In her article ‘The Raj on Nanjing Road’, Isabella Jackson illustrates the crucial role played by Sikh policemen in the Shanghai International Settlement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[1] This reflects the wider importance of Indians to the Imperial project, fulfilling myriad roles across British territories in East and South East Asia. I was therefore interested to read James Warren’s article ‘The Rangoon Jail Riot of 1930’, which details the unique role played by Indians in the prison administration of British Burma.[2] Whilst significant similarities exist between these groups of Indians abroad, it becomes clear that their experiences could vary hugely, according to the prestige of their respective occupations, as well as the local context of their employment.

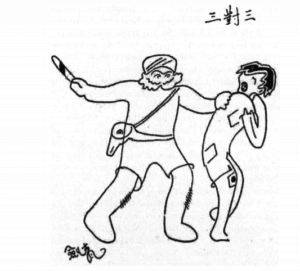

At first glance, Indians serving abroad seem to have been united by their subjection to racist, derogatory attitudes from indigenous peoples. Certainly, this seems true of Shanghai Sikh policemen, who even today are vilified in much Chinese history as ‘hongtou asan’ (Red-headed monkeys), perceived as vicious stooges of oppressive colonial rule.[3] Sikh policemen were for example blamed by the Chinese for opening fire on Chinese protesters in 1925, in the now infamous May 30th Incident.[4]

Fig. 1. Cartoon of a Sikh Policeman hitting a Chinese rickshaw puller. (Jackson, ‘The Raj on Nanjing Road’, p.1686

This is mirrored in the case of Burma, where, by the early 20th century, the entire population of prison wardens was Indian. In 1930, a huge riot broke out in the Rangoon Central Jail, with the ostensible aim of killing the superintendent, Major Bharucha. This reflected a long history of Burmese racially aggravated attacks against Indian prison staff.[5] Nor was racism confined to native Burmese, with the British enquiry into the riot laying the blame squarely at the feet of major Bharucha. He was described as both a bully and a coward, unsubstantiated accusations were made of his brutality, and he was summarily dismissed from his position.[6]

Whilst superficially similar however, it would be wrong to homogenise the experience of Indians in British service abroad. Working conditions appear to have been relatively good for Sikh policemen in Shanghai, attracting mainly ex-sepoys with the promise of pay five times greater than the Indian army, as well as the offer of nine months leave upon completion of five years service.[7] In the Burmese case by contrast, becoming a prison warden remained an unappealing prospect, with very low pay and long working hours. Indeed, according to a report by the Indian Jails Committee, an Indian jail warden was ‘but little less of a prisoner than the inmates whom it is his duty to guard’.[8] It would be wrong therefore to claim that Indians had a single, universal reason for seeking British employment abroad, with different opportunities instead being marketed at different subcategories within Indian society.

Moreover, the racism directed at Indians could spring from very different roots. In the Shanghai case for example, Sikh police became a ‘surrogate target for Chinese resentment of Euro-American Imperialism’.[9] Whilst this was also surely true in Burma, attitudes towards Indians in Rangoon likely had an economic dimension as well. The early 20th century had seen mass Indian immigration into Rangoon to work as unskilled labour. This led to growing competition with local Burmese, resulting in a huge race-riot in 1930 directed against Indian dock workers, resulting in over 500 deaths.[10] Seen in this context, anti-Indian sentiment could therefore spring from a number of locally derived sources, rather than exclusively from their association with the British.

Robert Bickers has concluded that Indians were employed by the British Empire for the three interlinked processes of ‘economy, defence, and display’.[11] Whilst this fundamentally seems to hold true, we should not let this obscure the very real differences in both how the British empire used its Indian subjects, as well as how such Indians were received by the local population. Whilst I have considered only two cases in this post, a more comprehensive study comparing the different experiences of Indian communities abroad would therefore be valuable.

[1] Isabella Jackson, ‘The Raj on Nanjing Road: Sikh Policemen in Treaty-Port Shanghai’, in Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 46, No. 6 (2012), pp.1672-1704

[2] James Warren, ‘The Rangoon Jail Riot of 1930 and the Prison Administration of British Burma’ in South East Asia Research, Vol. 10, No. 1 (2002), pp.5-29

[3] Jackson, ‘The Raj on Nanjing Road’, p.1675

[4] Ibid.

[5] Warren, ‘The Rangoon Jail Riot of 1930’, p.21

[6] Ibid., pp.13-14

[7] Jackson, ‘The Raj on Nanjing Road’, p.1680

[8] Warren, ‘The Rangoon Jail Riot of 1930’, p.22-23

[9] Jackson, ‘The Raj on Nanjing Road’, p.1691

[10] Warren, ‘The Rangoon Jail Riot of 1930’, p.11

[11] Jackson, ‘The Raj on Nanjing Road’, p.1676