How do we separate the unified to create division? For Georg Simmel, this began with the mental, whereby the perception of unity or division served to provide operational definitions for human activity, writing that ‘whether… connectedness or… separation is felt to be what was naturally ordained and the respective alternative is felt to be our task, is something that can guide all our activity.’[1] This understanding of human action being the result of either a push for division or fight for inclusion can help to enlighten our approach to underline some of the spatial driving forces of history.

For instance, one of the first governmental institutions established by the British in the colony of Rangoon was a lunatic asylum, which the British intended to be a place to exclude the colonially classified neurodivergent from society. To reify such a conception of separation, one of the first requests from the asylum’s superintendents in their annual reports to the Burmese government was for the construction of a wall around the currently unenclosed compound for the asylum’s civil inmates.[2] The wall’s desired effect of separating between the compound’s “inside” and “outside” was represented in the superintendent’s report a few years later[3]:

However, despite the existence of the wall as a delineation between “inside” and “outside” within the minds of the asylum’s planners, there was already a recognition that this illusion was being troubled in reality.

The attempt to nominate the asylum as an exclusionary space had failed since the authorities’ response to the superintendent’s initial request for a wall was the cheaper alternative of planting a bamboo hedge around the asylum’s perimeter.[4] By 1882, the superintendent raised the issue again as the bamboo was failing ‘to protect the patients from the gaze and impertinent curiosity of visitors and from… their presence.’[5] This posed an issue for the superintendent as he could not rigidly impose the labour routines, the moral education, and strict diets that the asylum’s staff believed were necessary to manage or cure the patients’ mental illnesses, since relatives from the town offered alternative sources for, or distractions from, all of these.[6] As family members continued to visit their relatives within the asylum despite the presence of the bamboo, the more significant issue of increasing numbers of escapes from the asylum led to renewed requests to improve the compound’s security, the existing lack thereof being reflected by a change in mapped representations of the asylum featuring a dashed rather than solid line around the civil compound[7]:

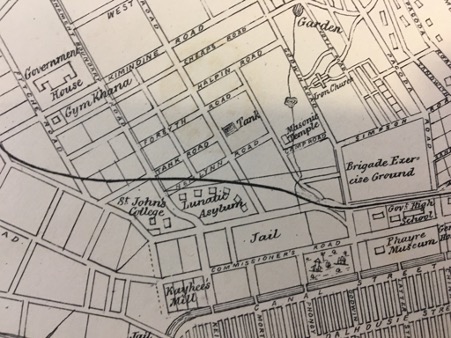

What is perhaps more notable is the representation of the asylum by J. C. Clancey from his visit to the town which depicts the asylum as a loose collection of buildings, as opposed to the clearly segregated space of the Rangoon Central Jail sitting opposite[8]:

What this map suggests is that the physical presence of a wall greatly influenced the perception of the purpose for its liminality as existing in the minds of the people walking by the institution; the jail is separated by a wall and the concept of a person’s criminality is understood to warrant their exclusion, while a person’s perceived neurodivergence does not necessitate their exclusion, especially if this is supposedly facilitated by a bamboo hedge.

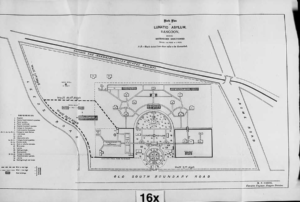

This is not to say that the construction of a wall would have altered how the people of Rangoon viewed neurodivergence overnight, but when the British did commit greater effort into making this an exclusionary institution, the effects on the differences between the town and the asylum’s inmates increased. This intensification was seen in 1929 when the inmates were moved to the town’s new mental hospital, as the asylum was renamed, at Tadagale where barbed wire fencing surrounded the entire compound.[9] Before this movement, while the medical approaches to treating various mental illness had changed to variable degrees and the issue of overcrowding had resulted in a growing proportion of the hospital’s population being criminal, there were still few reported incidents of escapees or released patients causing harm to the wider population. However, the new institution, with its more defined liminality and distance from the town’s general population, allowed for a greater securitisation of the inmates’ bodies and facilitated their increased subjection to new medical regimes. In comparison to the previous relative lack of violence enacted on the population of the town considered to be neuroconforming by the hospital’s inmates, when Fielding Hall issued an order to release the hospital’s population after a false alarm of a Japanese invasion, the town experienced repeated acts of violence and destruction as the British authorities lost all control over the activities of the released inmates.[10] What the causes of this destruction were deserves greater analysis, but the increased violence of the inmates on those not considered neurodivergent after the transition from the old asylum to the new hospital’s more exclusionary space is worth investigating.

This blog posting is not meant to present a complete history. However, it shows that Simmel’s suggestion of liminality as a driver for action and a framework for mentalities could provide us with new ways of viewing the effects of such liminality on historical events. As the history of Rangoon’s lunatic asylum suggests, rather than just dismissing the violence enacted after Fielding Hall’s actions as being the result of “madness”, it would be better to explain how this “madness” was constructed, what it meant, and how it became violent, with one possible explanation to all of these questions being the creation of exclusion through the erection of a wall by the British.

[1] Georg Simmel, Simmel on Culture: Selected Writings, (eds.) David Frisby & Mike Featherstone (London, 1997), 171.

[2] Report on the Rangoon Lunatic Asylum for the Year 1878 (Rangoon, 1879), 1.

[3] The Report on the Rangoon Lunatic Asylum for the Year 1882 (Rangoon, 1883).

[4] Report on the Rangoon Lunatic Asylum for the Year 1880 (Rangoon, 1881), 2.

[5] The Report on the Rangoon Lunatic Asylum for the Year 1882, 2.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Report on the Rangoon Lunatic Asylum for the Year 1893 (Rangoon, 1894).

[8] J. C. Clancey, Aid to Land-Surveying (Calcutta, 1882).

[9] Note on the Mental Hospitals in Burma for the Year 1929 (Rangoon, 1930), 1.

[10] Noel F. Singer, Old Rangoon: City of the Shwedagon (Stirling, 1995), 207.