The life of a gangster is never simple or pleasant. Not least the life of the ‘Godfather’ of Shanghai, a city crawling with endless opportunities for ambitious criminals. Du Yuesheng’s life of lawlessness was borne out of a troubled childhood, with the early loss of his parents and his sister being sold into slavery. From an early age, Du grew an appetite for gambling and gaming, an aspect of his personality that Martin claims, ‘instilled in him a certain self-discipline that curbed his natural outbursts of violent temper.’1 This is likely a trait that aided his rise to leadership of the Green Gang, one of the world’s most infamous secret criminal organisations. This blog aims to consider the life of the gangster against the unique backdrop of extraterritoriality and Japanese occupation. Whilst his full story is worthy of a full and extensive biography (see Zhang Jungu and Xu Zhucheng’s accounts), this post will highlight his rise to prominence and maintenance thereof in the labyrinthine political environment and dark and murky spaces of Old Shanghai.

After a childhood of petty hooliganism, theft and mischief, he impressed the then ‘bigshot’ of the Green Gang, Huang Jinrong, whose power derived from his illustrious and efficient career as the leader of the Chinese detective squad in Shanghai’s French Concession. His ability to negotiate and extort from his network of informants and contacts was paramount to his power. Wakeman’s depiction of these detective squads highlights their inescapable association with the criminal underworld.3 Whilst supposedly ‘solving crimes’, they were also assisting their allies in trafficking opium, running brothels, casinos and protection rackets.4 Having impressed Huang, Du swore the oath of brotherhood to the Gang and quickly began to make his impression. Martin notes how his full embracing of secret society values and rituals and ‘rags to riches’ story helped generate influence of ‘legendary proportions’.5Indeed, power over the Green Gang was his after Huang Jinrong’s arrest in 1924. It is extremely important to note this ‘reputation’, which, comparably to Chicago’s Al Capone won him political clout and influence in elite government circles. His dominance of the opium trade, which remained rife throughout the Nanjing Decade, drew him close to General Chiang Kai Shek, leader of the Republic. Images like the one below, have in many ways come to crystallise the social space of Shanghai as decadent, debauched and rife with vice. The narco-economy was seen as a vital source of income for the Republic, and it is characteristic that Du was put in charge of the ‘Shanghai Opium Suppression Bureau’, which ultimately gave the Green Gang a monopoly of the market and extra income from tax and license fees.6 Such a bureau indeed simply acted as a guise for the government to control and earn more revenue.

The spaces Du Yuesheng controlled and operated were spaces of shade and criminality and in a city like Shanghai this made him important to the invading Japanese force in 1937. By 1939, the Japanese had offered Du safe passage and protection to Shanghai (having fled after backing the Kuomintang Army), to mobilise the Green Gang and operate the opium trade on their behalf.8Perhaps in a move out of character, he turned down the opportunity, instead favouring to find his own ways of smuggling opium into Japanese territory. Why he did this is unclear, however it is likely he was still ideologically committed to Chiang and Dai Li and preferred to supply his narcotics to the Nationalists. This puzzling decision is perhaps representative of the complex network of relationships between gangs, their rivals, businesses, municipal councils and invading forces in Shanghai. Indeed, Du himself could not conquer all of Shanghai. The Shanghai Municipal Police were a constant foe in his battle to deal opium legally in the International Settlement.9

A key aspect of Du’s administration of power was his extensive network of secrets and his control over hierarchy. An example of this was his ‘Endurance Club’, which was a smaller collective of individuals with social standing considered useful to Du. Elites such as industrialists, financiers, police and government officials were all brought into a clandestine arrangement which Du administered personally.10The operation of such a club relied on the practice of secrecy. Sworn oaths, rackets and protection payments kept the Endurance Club running. One can imagine the teahouses and mansions such meetings Du would have held and the spatial practices that would have characterised them. A meeting with Big-Eared Du would have been intimidating and daunting. Those to displease him or speake out of turn would have been few and far between.

The remainder of Du’s story, outlined in detail by his biographers, is one of relative anti-climax. After the conclusion of Japanese occupation, he was not welcomed back to Shanghai, bringing an end to his premiership as the City’s mob boss. He appears to have travelled to Taiwan and Hong Kong, but much of this period remains unclear.

A fascinating spatial history of his houses and meeting places is waiting to be written. One suspects it may lack the glitz, glamour and romanticism of his American counterparts; however, his operation was remarkable and had a profound effect on Shanghai’s reputation as the Asian capital of vice.

- Brian G. Martin, “The Shanghai Green Gang: Politics and Organized Crime, 1919–1937” (Berkeley, 1996) p. 41 [↩]

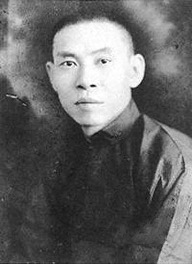

- Du Yuesheng, c. 1930, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Du_Yuesheng#/media/File:Du_Yuesheng2.jpg [↩]

- Frederic Wakeman Jr., “Policing Modern Shanghai”, The China Quarterly, No. 115 (Sep. 1988), p. 415 [↩]

- Zou Huilin, “Du, the godfather of Shanghai”, Shanghai Star, (June, 2001), Accessed 7 March 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20070821130553/http://app1.chinadaily.com.cn/star/2001/0607/cu18-2.html [↩]

- Martin, “The Shanghai Green Gang”, p. 40 [↩]

- Zheng Yangwen, “Shanghai Vice”, in The Social Life of Opium in China, (Cambridge, 2012), p.191, Frederic Wakeman Jr., The Shanghai Badlands: Wartime Terrorism and Urban Crime 1937-41, (Berkeley, 1996), p.11 [↩]

- Opium Den,1932, https://audiovis.nac.gov.pl/obraz/236216/ecf2fad8b7dbbd753701f03be2bbef34/, [↩]

- Wakeman Jr., The Shanghai Badlands, p.12 [↩]

- Martin, “The Shanghai Green Gang”, p. 180 [↩]

- Ibid, p. 181 [↩]