of map production to the language of maps.”[4]

For Bruckner, however, our analytic approach to maps should go a step further than this text-based understanding. Historical maps are representations of places deeply endowed with sociality, being both man-made and “man-used.”[5] He argues for considering maps as products of social practice, shaped by all of the aspects that go into their creation; they are moulded by the engraver, painter, ink and paper suppliers just as much as the scholars and librarians who consume them.[6] Similarly, Matt Reeck views maps as “architecture of mind”. He argues they are a dynamic component of a historical process of commerce and settlement: “The advent of good maps is the advent of control over the land…”[7] For Reeck, mobility and movement of peoples is directly connected to cartography, and yet maps too often seek to standardize this; they aspire to “place places outside of time.”[8] Maps are social constructions, they push political agendas and represent societal attitudes. Their creation is often greatly influenced by power interests completely outside of the cartographic industry. Thus, can historical maps truly be deemed either ‘good’ or ‘bad’?

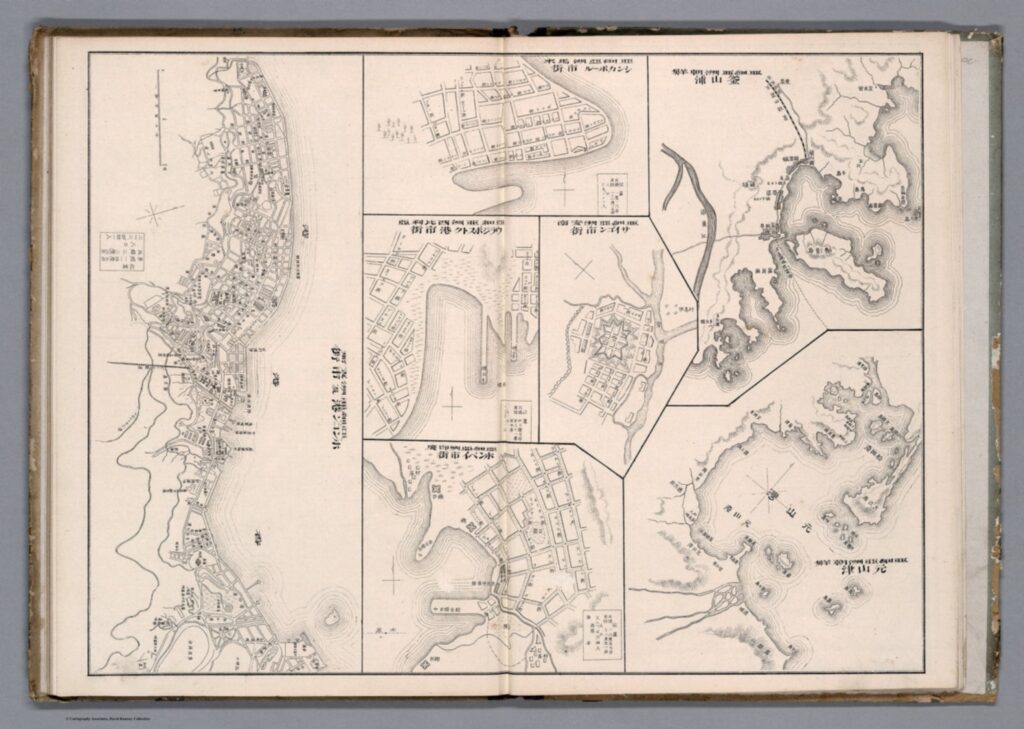

Taking Bruckner’s social approach, empirically ‘bad’ historical maps can now be considered useful and insightful in how they relate to issues other than physical geography. We can provide maps, seemingly objective creations, with historicity and time. Although developed in an American context, Bruckner’s approach can be equally applied to historical maps from East Asia. Examine this 1906 (Meiji 39) map by Japanese cartographer Yamane Akisato:

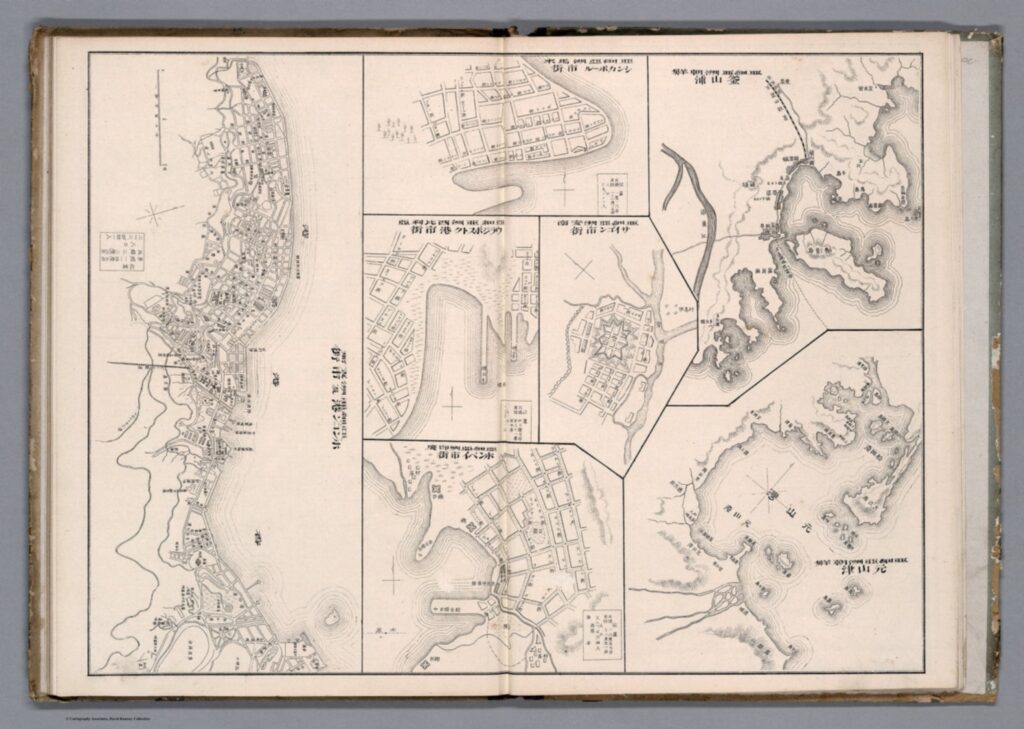

This atlas page shows 7 maps of various East Asian cities. Included (from left to right) are Hong Kong, Singapore, Vladivostok, Saigon, Bombay, Busan, and Wonsan. The maps show details of the city plan (roads, rivers, railways, etc.), the coastal outline, and major buildings, such as military stations. They are drawn in a simplistic black and white line drawing, which allows for a focus on the layout and structure of the cities and makes them easy to compare. These city maps were published in the atlas in between more detailed and coloured maps and illustrations, and the atlas includes text in both Japanese and Chinese. You may notice that these simple drawings are particularly ‘inaccurate’, or, in the very least, lacking detail. The coastline in the top-centre city (which I assume is meant to be Singapore, although it is difficult to tell) is comically simple, as if included in the compilation as an afterthought. In comparison, the coastlines of Busan and Wonsan on the right are drawn with more extreme detail. Deer Island in Busan’s Bay is especially noticeable, and details of smaller islands and water depth is even included. Although the map of Hong Kong (located far left) is denser, several of the streets are mislabelled in comparison to the reality of their positionality to one another. This strange picking-and-choosing of what details to include and what details to leave out by Akisato, the cartographer, is what makes this map so fascinating. If we now apply Bruckner’s social approach to analysing this map, it opens up the potential for historical interpretation and insight to be gained from it.

Drawn from the Japanese perspective in 1906 (Meiji 39), the map tells us how Japanese citizens might have seen and understood the world, and the importance of other cities in East Asia in comparison to their own. Placing these maps within the historical context of Japan’s activities in 1906, it makes sense for the map of Busan to detail so clearly the coastline and water depth around the city. Busan was a treaty-port which the Japanese held particular influence over around the time this map was published, and in which a strong Japanese presence had existed since the 15th century. Busan was the foothold through which Japanese forces established their control over the Korean peninsula prior to annexation in 1910.[9] It is likely Akisato may have visited Busan directly during his life, although not much is known about the cartographer himself and this is merely hypothetical. Regardless, as a Japanese citizen Akisato would have had, at the very least, more readily available access to information about Busan than to information about Singapore, for example, which was under British colonial control at the time.

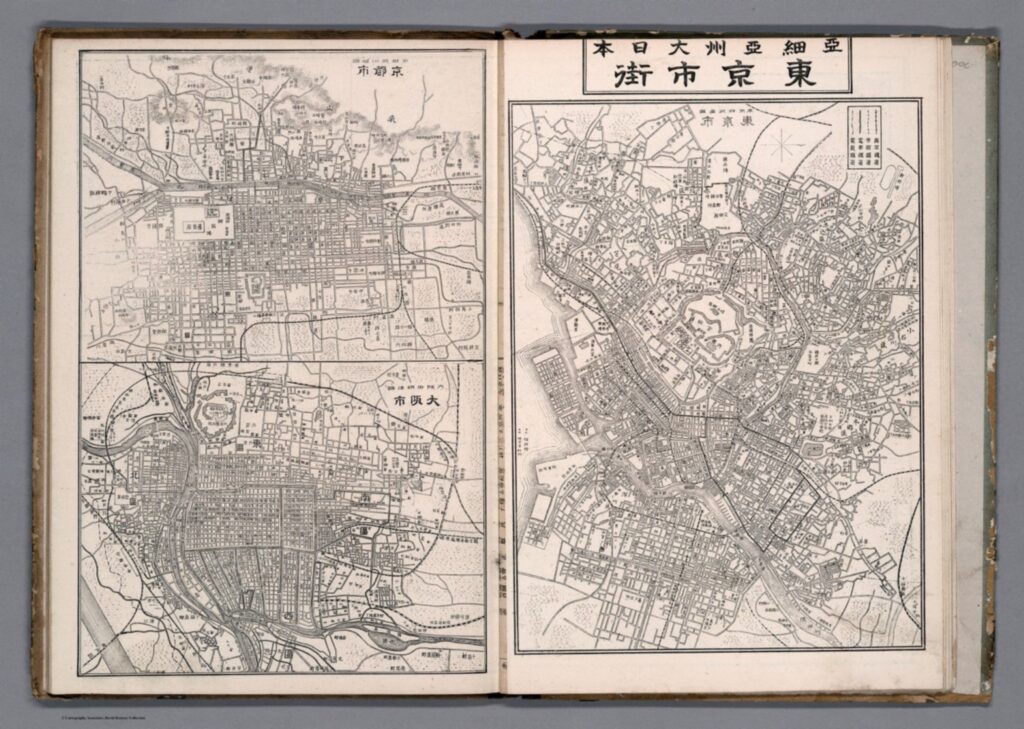

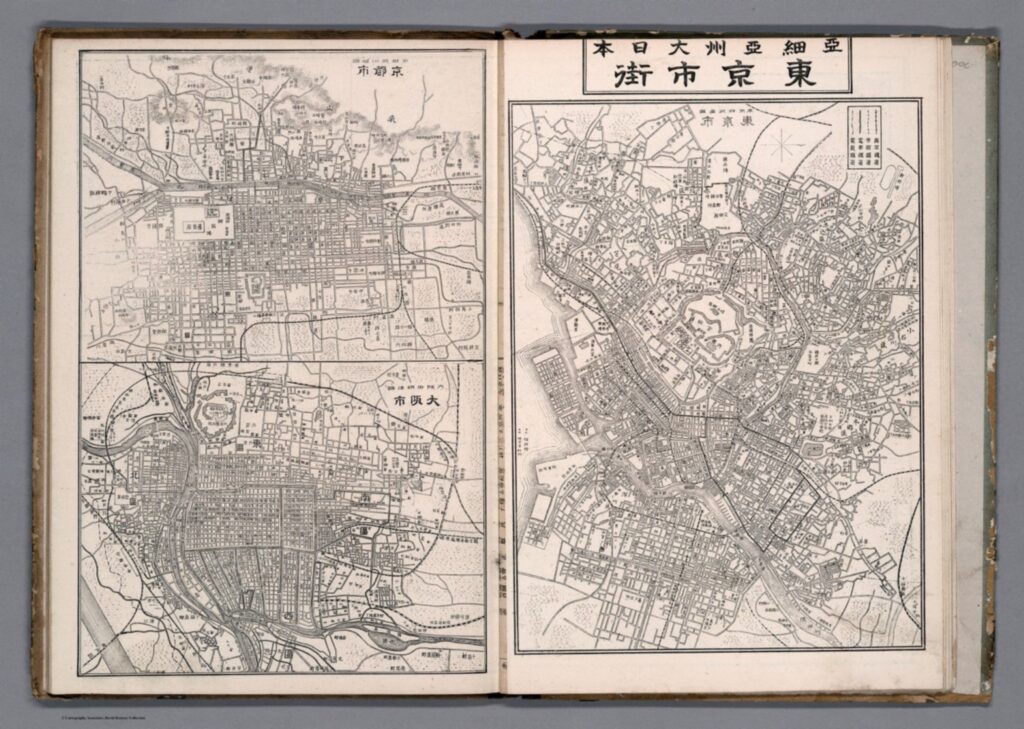

More acutely, these maps tell us how Akisato thought these cities should be presented in his atlas, and thus to those learning from his atlas. This highlights what he might have thought relevant, or in this case, not relevant, to be teaching other Japanese consumers about the wider world and about other cities across Asia, especially in comparison to Japan’s own major cities. There is a similar insert page in the same atlas that depicts Tokyo and its surrounding areas, Kyoto, and Osaka. These maps, meant to act as educational tools in the same way as the first 7 we examined above, are extremely dense, showing the grid block layouts of these cities in exact detail.

Considering the Japanese colonial context under which these maps were created once again, we can invoke Bruckner’s social approach to understand why these Japanese cities are presented more carefully. In the book How to Lie with Maps, Mark Monmonier argues that nations often enhance map features that support their point of view on the world and leave out details on the features that sit contrary to this.[10] Is this what is occurring here with Akisato’s atlas? Potentially, but further insight into this would require more research on his career and the publishing details of the atlas itself. At any rate, these maps are shaped deeply by Japanese colonialism and the power relations at play in East Asia in the early 1900s.

J. B. Harley maintains that historians of cartography often simply accept the cartographer’s suggestions of what historical maps are meant to represent, and advocates for greater scrutinization of maps as forms of knowledge creation. [11] The relationship between representation and reality contained within maps affects our relations to and perceptions of the material world, which is all the more pertinent considering a historical context far prior to the information technology era. These historical Japanese maps of various East Asian cities provide a good example of how we can scrutinize as Harley suggests, and they offer a great entry point for further research in this area.

[1] Searle, John. R., ‘Chapter 4: The Map and the Territory,’ in Wuppuluri, S. & Doria, F. A. (eds.) The Map and the Territory, Springer International Publishing (2018): p. 72

[2] Bruckner, Martin, ‘Good Maps, Bad Maps; or, How to Interpret A Map of Pennsylvania,’ Pennsylvania Legacies, Vol. 9, No. 2 (November 2009): p. 40

[3] Ibid, p. 40

[4] Ibid, p. 40

[5] Ibid, p. 40

[6] Ibid, p. 41

[7] Reeck, Matt, ‘A Brief History of the Colonial Map in India – or, the Map as Architecture of Mind,’ Conjunctions, No. 68, Inside Out: Architectures of Experience (2017): p. 185

[8] Ibid, p. 185

[9] Kang, Sungwoo, ‘Colonising the Port City Pusan in Korea: A Study of the Process of Japanese Domination in the Urban Space of Pusan During the Open-Port Period (1876-1910)’, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Oxford (2012): p. 86

[10] Monmonier, Mark S., How to Lie with Maps, 3rd ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2018): p. 132

[11] Harley, J. B., ‘Deconstructing the map,’ Passages, University of Michigan Library https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/passages/4761530.0003.008/–deconstructing-the-map?rgn=main;view=fulltext [Accessed 09/10/21]

Primary Sources:

Akisato, Yamane, “Buson, Wonson, Vladivostok, Saigon, Bombay, Hong Kong.” from New Atlas & Geography Table (Bankoku chin chizu chiri tokeihyo), Nakamura: Shobido, Meiji 39 (1906) https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~313791~90082699:Buson–Wonson–Vladivostok–Saigon-?sort=Pub_List_No_InitialSort&qvq=q:vladivostok;sort:Pub_List_No_InitialSort;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=11&trs=12# [Accessed 08/10/21]

Akisato, Yamane, “Tokyo and environs, Kyoto, Osaka.” from New Atlas & Geography Table (Bankoku chin chizu chiri tokeihyo), Nakamura: Shobido, Meiji 39 (1906) https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~313790~90082700:Tokyo-and-environs–Kyoto–Osaka?sort=Pub_List_No_InitialSort&qvq=q:author%3D%22Akisato%2C%20Yamane%22;sort:Pub_List_No_InitialSort;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=21&trs=36 [Accessed 10/10/21]

[3]

[3]