Gyeongbok Palace was originally built in the 14th century as the centre of Joseon Dynastic rule in Seoul, Korea. The first king of Joseon constructed the palace as both physically and symbolically representative of the auspiciousness of his rule. This, in turn, bolstered the legitimacy of the dynastic change and helped to naturalise the movement of the capital from Kaesong to Seoul.[1] This process was deeply influenced by concepts of pungsu, or ‘geomancy’ in English; “traditional ideas and practices concerning the relationship of human beings with the surrounding environment.”[2] Geomantic ideals were utilised in order to emphasise the good geographic placement of Gyeongbok Palace and of the surrounding landscape to the people, which helped the ruling elites to solidify their power. Following the annexation of Korea in 1910, the Japanese defaced the Gyeongbok Palace site in an attempt to accentuate their own power and naturalise the authority of their colonial rule. Most importantly, they manipulated Korean geomantic ideals to reinforce this, and constructed their General Government Building on the palace grounds.[3] How they engaged in this ‘geomantic warfare’ is what I will explore in this post, making use of historical photographs to do so.

“The Japanese colonial government carefully examined the geomantically auspicious sites of Korea, and then ruined and occupied the sites by replacing Korean buildings with Shinto shrines or Japanese government buildings.”[4]

In The Culture of Fengshui in Korea, author Hong-Key Yoon employs the cultural-geographic approach of “reading landscape as a text like a book” to analyse the site of Gyeongbok Palace.[5] Yoon writes about the changes to this cultural site across the 20th century, and examines how ideologies and power relations were built into the meanings taken from these physical geographic changes. Geomantic interpretations were central to this, and Yoon argues these social constructions were used to artificially reinforce popular beliefs about specific landscapes.[6]

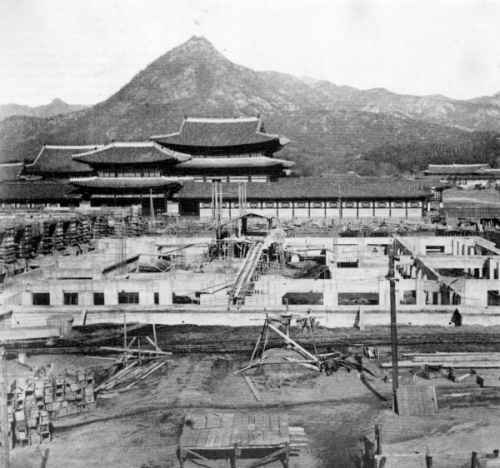

Archival photograph showing the construction of the Japanese General Government Building in front of Gyeongbok Palace.[7]

The Japanese General Government Building in Seoul was built in 1926 by the Empire of Japan as the central administrative headquarters of their colonial rule over Korea. The building was constructed over the site of Gyeongbok Palace, widely renowned as one of Korea’s most auspicious and important cultural locations. Yoon explains how the Japanese used a method known as ‘palimpsest’ in order to naturalise their new colonial icons. This involves a deliberate comparison of a new “strong” icon against an old “weak” icon.[8] In the case of the Gyeongbok site, the Japanese did not completely replace the Palace with their own building.[9] Rather, they left part of the ruins in place to the back of their new building (an area which, according to geomantic interpretations, is unfavourable). The General Government Building towered over the Palace in both physical height and symbolic strength. This deliberate visual comparison of the two powers represented here had a clear interpretation: Japan was strong, Korea was weak.

Archival photograph of the former Japanese General Government building located in front of Gyeongbokgung Palace in central Seoul (source: Busan Museum).[10]

The Japanese were said to have deliberately disrupted the geomancy of the Korean site in an attempt to legitimize their power and de-legitimize Korean nationalism. During the debate in the 1990s over whether the General Government Building should be demolished, there was a widespread public discourse that the building had been the leading weapon in a Japanese plot to deliberately block Korea’s national energy (as encapsulated in the Gyeongbok site).[11] This was proliferated by the discovery of “Japanese spikes” under the site of the building during the demolition process;

“These spikes were 20 to 25 centimetres in diameter and 4 to 8 metres in height, and they were tightly packed, about 60 centimetres apart from each other. (Dong-a Newspaper, 29 November 1996).”[12]

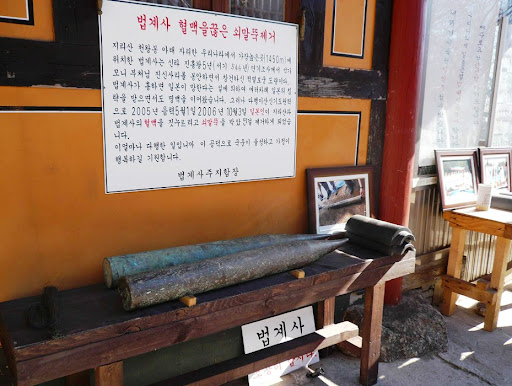

A photographic example of similar Japanese spikes supposedly found by activists between 1995 and 2001 in the Jirisan National Park.[13]

The spikes were driven into the ground supposedly as part of the building’s foundations but, in the mind of the Korean public, they were a purposeful attempt to suppress the “earth-energy” of Joseon’s finest palace.[14] Without the nationalistic geomantic interpretation of what these spikes represented, their findings would have otherwise been of little note to the Korean public. Although, it is important to note that whilst the argument that the Japanese purposefully constructed their General Government building in order to destroy the geomancy of Gyeongbok palace is widely accepted, the argument that Imperial Japan deliberately fixed these iron spikes into the ground as part of this remains controversial.[15]

Yoon argues that geomancy was not the cause of this battle over the Gyeongbok landscape.[16] Rather, the geomantic interpretations taken from the actions of these two powers (and the buildings represented by them) were used and manipulated in order to achieve various political aims, and to legitimize and de-legitimize support for Imperial Japan in the Korean public mindset throughout the 20th century.

[1] Yoon, Hong-Key, ‘Ch15 Iconographic Warfare and the Geomantic Landscape of Seoul’, in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books (1988): p. 283

[2] Han, Jung-san, “Japan in the Public Culture of South Korea, 1945-2000s: The Making and Remaking of Colonial Sites and Memories,” Japan Focus, Vol. 12, Issue 15, No. 2 (2014)

[3] Yoon, Hong-Key, ‘Ch15 Iconographic Warfare and the Geomantic Landscape of Seoul’, in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books (1988): p. 277

[4] Ibid, p. 287

[5] Ibid, p. 304

[6] Yoon, Hong-Key, ‘Ch14 The Social Construction of Kaesong,’ in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books (1988): pp. 241-42

[7] Booth, Anne, ‘Did It Really Help to be a Japanese Colony? East Asian Economic Performance in Historical Perspective’, Japan Focus, Vol. 5, Issue 5 (2007)

[8] Yoon, Hong-Key, ‘Ch15 Iconographic Warfare and the Geomantic Landscape of Seoul’, in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books (1988): p. 281

[9] Han, Jung-san, “Japan in the Public Culture of South Korea, 1945-2000s: The Making and Remaking of Colonial Sites and Memories,” Japan Focus, Vol. 12, Issue 15, No. 2 (2014)

[10] Park, Yuna, ‘Controversy over architectural heritage from Japanese colonial era continues,’ The Korea Herald (Aug 10, 2020) http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200819000642 [Accessed 23/10/21]

[11] Han, Jung-san, “Japan in the Public Culture of South Korea, 1945-2000s: The Making and Remaking of Colonial Sites and Memories,” Japan Focus, Vol. 12, Issue 15, No. 2 (2014)

[12] Ibid

[13] Personal photograph from ‘Did the Colonial Japanese drive Spikes into Sacred Korean Mountains…?’ http://www.san-shin.org/Spikes-controversy.html [Accessed 23/10/21]

[14] Han, Jung-san, “Japan in the Public Culture of South Korea, 1945-2000s: The Making and Remaking of Colonial Sites and Memories,” Japan Focus, Vol. 12, Issue 15, No. 2 (2014)

[15] Ibid

[16] Yoon, Hong-Key, ‘Ch15 Iconographic Warfare and the Geomantic Landscape of Seoul’, in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books (1988): p. 304

Bibliography

- Booth, Anne, ‘Did It Really Help to be a Japanese Colony? East Asian Economic Performance in Historical Perspective’, Japan Focus, Vol. 5, Issue 5 (2007)

- Han, Jung-san, “Japan in the Public Culture of South Korea, 1945-2000s: The Making and Remaking of Colonial Sites and Memories,” Japan Focus, Vol. 12, Issue 15, No. 2 (2014)

- Park, Yuna, ‘Controversy over architectural heritage from Japanese colonial era continues,’ The Korea Herald (Aug 10, 2020) http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200819000642 [Accessed 23/10/21]

- Yoon, Hong-Key, ‘Ch14 The Social Construction of Kaesong,’ in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books (1988)

- Yoon, Hong-Key, ‘Ch15 Iconographic Warfare and the Geomantic Landscape of Seoul’, in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books (1988)

- ‘Did the Colonial Japanese drive Spikes into Sacred Korean Mountains…?’ http://www.san-shin.org/Spikes-controversy.html [Accessed 23/10/21]