Chua’s chapter “Modernism and the Vernacular” explains how the different spatial configurations of the kampung and of Chinese squatters’ housing led to different socialisations of “public space” in the modernist Housing Development Board (HDB) housing estate. The HDB’s vision was one of “overwhelming conformity” with some form of abstract designs of which their purpose is to “serve as ‘place markers’ in what would otherwise be placeless continuum of similarity.”1 While Chua’s chapter elucidates a theme central to the historiography of housing in post-colonial Singapore, Chua’s unilateral presentation of HDB’s housing vision can be nuanced by investigating the Singapore Institute of Architects (SIA) journal Rumah2 during the first phases of HDB’s development. The “modern” and the “vernacular” were envisioned as a possibility and spelt a vision of “public space” completely different to that of the HDB.

The SIA in its September 1961 issue presented the HDB’s raison d’être as one of continuity and change. The HDB’s initial work was launched off the final of the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT)’s reports on housing.3 Yet, this Report entailed the post-colonial government’s “basic reassessment of aims and policies” in terms of “rental of housing units, densities of development, standard of accommodation, scale of building programme and many others.” Geographically, the HDB would begin by renewing “obsolete properties in the central areas” before a gradual, radial process of undoing marginal, slum properties.4 This was in concert with the HDB chief architect Teh Cheang Wan, who agreed with the remit of the HDB in relation to SIT. His words were confirmed by Lim, who argued that this strategy was needed as a “lasting solution to the urban housing problem prior to major economic development, industrialisation and a basic solution to employment,” indeed emphasising that this would also be the terms the HDB would be judged on.5

Thus the SIA, while accommodating the aforementioned writings from both HDB officials, was also very deliberate with student development. The Student Section, while bearing the stamp of the Singapore Polytechnic Architectural Society (SPAS), was open to any letters from the public. The SPAS also seemed aligned with how Chua characterises the HDB – “modern architects’ socialist sentiments” infused with the early twentieth century British “Garden City” movement.6 The page bore the SPAS’ “manifesto” – in which students emphasised the primacy of “public spaces”, “parking facilities” and the relationships buildings held within the unit of a formalised “Town Plan.”7

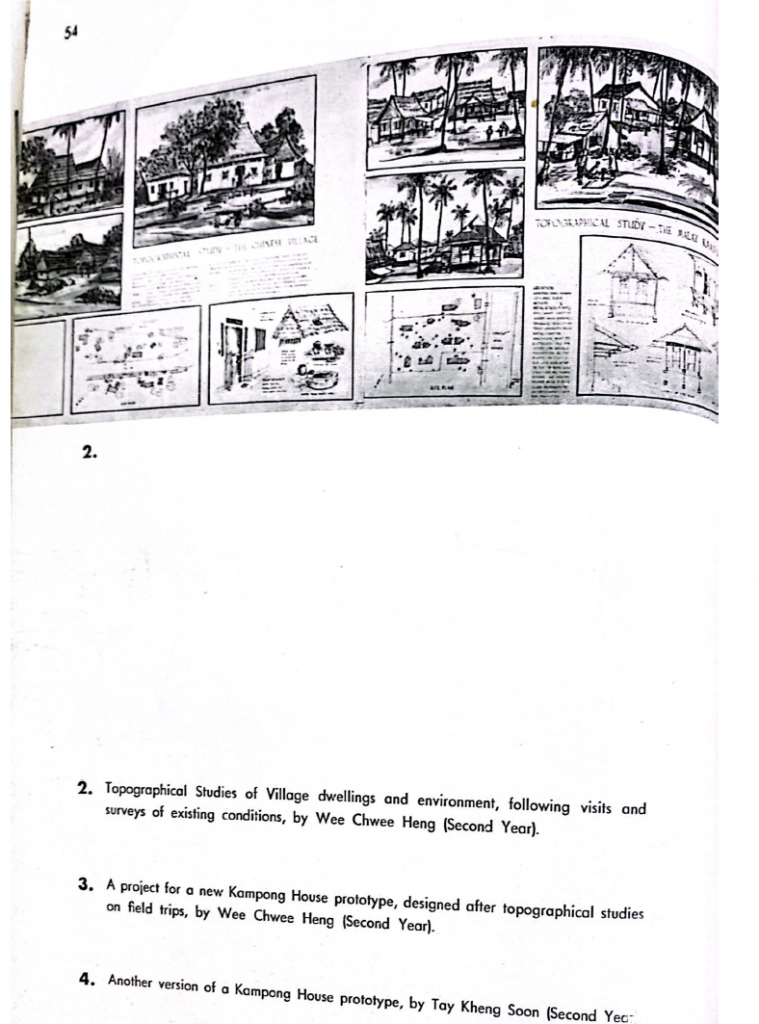

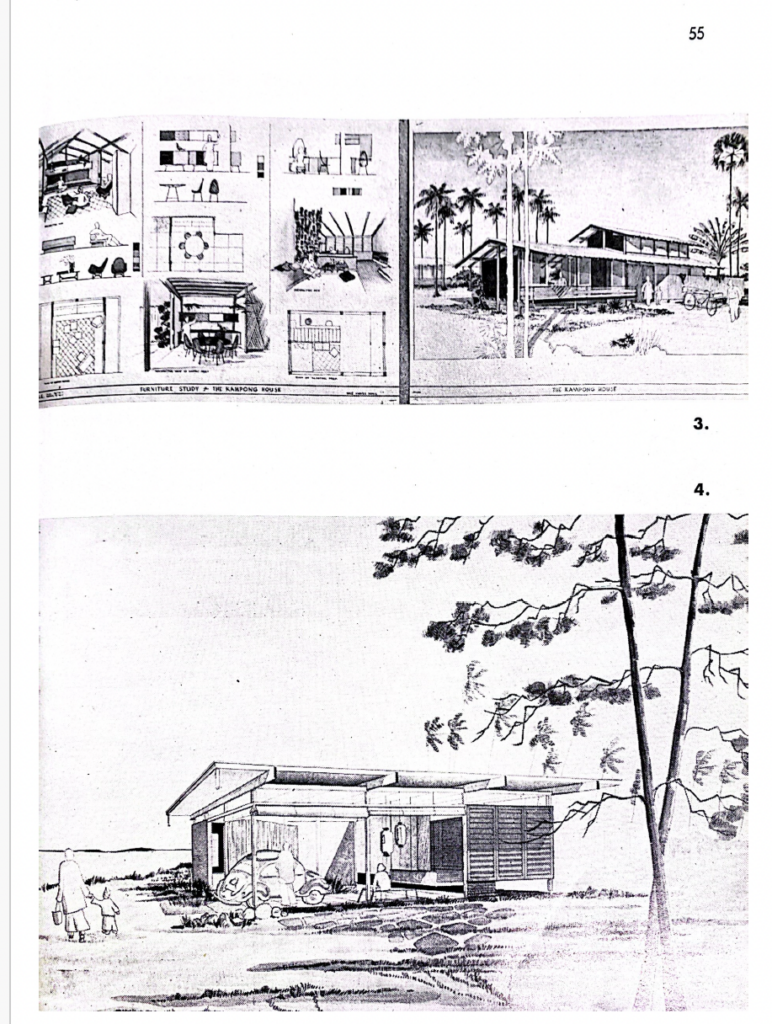

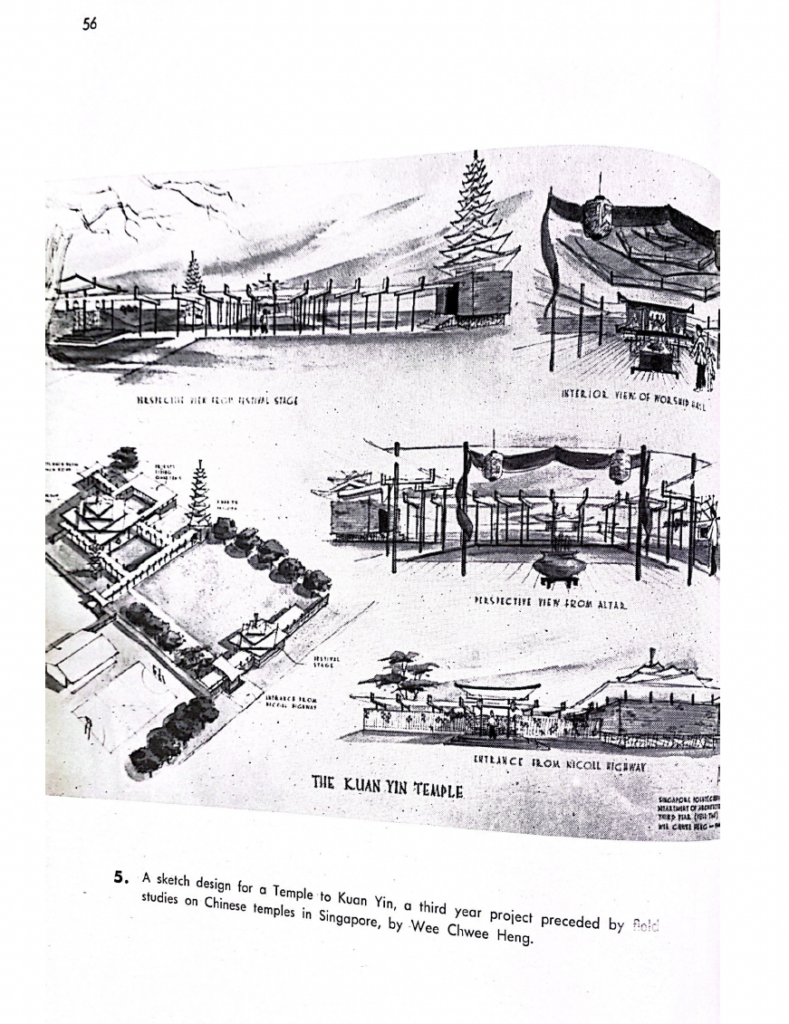

Pages 54-56 of the “Student Section” of Rumah, Sep 1961

However, the entries in this issue were just as concerned with the “vernacular”. All the entries were concerned with “Village dwellings”, with Second Year student Wee Chwee Heng’s entry detailing a topographical study following fieldwork Wee conducted. Wee was also the only student to submit a design for a “Temple to Kuan Yin” which he submitted as a “third year project preceded by field studies on Chinese temples in Singapore.” In contrast with schematics that Chua uses in his chapter, Wee focused his drawings on wide-angled views rather than bird’s eye projections of his studies. Wee’s drawings place the “vernacular” firmly within the “modern” – his temple is designed with an “entrance from Nicoll Highway.”8

The bulk of the other drawings responsed to a call for a “Kampong House prototype”, including an entry by Tay Kheng Soon when he was still a Second Year student. Tay’s envisioning of a kampung on stilts visualises the elements that Chua describes in the kampung – the clear features of the stilts and the serambi (verandah) are immediately obvious. Yet, just like Wee, Tay’s conception of the “vernacular” kampung house imagined both “modern” and “vernacular”. Tay pictures a car pulling into the paved flooring, leaving still a bench in the serambi for a resident to use, even if the car’s intrusion into this “public space” is not clear. In fact, Wee’s last submission bears a similar imagination in “prototyping” a “Kampong House” focused on envisioning the “modern” and the “vernacular”. Yet, both students did not identify “public” space necessarily as an area of discontinuity, and instead found ways of picturing them both inside and outside the kampung.4 For these architectural students, therefore, Rumah columns became a platform for experimentation – just as public housing would eventually become for the HDB.

- Beng Huat Chua, Political Legitimacy and Housing: Singapore’s Stakeholder Society (London: Routledge, 2002), 74-75. [↩]

- Bahasa Melayu for “Home” [↩]

- The Report is not available in the issue but is discussed by William Lim. Lim later gained prominence for his architectural achievements and social activism. William SW Lim, “The Singapore Improvement Trust 1959,” in Rumah (Sep 1961): 58-59. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩]

- All quotes are from Teh’s article is at the front of the issue. Teh, “Public Housing in Singapore,” in Rumah (Sep 1961): 5-9. [↩]

- Chua, Political Legitimacy and Housing, 75. [↩]

- “Student Section,” in Rumah (Sep 1961): 49. [↩]

- “Student Section,” in Rumah (Sep 1961): 54-56. [↩]