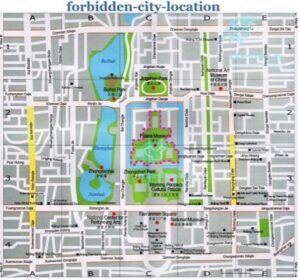

Jingshan Park in Beijing is located next to the Forbidden city. (Figure 1) For many years, this park has been imperial and not opened to the public until 1928. Like many other imperial places, the park was invaded and destroyed when foreign troops entered Beijing in the late imperial period. This blog will refer to a tour guide article published in 2012 on a local Chinese tourism website, to discuss the impact of historical traumas on the park’s architecture, asserting that despite the foreign invasion caused severe architectural destruction, a deliberate decision by the government for not restoring some Buddha statues within the traditional pavilions in Jingshan Park can further cultivate national sentiment. By selectively choosing which historical aspects to restore, the government intends to shape collective memory and crafting a shared narrative that resonates with the broader populace.

Figure 1. Map of Jingshan Park and the Forbidden city

Figure 1. Map of Jingshan Park and the Forbidden city

According to the website’s article, Jingshan Park has five traditional pavilions, each housing a copper Buddha statue representing one of the five tastes: sour, bitter, sweet, acrid, and salt.1 Regrettably, during the siege of the international legations in 1900, foreign soldiers removed four of these statues,2 directly compromising the integrity of the five tastes. There was only one statue in Wanchun Pavilion (Figure 2.) being preserved.

Figure 2. Wanchun Pavillion

Figure 2. Wanchun Pavillion

Although this statue was preserved during the 1900 event, it was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s when fervent individuals destroyed all Buddhist-related objects within the park.3 The removal of the first four statues symbolises the traumatic loss of Chinese traditional treasures due to Western powers, while the destruction of the second one mirrors the upheaval within Chinese society during the Cultural Revolution. Notably, the government’s response to these losses diverges. The Buddha statue, destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, was restored in 1998, signifying a commitment to reclaiming historical heritage. However, a proposal by Li Yuling in 2006 to restore the remaining four statues was rejected during the conference.4 This discrepancy in handling restoration projects reflects the government’s selective emphasis on historical narratives. Likely, the website does not mention the destruction of the statue in Wanchun Pavilion during the Cultural Revolution, underscoring the nuanced ways historical narratives are presented.

The historical narratives surrounding Jingshan Park reveal a discernible selectivity on the website, omitting certain facts and focusing on specific aspects. The absence of the four statues connected to the foreign invasion serves as a poignant reminder of a national tragedy inflicted by the West. Their non-restoration perpetuates a historical memory of loss, casting a shadow that lingers with visitors. The enduring pain of losing these traditional artifacts persists, leaving an impact on those who visit the remaining four pavilions. In contrast, the statue in Wanchun Pavilion, tied to internal chaos, underwent restoration in 1998. This act of restoration seeks to efface the traces of its destruction and erase the memory of violent actions carried out by the Chinese themselves. These selective restoration projects reflect the government’s effort to reshape historical narratives selectively. It brings to mind Zheng Wang’s book, Never Forget National Humiliation, where he introduces a concept of the Choseness-Myths-Trauma complex. He suggests that the government strategically select certain historical events to construct a chosen historical memory, invoking national sentiment.5 The revived statue in Wanchun Pavilion, distinct from the four forever-lost statues from the foreign occupation, symbolises the enduring Chinese tradition and spirit despite the challenges posed by Western invasion. It stands as a carefully chosen memorial object, contributing to the construction of a resilient national identity.

In this week’s elective reading on Taiwan park, the author highlights the replacement of Kodama Gentaro and Goto Shinpei’s statues with those of Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, claiming it demonstrates another type of ‘colonial’ occupation and changing political landscapes.6 This blog asserts that beyond the visual impact of statues, the absence of traditional objects in specific spaces can significantly contribute to shaping national sentiment and moulding selective historical memory. It posits that not only do specific historical events construct national sentiment, but the simultaneous presence and absence of exhibit items in historical spaces can also influence historical interpretations, directing the emphasis on sentiment and memory.

Figure 3. The restored Buddha statue in Wanchun Pavilion

Figure 3. The restored Buddha statue in Wanchun Pavilion

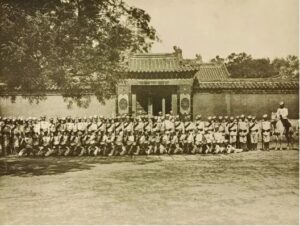

Figure 4. Russian Occupation of Jingshan Park, 1900

Figure 4. Russian Occupation of Jingshan Park, 1900

Bibliography

Primary Sources

‘Jingshan Park’, Travel China Guide, March 2012, < https://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/beijing/jingshan.htm> [accessed 29 January 2024].

Secondary Sources

Allen, Joseph R, ‘Taipei Park: Signs of Occupation’, The Journal of Asian Studies 66: 1 (2007), pp. 159–199, <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021911807000010> [accessed 29 January 2024].

“Jingshan Gongyuan de Wuzuo Tingzi” 景山公园的五座亭子, Beijingshi Renming Zhengfu 北京市人民政府(2017), https://www.beijing.gov.cn/renwen/jrbj/sjc/201703/t20170309_1874497.html.

“Luoshi Huifu Jingshan Wuting Lishiyuanmao Zhengxietian Jiaoliuhui Zaijingjuxing” 落实恢复景山五亭历史原貌政协提案交流会在京举行, Fojiao Zaxian (2006), https://web.archive.org/web/20140106033017/http://news.fjnet.com/jjdt/jjdtnr/200605/t20060524_26414.htm.

Wang, Zheng, Never forget national humiliation: Historical memory in Chinese politics and foreign relations (New York, 2014).

- ‘Jingshan Park’, Travel China Guide, March 2012, <https://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/beijing/jingshan.htm> [accessed 29 January 2024]. [↩]

- ‘Jingshan Park’. [↩]

- “Jingshan Gongyuan de Wuzuotingzi” 景山公园的五座亭子, Beijingshi Reming Zhengfu 北京市人民政府(2017), https://www.beijing.gov.cn/renwen/jrbj/sjc/201703/t20170309_1874497.html. [↩]

- “Luoshi Huifu Jingshan Wuting Lishiyuanmao Zhengxietian Jiaoliuhui Zaijingjuxing” 落实恢复景山五亭历史原貌政协提案交流会在京举行, Fojiao Zaxian (2006), https://web.archive.org/web/20140106033017/http://news.fjnet.com/jjdt/jjdtnr/200605/t20060524_26414.htm. [↩]

- Zheng Wang, Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations (New York, 2014), p. 39. [↩]

- Joseph R. Allen, ‘Taipei Park: Signs of Occupation’, The Journal of Asian Studies 66: 1 (2007), p. 177, <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021911807000010> [accessed 29 January 2024]. [↩]