Hong Kong’s housing today is known for its unaffordability and sky-high rents due to limited space. Hong Kong has a population greater than Scotland but its total available land area is less than half of Greater London which explains why housing remains a constant problem in one of the world’s most densely populated metropolises.1 In spite of this, Hong Kong actually has a rather unique history of housing, especially the public housing realm that has permeated throughout society as a result of British policy measures to combat poverty and discontent as the bulk of the Hong Kong population initially saw them as Chinese and Hong Kong to them was a temporary place to do business before returning to their homeland, thus breeding the phrase coined by Richard Hughes, “Borrowed place, borrowed time.”. (Richard Hughes, Hong Kong: Borrowed Place, Borrowed Time, 1966)

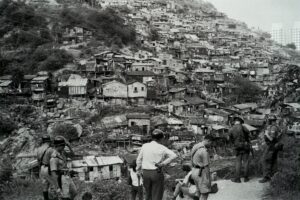

In order to cope with the increasing population, demand for housing and the realisation that Mao Zedong’s Communist Party’s hold on China will be permanent, the British colonial government decided that housing the population and housing reform would need to be undertaken. Contrary to popular belief that the 1967 riots marked the start of public housing provision in Hong Kong, it was actually the 1953 Shek Kip Mei fire that made the government start building flats to accommodate people as it was poor conditions of squattered areas consisting of wooden houses and corrugated iron sheets.2. Interestingly enough, my maternal grandmother and grandfather, both of whom were poor immigrants from neighbouring Guangdong province arrived in Hong Kong during the 1950s and initially settled in a poor, squattered housing, but was then resettled in a public housing complex under the Hong Kong government’s colonial scheme. In order to pay my tribute to them, I will focus this article on analysing how Hong Kong’s public housing estates contributed to a new sense of identity and gave individuals hope to abandon the sojourner mentality as described by Hughes above. For this, I will focus on a newspaper report from Wah Kiu Yat Po from December 1963, when Choi Hung Estate, where my mother and her brothers and sisters grew up was completed.

Figure 1: A typical squattered area or slum in Hong Kong during the 1950s – 60s, Source: South China Morning Post

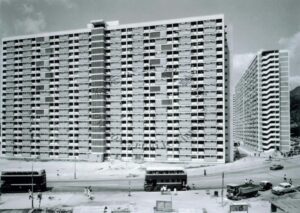

Figure 2: View of Choi Hung Estate from Kwun Tong Road (1963) Source: flickr

The news report, published on December 19th 1963 presented the inauguration of Choi Hung Estate by then British governor Robert Black as an important ceremony for the city as the newspaper quoted in the headlines stating it is the ‘largest project of the city’ and the contents mentioning officials from the housing department, civilian affairs attending it.3 The public housing scheme was seen as a watershed moment for the city for both the British and local Chinese residents. That is because for the British, the Hong Kong housing plan is the most vigorous and dynamic project ever undertaken that was not seen in other places in the world besides Singapore and that housing a large population with limited resources is certainly no easy feat. As for the local residents, it built a sense of community spirit amongst residents that started to envision that Hong Kong is their home and that they will be there to stay, thus planting the seeds of a unique ‘Hong Konger’ identity, which was seen in the next decade under the governorship of Murray Maclehose.4 Although I did not personally grow up in a public housing estate myself, but I had to say that this undoubtedly changed Hong Kong permanently and affected who I am today as my parents, who were sons and daughters of poor individuals from China who benefitted from the resettlement scheme was able to enjoy better living conditions and more access to secondary and tertiary education opportunities, hence showcasing how housing plays a key role in raising population approval in terms of governance and that increasing opportunities can change societal fabrics. As a result, it is evident that housing policy can directly alter the course of history on a certain place’s development.

Furthermore, this example ties to the wider theme in the compulsory reading. That is because as seen in the Tianjin reading, during the time when multiple foreign powers had their own zones, each attempted to use their own styles of housing to instill in the minds of the Chinese people on what it means to be ‘modern’.5 Additionally, the Meiji government in Japan attempted to construct Western methods of sanitations and dwellings in order to turn the Japanese into a ‘civilised’ race.6 Therefore, it is evident that there is a continuum that demonstrates the effective and central role housing plays in governance and constructing modernity.

- Tim Summers, China’s Hong Kong, Politics of a Global City, 2019, pp. 127-135 [↩]

- Steve Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong, 2003, p. 204 [↩]

- Wah Kiu Yat Po, December 19th 1963: https://mmis.hkpl.gov.hk/coverpage/-/coverpage/view?_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_hsf=%E5%BD%A9%E8%99%B9%E9%82%A8&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_actual_q=%28%20verbatim_dc.collection%3A%28%22Old%5C%20HK%5C%20Newspapers%22%29%20%29%20AND+%28%20%28%20allTermsMandatory%3A%28true%29%20OR+all_dc.title%3A%28%E5%BD%A9%E8%99%B9%E9%82%A8%29%20OR+all_dc.creator%3A%28%E5%BD%A9%E8%99%B9%E9%82%A8%29%20OR+all_dc.contributor%3A%28%E5%BD%A9%E8%99%B9%E9%82%A8%29%20OR+all_dc.subject%3A%28%E5%BD%A9%E8%99%B9%E9%82%A8%29%20OR+fulltext%3A%28%E5%BD%A9%E8%99%B9%E9%82%A8%29%20OR+all_dc.description%3A%28%E5%BD%A9%E8%99%B9%E9%82%A8%29%20%29%20%29&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_sort_field=score&p_r_p_-1078056564_c=QF757YsWv5%2FH7zGe%2FKF%2BFApeJWgOkWwE&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_o=2&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_sort_order=desc&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_filter=dc.publicationdate_dt%3A%5B1960-01-01T00%3A00%3A00Z+TO+1969-12-31T15%3A59%3A59Z%5D) By putting resources into public housing, it implies that the British colonial government is trying to introduce measures that aims to solve the most pressing problem in Hong Kong at the time, which is affordable housing and having a roof. As mentioned in the article, each apartment does not have its own bathroom or kitchen and each apartment has an average space of 300 sq ft. It can be seen as a massive milestone for the colony, as prior to the beginning of the scheme, the government constantly faced budget constraints and lack of policy direction in order to implement this plan, but within the timespan of a decade, the government managed to co-ordinate and build over seven public housing estate, each being able to house over a total of 100,000 residents of a population of nearly 3.4 million. (( Steve Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong, 2003, pp. 204-205 [↩]

- Steve Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong, 2003, pp. 204-205 [↩]

- Elizabeth LaCouture, Dwelling in the House, Family, House and Home in Tianjin, China, 1860 – 1960, 2021 [↩]

- Jordan Sand, House and Home in Modern Japan: Reforming Everyday Life 1880 – 1930, 2005 [↩]