Within Henri Lefebvre’s work, The Critique of the Everyday, alienation is introduced as a tool of political and economic exclusion of the lower classes.[1] He critiques how the design of Paris came to exclude the non-elites by driving them further away from the city centre, creating an increasingly disruptive and distant space between their domesticity and their place of work.[2]

The exclusivity of the town centre and the alienation of the other represents a politicisation of space that is exemplary in formal colonial town planning processes. Peter Hall demonstrates how the most formalised application of alienation was Luyten’s Delhi, as the city was reimagined and reorganised under a complicated hierarchy of race, social rank and affluency.[3] Those who ranked in the upper echelons of British colonial society remained in the centre while the less affluent and local residences were pushed outwards. The new city centre was a symbol of British political power, and the city was to be remodelled as an Eastern Rome.[4] This new Eastern Rome arguably applied only to areas of European domesticity, recreation and work as the Indian outskirts did not fall under formal town planning processes other than their physical distance to the central metropole.

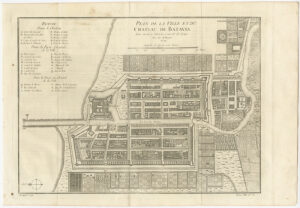

Much like Delhi, Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) also represents spatial exclusion but in a less formalised manner. The 1750 map of Batavia created by Jacques Nicolas Bellin demonstrates the alienation of the other in his representation of Batavia’s inner and outer city.[5] The map was created after the 1740 Batavia Massacre that saw the expulsion of the Chinese Batavian population outside the city walls.[6] Although they were allowed back into the walls, a sizable Chinese settlement was already formed called Glodok, directly south of the city walls.[7] The placement and representation of Glodok exemplifies Lefebvre’s notion of spatial alienation as it is applied as a tool of political and economic exclusion of the lower classes.

The placement of Glodok outside the city walls is the primary symbol of exclusion as the wall creates a physical barrier between the European and the Chinese populations.[8] From Bellin’s map, it appears that Glodok also became alienated from the formal Dutch town planning processes. The map demonstrates a stark difference between the constructions of the two districts. The inner walled city is planned in a grid-like structure with wide streets and large housing. Space is abundant, and infrastructure for transportation such as bridges between canals are frequent between blocks. Glodok appears dense with smaller plots of housing organised in a non-grid like structure. Districts are constructed to fit the geographical shape of the land in between the southern walls and the Ciliwung River. Streets appear to be narrower, and bridges between rivers are less frequent. The physical representation of Glodok highlights an alienation of the Chinese population outside both the city walls and outside the formal town planning processes of the Dutch.

Spatial alienation also appears representationally as Bellin’s map highlights a dominant trend amongst most cartographic representations of Batavia during this time period.[9] Maps are arguably political, they can be an inclusionary tool as they represent physical space for a wider audience. However, they can also be exclusionary as cartographers can oversimplify or exclude space from their representation. Bellin’s 1760 construction of Batavia follows a clear trend of exclusion as it provides a detailed representation of each district, street and river within the city walls as it represents the European community’s domestic, recreational and professional space.[10] However, Glodok and areas outside of the city walls remain anonymous. Glodok fails even to be labelled while the settlements east and west of the city walls are identically produced illustrations of plantations.[11] Outside the periphery of the European community, Glodok appears as a dead space, negligible in terms of individual agency or political and economic activity.

Although Bellin’s map is not representative of Chinese or Javanese lived space, it is valuable in presenting the effects of spatial alienation in colonial cities. Alienation appears in two forms; it exists as a physical and representational act of exclusion as it demonstrates a space that lives outside the European periphery.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Bellin, Jacques, Plan de la Ville et du Chateau de Batavia (1750). Image in Bartelle Gallery (BG-11199), <https://bartelegallery.com/product/map-of-batavia-bellin-1750/> [accessed 9th October 2021].

Krevelt, A.V. Peta Batavia 1780. Image in Batavia Digital <https://bataviadigital.perpusnas.go.id/peta/?box=detail&id_record=10&npage=1&search_key=&search_val=&status_key=&dpage=1> [accessed 9th October 2021]

Pemerintah Kolonial Belanda, Peta Batavia 1672. Image in Batavia Digital <https://bataviadigital.perpusnas.go.id/peta/?box=detail&id_record=15&npage=1&search_key=&search_val=&status_key=&dpage=1> [accessed 9th October 2021].

Surjomihardjo, Abdurrachman. Peta Batavia 1650. Image in Batavia Digital, <https://bataviadigital.perpusnas.go.id/peta/?box=detail&id_record=14&npage=1&search_key=&search_val=&status_key=&dpage=1> [accessed 9th October 2021]

Secondary Sources:

Hall, Peter. Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design since 1880 (New York, 2014).

Jingga, Fanny and Yulia Nurliani Lukito, “Ethnic Identity and its response to the growing environment in the urban space of Glodok, Jakarta.” AIP Conference Proceedings Online Volume 2376, issue 1 (2021), pp. 1-6.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Critique of Everyday Life Volume I (New York, 1948).

[1] Henri Lefebvre, The Critique of Everyday Life Volume I (New York, 1948), p. 148.

[2] Ibid., pp. 229-230.

[3] Peter Hall, Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design since 1880 (New York, 2014), pp. 212-223.

[4] Ibid., p. 212.

[5] Jacques Bellin, Plan de la Ville et du Chateau de Batavia, (1750).

[6] Fanny Jingga and Yulia Nurliani Lukito, “Ethnic Identity and its response to the growing environment in the urban space of Glodok, Jakarta”, AIP Conference Proceedings Online Volume 2376, Issue 1 (2021), pp. 3-4.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Bellin, Chateau de Batavia.

[9] Bellin, Chateau de Batavia; Abdurrachman Surjomihardjo, Peta Batavia 1650, (Batavia Digital); A.v. Krevelt, Peta Batavia 1780 (Batavia Digital); Pemerintah Kolonial Belanda, Peta Batavia 1672, (Batavia Digital).

[10] Bellin, Chateau de Batavia.

[11] Ibid.