‘China’s cities seem especially—in many respects increasingly—inhospitable to community self-determination and participation in environmental design’1

Urban Planning has proven to be difficult when accommodating a large population and according to Daniel Abramson within his article Messy Urbanism and Space for Community Engagement in China, there is a common theme of these urban areas becoming messy because of the lack of community engagement within urban development. However, to understand how messy urbanism is approached and improved, sanitation efforts enable a better insight as to how developers have been able to boost community spirt, while also cleaning up living spaces and streets. By the 1950’s China seems determined to clean up its urban spaces, and connect the public through the concept of being involved in improving sanitation together.

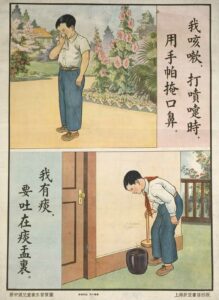

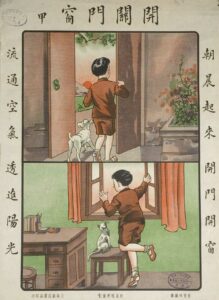

There are sanitation posters targeted at both children and adults to help them learn how to improve their hygiene and avoid the spread of diseases. These posters also provide insight towards Daniel Abramson’s argument which states that China would not follow the West in spreading out its population to smaller scale areas to avoid messy urbanism, instead he states that modernity was the point of interest rather than urbanity, and they were determined to push the cities into a modern state of living. Therefore, these posters from 1930 to 1950 show the progression of educating urban populations to enable the possibility of ridding the cities of messy urbanisation, while also allowing China to push towards its modern goal. To do this they needed social control of the population to enable these plans for larger streets and skyscraper buildings to become reality. Sanitation would change the state of minds and allow the community identity to accept the modernisation of their city. Below are two examples of how sanitisation was promoted towards children to catch germs and improve the living conditions of their homes.

Translation: I cover my mouth when I cough, and I spit into spittoon2

Translation: Let air circulate – open windows and doors in the morning3

‘Architectural chaos therefore also reflects a continuity and strength of community composition and identity. The coexistence of built-environmental disorder with community social order is extremely contradictory to the minds of professional planners and officials in China.’4

Furthermore, these plans to modernise China and allow space for wide streets and less enclosed living spaces could only go so far without demolishing Chinas traditional architecture. Instead, the traditional and modern began to coexist, which almost contradicted the idea of reducing messy urbanism. However, what can be argued is that through sanitation development and education, China improved its community values and enabled living spaces to change without changing. Those who lived within messy urban areas began to understand how to look after themselves and others to avoid spreading diseases, which would have been and still is a large concern within overpopulated areas. By regulating hygiene behaviours and introducing new sanitation protocols, messy areas could still modernise, while also being able to accommodate such a large population.

- Daniel Benjamin Abramson, Messy Urbanism: Understanding the “Other” Cities of Asia (Hong Kong University Press, 2016) p.218. [↩]

- Hygiene Education for Children (U.S National Library of Medicine, 1950) [↩]

- Hygiene Education for Children (U.S National Library of Medicine, 1935). [↩]

- Daniel Benjamin Abramson, Messy Urbanism: Understanding the “Other” Cities of Asia (Hong Kong University Press, 2016) p.225 [↩]