In 1905, the Mitsui Dry Goods Store changed its name to Mitsukoshi and began advertising itself as Japan’s first department store. The original store was founded in 1673, but it went through a long process of transformation to become the modern department store that exists today. In 1878, it began hosting bazaars where the public would take off their shoes before wandering through the stalls of goods, and in 1904, the addition of windows to the storefront allowed people to look in at goods from the street.1 While many of the innovations Mitsukoshi implemented were modeled on Western department stores, Mitsukoshi created its own unique “department store experience” and its branch stores in colonial Korea and Dalian enjoyed similar success when they opened in the 1930s.2

Despite Mitsukoshi’s popularity in Japan and Southeast Asia, it was less successful in the United States. In 1979, it opened its first branch in New York in an effort to “learn more about the American market and equalize the Japanese United States balance of trade.”3 It opened its doors just as another Japanese department store, the Takashimaya company was reducing the size of its Fifth Avenue location. The Takashimaya Company also began “shifting to primarily American products from largely Japanese because of the rising price of the Japanese merchandise.”4 Despite its goal of learning about American markets, the New York branch of Mitsukoshi closed in the 1990s. While the failure of Mitsukoshi in New York was attributed to economic factors, it is essential to note that the products and experiences that department stores offer their customers are tailored to the place itself and its consumption culture. In New York for instance, consumers were less interested in expensive Japanese products from a brand without widespread recognition in the United States.

The difficulties of adapting shopping experiences to new markets went in both directions. Although certain aspects of Japanese department stores were modeled on Western department stores, this does not mean those stores were universally successful when transplanted to Japan. Like the Mitsukoshi in New York, Ikea failed to adapt to the needs of Japanese consumers. In 1974, Ikea entered the Japanese market but by 1986 all locations had closed. This was attributed partly to different consumer habits, as “Japanese consumers at that time were not ready for the ‘self-service and self assembly’ concept because Japanese consumers were only accustomed to a high level of service,” but also to the spatial practices of the Japanese. Japanese homes and living spaces tend to be smaller and “the Scandinavian style furniture from Sweden did not fit small-space living.”5

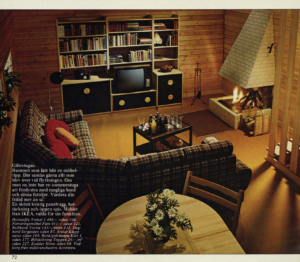

“1974 Ikea Catalogue,” Ikea Museum, 72 https://ikeamuseum.com/en/digital/ikea-catalogues-through-the-ages/1970s-ikea-catalogues/1974-ikea-catalogue/.

In 2006, Ikea relaunched in Japan with new strategies for adapting to the Japanese market. A recent series of promotional videos on how to furnish tiny homes with Ikea products demonstrates the store’s recognition that their products must to cater to the specific spatial needs of Japanese customers.6

Like Mitsukoshi, Ikea failed to adapt to consumer habits and spatial needs. While department store models often appear transferable, the success of a department store depends on more than management and appearances. In a comparison of shopping malls, Lizzy van Leeuwen notes that “although the design and management strategies of shopping malls are rather standardized all over the globe, the social configurations of these centres of consumption differ remarkably at local levels.”7 The social and spatial configurations of department stores are just as unique at local levels and stores must take into account the experience of shopping as well as the specific needs and spatial practices of their customers.

- Brian Moeran, “The Birth of the Japanese Department Store,” in Asian Department Stores, ed. Kerrie L. MacPherson (London: Routledge, 1998). [↩]

- Aso, Noriko, “Mitsukoshi’s Expansion Before 1945” Bodies and Structures 2.0: Deep-Mapping Modern East Asian History. [↩]

- “Mitsukoshi Opens Here.” The New York Times, March 16, 1979. https://www.nytimes.com/1979/03/16/archives/mitsukoshi-opens-here.html. [↩]

- “Mitsukoshi Opens Here.” [↩]

- Thy Nguyen, Yingdan Cai, & Adrian Evans, “Organisational learning and consumer learning in foreign markets: A case study of IKEA in Japan,” Paper presented at The British Academy of Management 2018 Conference, UWE Bristol, UK (2018), 9. [↩]

- WK Tokyo, “IKEA |Tiny Homes Episode 2: Small Space Visions,” YouTube, December 21, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=60KL3p-M27k. [↩]

- Lizzy van Leeuwen, “Celebrating Civil Society in the Shopping Malls,” in Lost in Mall: An Ethnography of Middle-Class Jakarta in the 1990s (2011), 162. [↩]