Taipei, on the northern peninsula of Taiwan, has been referred to as a ‘tripartite city’ by Joseph R. Allen, Professor Emeritus at the University of Minnesota.1 Under Japanese occupation, it arguably underwent a third layer of urban developmental influence. The island of Taiwan had been used to foreign influence, for as early as the 17th century, the island had been occupied by the Dutch Empire (known as Dutch Formosa). The island really rose to significance in the late 19th century under the control of the late Qing Dynasty. In 1877, Chinese restrictions on immigration to the island were lifted and Taipei in particular became a focal point for trade, development and activity.

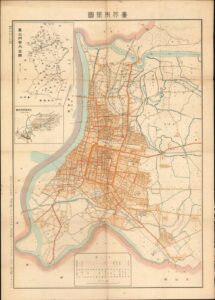

Although Liu Mingchuan, Qing Governor of Taipei until 1891 had implemented several key reforms to Taipei, it was not really until the Japanese colonists arrived that modernity really felt like it was on the horizon. Kodama Gentaro, the Japanese Governor General and Goto Shinpei, a civil administrator were the main architects of Taihoku’s development. Shinpei, who would later go on to serve as director of the South Manchuria Railway and Mayor of Tokyo, had been educated in Germany.2 Allen has alluded to the fact that Shinpei was also heavily influenced by Tokyo. In turn, Tokyo’s development had drawn many ideas from European cities such as Paris. Maps, such as the below from 1932, with ruler straight streets and a clear gridiron structure, really show how Taipei had been influenced by European colonial projects.

Taipei, even into the present day, as pointed out by Allen, has often considered itself a multicultural city. Away from Chinese mainland, and outwith the central power structure of the Chinese Communist Party, the city has always had a complex identity. Tan Hung-Jen and Paul Waley’s article ‘Planning Through Procrastination: The Preservation of Taipei’s Cultural Heritage’ discusses Dihua Street in Taipei, containing a number of late imperial edifices and buildings from the Japanese colonial period.4 The municipal government, property owners, stakeholders and citizens have all made an effort in varying ways to preserve these buildings as an important part of Taipei’s cultural identity. Additionally, buildings such as the Sotokofu, the main government building of Taipei and the Guest House (Táiběi Bīnguǎn), located in the city’s central district, were built by the Japanese and show a clear architectural and stylistic link to Europe. These buildings of grandeur, magnificence and opulence are typical of the domineering and grand style of buildings built under colonial and imperial rules. These buildings remain prominent today. The lack of ‘Chinese-ness’, as Allen describes it, can be much attributed to the Japanese era.

When one looks to understand the development of any space, place or spatial entity, one must understand and critically analyse the sources from which they are working. Allen cites the historian John Tagg, who maintains that even the ‘meaning’ from photographic evidence is dependent on the ‘discursive system’ and context within which it was taken.5When working with cartographic materials of Taipei as well, the same level of analysis must be used. For example, Allen’s article outlines the ‘lush’ maps of Taihoku the Japanese produced in the 1930s. Designed not with cartographic accuracy in mind, for they were meant to be understood and widely consumed ‘by women and children’, they show a bustling city, with buses, trains, commerce and activity. Taihoku is depicted as a well-run, prosperous and disciplined city, with all thanks to the Japanese imperial project. One image in particular, showing the city from a ‘bird’s eye’ perspective, looks out towards the sea and displays Mount Fuji standing tall and proud in the distance.6 To what extent are these depictions merely trying to emphasise the reward of colonial possession and desire?

The development of ‘utopian spaces’, especially in the context of colonial expansion, must always be considered carefully. For island cities like Taipei, their cultural identity, and the urban developments that often accompany them are politically contested phenomena. Is the island of Taiwan off the coast of China? Or is it off the coast of Japan? Many of the images that have come to light recently, raised by Allen in his article, have resurfaced only after exhibitions instigated by the Taipei City Cultural Affairs Bureau.7 With relations continuing to be strained between the ROC and the PRC, the nostalgia and romanticism of the many images from the Japanese period must be noted. Although clearly the Japanese prioritised the development of Taihoku, and indeed charted and archived much of their significant progress, one must always seek to understand why images have been constructed and re-presented in certain ways.

- Joseph R. Allen, Taipei: City of Displacements (Washington, 2012), p. 31 [↩]

- Louis Frédéric, Japan Encyclopaedia, (Harvard, 2002), p. 6 [↩]

- 1932 Murasaki City Plan or Map of Taipei, Taiwan [↩]

- Tan Hung-Jen and Paul Waley. “Planning through Procrastination: The Preservation of Taipei’s Cultural Heritage” The Town Planning Review 77, no. 5 (2006), pp. 531–55 [↩]

- Allen, Taipei: City of Displacements, p. 33 [↩]

- Ibid, p. 39 [↩]

- Ibid, p. 17 [↩]