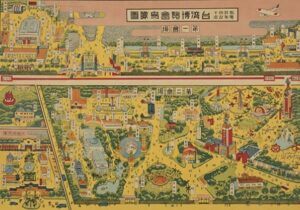

Fig 1. ‘The 1935 Taiwan Exposition: In Commemoration of the First 40 Years of Colonial Rule’, Source: ‘Special Exhibition: Back in their times: a visual history of Taiwan from the 1930s to the 1960s’, The 228 Memorial Foundation, accessed 9th of October 2023, Special Exhibition|Back in their times: a visual history of Taiwan from the 1930s to the 1960s|Memorial Foundation of 228.National 228 Memorial Museum

This map by famed aerial artist Hatsusaburō Yoshida of ‘The 1935 Taiwan Exposition: In Commemoration of the First 40 Years of Colonial Rule’ is representative of Japan’s desire to project their ideas of utopian modernism to the rest of the world and to mainland Japan. Their rational of modernising to protect themselves from, and surpass western empires is somewhat undercut by the fact that their concept of the modern were inherently modelled, at least spatially speaking, from said international influences.

The map itself is keeping with a trend of colonial mapmaking that emerged in the 1930s which combines Japanese pictorialism with new photographic technology, specifically aerial photos. This genre of maps have been classified as Chōkanzu and were notable for their bird’s eye view perspective, 3 dimensional representation, colourful design and most importantly, picturesque quality (1). Looking at maps with this style it becomes quickly apparent that the intended audience for the map was not the urban planner, engineer or government official but the tourist. As Allen asserts, it gives the localities it depicts a ‘postcard destination’ quality (2).

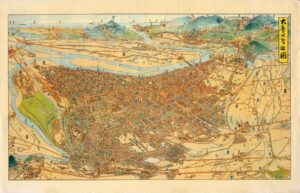

Below is another example of Taipei represented in this style on the eve of the 1935 Taiwan Exposition.

Fig 2. ‘Bird’s Eye Map of Greater Taipei’, Source: Keoni Everington, ”Colorful ‘Bird’s Eye View of Taipei” Japanese map circa 1935, Taiwan News, (13th of January, 2017), Colorful ‘Bird’s Eye View of Taipei” Japanese map circa 1935 | Taiwan News | 2017-01-13 18:30:00

Between them there are distinctive similarities: the detailed architecture, the scroll labelling and iconography of both transport and industry, and of leisurely parks and nature. They both simultaneously portray an image of a cosmopolitan and prosperous nation, and a luxurious and leisurely travel destination. They exist as publicly accessible texts that visualise the city in modern and idealistic terms. While they exist as Japanese colonial propaganda, they do so in different ways. The ‘Bird’s Eye Map of Greater Taipei’ on its own encapsulates Japanese colonial ideology by its foregrounding of Japanese settlements over Chinese areas, and the fictious geographic placing over the water of Japan’s iconic Mount Fuji and other colonies – Korea and Manchukuo. As Allen asserts, this representation is one of possession and desire (3).

While this map can be seen as product of colonial ideology, the 1935 Exposition Map is reliant on the context of the Exposition and the general phenomenon of world exhibitions. As such this map can be seen as a sub product of the propaganda that was the 1935 Taiwan Exposition. Following the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, world exhibitions took on its model of showcasing industry, architecture, and technology, mixing private, public and governmental institutions for a tourist and consumer audience. Japan was one of the nations, and the first non-western empire, to be inspired by this model. It held several exhibitions in Osaka and Tokyo between 1877 and 1911. It soon also held exhibitions in its colonial territories, including one in Taipei in 1916, however the later exposition in 1935 was considered the greatest of all the colonial exhibitions. This was at least partially a consequence of the significance of the event, the celebration of the 40th anniversary of Japanese rule in Taiwan. The island was important symbolically to Japan as its first colony; if any part of its empire was going to demonstrate the power of Japanese imperialism to the rest of the world, it was Taiwan. As Gotō Shinpei declared, Taiwan was the ‘colonization university’ and the first ‘to demonstrate that Japan was the equal of Western Imperialists’ (4). As Young asserts, this desire to modernise and compete with western nations drove much of the architecture building in later colonial projects like the Manchurian cities (5).

In order to celebrate its power, the exposition was structured over 3 main sites, two in Taipei and one in Da-Dao-Cheng. The first site centred around Taihoku City Public Auditorium (now Zhongshan Hall) and was populated with: pavilions showcasing Taiwanese industries, the Hall of Encouraging New Trade and the Hall of Prefectural Affairs which highlighted other Japanese colonies like Manchuria and Korea. The second took place in Taihoku New Park (now 228 Peace Memorial Park) focused on more social and cultural transformations in Taiwan, with an open air theatre, a cinema house, the musical hall and the First Cultural Hall, previously the Taiwan museum, which discussed the process of educated modernisation. The third site largely focused on tourism and recreational activities in Taiwan (6). Through this arrangement visitors were able to experience several dichotomies: present and future, production and consumption, governmental and private, citizen and tourist, Western and Asian, colony and colonial state.

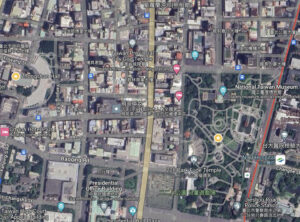

Returning to the representation of this event in the Chōkanzu map, it depicts the two main sites of the Exposition. For the sake of unity and practicality, it distorts these two sites to be spatially connected. While close in distance, the google maps show that it skips over two blocks worth of space.

Fig 3. Satellite Map of the two Exposition sites. Left side Taihoku City Public Auditorium (Zhongshan Hall) and site one, right star aihoku New Park (now 228 Peace Memorial Park). Source: Google Maps

This erasure of urban space is also visibly seen is the map as well, as blocks of buildings are represented as grey, formless masses. While this could have been designed to highlight relevant buildings to exposition, it does partly function to make this urban image cleaner and more spacious. This is certainly the case with the roads, which are enlarged significantly in the map. In general, wider streets and more parks were two primary goals in housing and urban reform that planners were seeking in Japan (7). This is why the decision to place an Exposition site in a park, and the exaggerated representation of nature in the map , is significant as the green spaces in colonial cities were often far greater than what the average mainland Japanese urban dweller saw. Therefore, while the Expositions were trying to make an international statement, they were also trying to indicate to Japanese that the colonies were places that could achieve the reform and progress that was thus far unachievable on the mainland.

Finally, what’s important to note about this map is the architectural design visible in the Exposition buildings. While there is a mix of styles present across the map, the influence of European design is clear, specifically in two key sites of the Exposition: The Taihoku City Public Auditorium and the Taiwan Museum. Moreover, Ping-Sheng Wu and Min-Fu Hsu assert that many of the pavilions were in the art deco style (see below), a style that some Japanese architects in Manchuria thought they should use to reflect modern trends (8).

Fig 4. (Left) The Hall of Sugar Industry. Fig 5. (right) The Main Gate of the First. Source: Ping-Sheng Wu, and Min-Fu Hsu. “Phantasmagoric Venues from the West to the East: Studies on the Great Exhibition (1851) and the Taiwan Exhibition (1935).” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 5;2, (2006), pp.237-244, p.242

While their goal was to make a statement to the international community about Asian design, ultimately Bill Sewell argued that the Japanese were generally more concerned about joining European aesthetics, than overhauling them (9). Thus, any attempt by the Japanese to prove their superiority over the West was naturally undercut by the fact they were often working within Western concepts of modernist. What’s more ironic about the development of the New Asian style in the 1930s was that much of the international ‘modern’ designs they were modelling from, were seen as increasingly irrelevant by the rest of the world.

While most of the blog post has discussed what this map tells us about Japanese Imperialism and their concept of the modern, it hasn’t yet discussed what this representation meant to the Taiwanese. This map was found amongst an online photo exhibit entitled: ‘Back in their times: a visual history of Taiwan from the 1930s to the 1960s’ on a website called the Memorial Foundation of 228 (10). The page states its last update was from 2021. What’s striking is that, despite the 20 year difference the description that Allen gives of the 1999 exhibition ‘Old Maps of Taipei and the 2004 exhibition ‘Viewing Taipei’, matches this website too – namely that they overwhelmingly positively focus on Japanese colonial historical contributions and downplay and ridicule Chinese nationalist attempts. While attempts to appear modern to an international audience may have been slightly undercut, to the Taiwanese people at least they have cemented a place as authors of modernity and development.

Overall, as a historical document this map represents the ideals and contradictions of Japanese modernist propaganda, particularly in its presentation to mainland Japan and the rest of the world. However, as an item in a Taiwanese historical collection, it raises questions about how Taiwanese view the Japanese colonial period, and what

(1) Joseph R. Allen, Taipei: City of Displacements, (University of Washington Press, 2012), p.37

(2) Allen, ‘Taipei: City of Displacements, p.37

(3) Ibid, p.38

(4) Ping-Sheng Wu, and Min-Fu Hsu. “Phantasmagoric Venues from the West to the East: Studies on the Great Exhibition (1851) and the Taiwan Exhibition (1935).” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 5;2, (2006), pp.237-244, p.241

(5) Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, Twentieth-Century Japan (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 1999), pp.241-268.

(6) Wu, Hsu, “Phantasmagoric Venues’, p. 242

(7) Tucker, David “City Planning Without Cities: Order and Chaos in Utopian Manchukuo” in Mariko Asano Tamanoi ed., Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire, (University of Hawaii Press, 2005.), pp.53-81, p.57

(8) Wu, Hsu, “Phantasmagoric Venues’, p. 242, and Sewell, Bill. Constructing Empire: The Japanese in Changchun, 1905–45. (UBC Press, 2019.), p. 69-71

(9) Sewell, ‘Constructing Empire’, p.71

(10) ‘Special Exhibition: Back in their times: a visual history of Taiwan from the 1930s to the 1960s’, The 228 Memorial Foundation, accessed 9th of October 2023