Jordan Sand in House and Home argues that Meiji Era social reformers redefined the meaning of “home” and the roles of the persons physically present in the “home” for the sake of the nation-state. In selectively maintaining continuity with agreeable tenets of hitherto home life while simultaneously co-opting Taylorist practices pertaining to “home” in the West, Sand argued that Meiji Era journals, school curricula and newspapers reproduced this new praxis of the “home”. In line with Sand’s approach to studying the reproduction of “home”, I have examined the Lee Fatt Furniture & Electrical Company’s 1968 product brochure and its advertising in Singapore newspapers between 1964 and 1973 just as the nascent Housing Development Board (HDB) began to widen its public housing. Its brochure and advertising strategy, I argue, refracted both a shift in a rent-based to a leasehold-ownership-based form of housing ownership and characterised the new homeowner as the individual seeking upward socio-economic mobility on behalf of one’s family.

At the time of the People Action Party (PAP)’s attainment of internal self-government from the British, the PAP had inherited a growing population that had either been “living in over-congested shophouses in the city area” or in “wood-panel and thatched-roof houses in urban-fringe kampong”.1 Within a decade, the HDB had resettled much of the population into public housing flats; and by the turn of the twenty-first century 90% of Singaporeans lived in public housing. Most owners of these state-subsidised flats hold their flats under leasehold “homeownership” for a period of 99 years. The HDB’s work in public housing was and remains “the PAP government’s signal achievement, as a testament to its social democratic impulse, and as a foundation of its legitimacy and longevity in parliamentary power.”2

In recency, socio-economic studies3 of public housing have served as an avenue of texturing the unevenness of the physical safety and low-cost, multi-cultural harmony that housing ministries and statutory boards argue Singaporean public housing has helped to engender. Historically, however, this apparently linear trajectory only took place after 1964. Between 1960 and 1964, its first batches of flats required tenants to share toilets, bathrooms and laundry spaces; representing not much of an improvement over the hitherto predominant housing conditions available for the masses. In 1964, however, two important schemes changed the nature of public housing and home ownership. The HDB upgraded its provisions by starting production of “three-room flats, which referred to two bedrooms and one sitting room in HDB nomenclature” not including a kitchen and a bathroom-cum-toilet.4 Furthermore, the introduction of the Home Ownership Scheme alleviated financial difficulties for prospective homeowners and eased the financing of HDB flats that had hitherto been meant as rental flats. Further changes after 1964 allowed individuals to use their social security savings to offset the costs of purchasing flats. This newfound model of ownership, and widened accessibility, can be gleaned through a host of newspaper advertisements and brochures distributed by furnishing and electrical companies in the 1960s and 1970s.

Lee Fatt Furniture & Electrical (利發木器傢俬) belonged in this category as a furniture and electrical supplier that took root in the 1960s. It placed its first furniture advertisement ion 26 November 1964.5 In 1966, it opened a new branch at 14 Jalan Tiong, in addition to its existing headquarters at the former Nelson Road, and in 1968 it published a 40-page brochure that was targeted at the growing number of new home owners in Singapore. The brochure a variety of household furniture items such as desk chairs and mattresses, advertisements from associated retailers and a range of household appliances. On page 1 its preface emphasised its “various modern designed” goods that were “exquisitely and exclusively designed” for the new prospective homeowner, while offering furniture that could be “made to order according to specific designs, and if necessary, with the guidance of our experts.”6

Beyond the front of the brochure, Lee Fatt wrote on the last page of the brochure its personalised messages to prospective patrons in Bahasa Melayu, Mandarin and English. One reason for this may have been the abundance of available Mandarin-language books in Singapore in this period which had its first pages at what we would consider the “end” of the book. Its messaging, subconsciously or otherwise, envisioned its customer base as new homeowners who were on the cusp of a new phase beyond just “modernity” but the uplift of a “happy family”. The messaging in Bahasa was gender neutral, appealing to both men and women (“tuan2/puan2”) while the messaging in Mandarin phrased purchases as “for the sake of one’s family” (“曾否打算為你的家庭佈置一套精緻!舒適!耐用的傢俬”).7

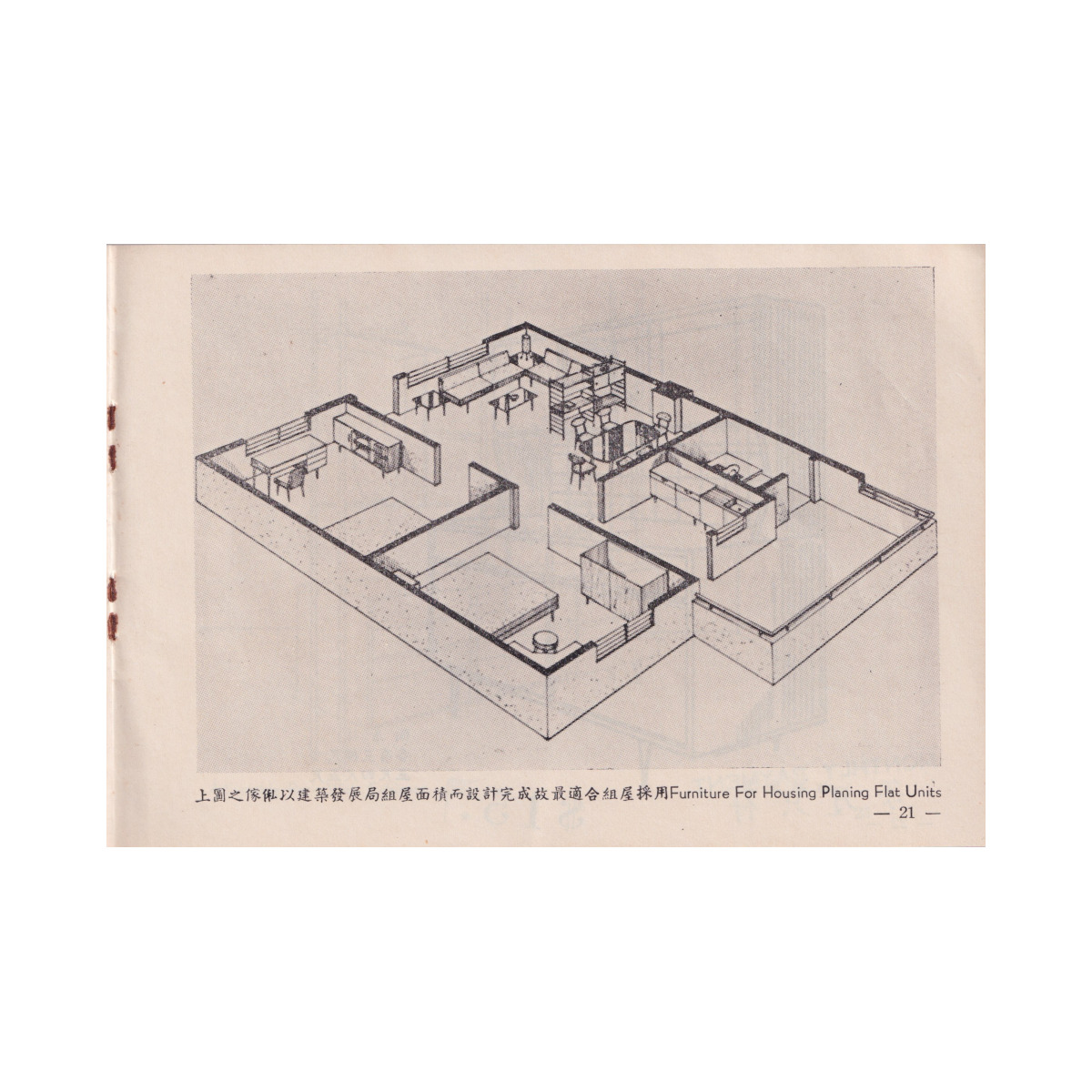

Lee Fatt’s brochure even alluded directly to the new model of a HDB flat. Page 21 of its brochure idealised how furniture would fill space in a blueprint of a three-room flat. The image showed a three-room flat with cabinets, beds, lamps, desks and sofas in a configuration that was idealised as befitting a new family. The caption made explicit mention, writing in English that this image was an ideal of “Furniture For Housing Planning [sic.] Flat Units”. In Mandarin, the link was more explicit, writing that this envisioning pertained specifically to the regulations and parameters of a new HDB flat (“以建築發展局組屋面積而設計完成故最適合組屋採用”).(( Ibid., 21 ))

Therefore, when situated in relation to the HDB’s burgeoning capabilities, the Lee Fatt brochure is an exciting source that suggests the particularities of advertising and consumer culture in the 1960s. This cursory exploration of the brochure encourages further research possibilities across different media, languages and economies of consumption in post-colonial Singapore.

- Beng Huat Chua, Liberalism Disavowed (New York: Cornell, 2017), 73-76. [↩]

- Ibid., 75. [↩]

- For an example see: Annas Bin Mahmud, ‘“There You Eat, There You Sleep, There You Study”: Housing Concerns and Needs of Low-Income Malay HDB Tenants in Singapore’. M.A. Thesis, National University of Singapore (Singapore), 2020. [↩]

- Chua, Liberalism Disavowed, 75-76. [↩]

- Advertisements Column 5, The Straits Times, 26 November 1964, 19. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19641126-1.2.116.5 NewspaperSG (accessed November 14, 2023) [↩]

- “Lee Fatt Furniture & Electrical (利發木器傢俬),” Singapore Graphic Archives, 1. [↩]

- Ibid., 40 [↩]