The anthropologist Dean MacCannell argues that the tourist embodies the search for authenticity away from our daily lives.1 While modern mass tourism certainly grew more feasible as a result of greater mobility, safety, and disposable income, the demand for it increased due to the alienation inherent in the modern age.2 The Officiele Vereeniging voor Touristenverkeer, translated as the Official Tourist Bureau or OTB, was founded in 1908 to promote international tourism in the Dutch East Indies and did so by tapping into the modern need for perceived authenticity. By analysing visual tourist material produced by the OTB, as well as material produced by colonial transport companies such as KLM and KPM, we can analyse the different discourses which they utilised to capture the tourist’s desire for the authentic.

Figure 1: Trips in the Isle of Java, OTB 1909

Figure 2: Java: The Ideal Tourist Resort, OTB 1914

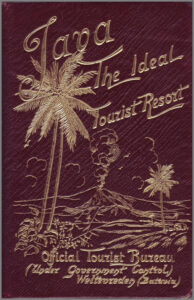

Figure 3: See Java, OTB 1937

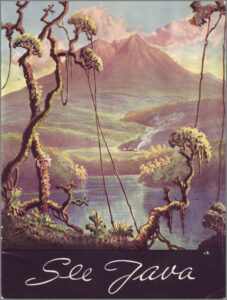

Most prominent in the tourist material produced by the OTB for Java is the theme of unspoilt nature. From the earliest publications to the material produced just before World War 2, brochures depicted the same scene of tropical flora set before an imposing volcano in the background. Even early proposed itineraries were preoccupied with the natural, mandating visits to the Botanical Gardens at Buitenzorg (Bogor), as well as recommending stays at the garden’s mountain branch at Cibodas, or a summit of Mount Gede.3 Nature was authenticity in its purest form. MacCannell describes it as the “original other”, once a uniting fear but in the modern world a source of awe and refreshed perspective.4 Even where evidence of human settlement is seen, as in Figure 3’s lonesome smoke plume, it is sparse and only serves to heighten this sense of awe through comparison between the grand scale of nature and the humble existence of humans. Of course, association between the tropics and vibrant nature was by this point an established trope, built upon the works of Humboldt and other early travel writers who formed the tropics in the western imagination.5 However, in Java, Robert Cribb argues that the theme of unspoilt nature is so prominent because early tourism followed the line of least resistance. It promoted areas where transport and accommodation were most readily available. On Java, these spaces were the colonial hill stations.6 As a result, the authenticity promoted for Java is the nature which would have surrounded the early Dutch colonisers on their retreats to the cool foothills.

Figure 4: OTB

Figure 5: KLM

Figure 6: KPM 1928

The dominating image for Bali, on the other hand, is the bare-chested woman. The roots of this stereotype derive from western image makers residing in Bali in the early 20th century. Men like Walter Spies and Dr Julius Jacobs, while also giving focus to the island’s culture, built upon pre-existing notions of tropical sensuality to produce an image of a sexually liberal Bali.7 This hybrid depiction of Balinese people, inclined towards sexual overindulgence but culturally richer than other “primitive” tropical races, made the people of Bali an alluring attraction.8 For Europeans and Americans who lived through the rigours of the First World War and the Great Depression respectively, this type of freedom offered an escape from their repressive societies.9 Bali had only been fully annexed by the Dutch in 1908 and so still retained much of its wild and mysterious image. The encouragement of this image by official arms of the Dutch colonial regime points to an attempt to profit off of another form of commercialised authenticity. Rather than awe-inspiring nature taking centre stage, it was interaction with Bali’s people, charming and untouched by modern convention as they were, which proffered the chance to experience the authenticity that was missing from modern western life.

Thus, we can see how the OTB and other arms of the Dutch colonial regime appealed to different aspects of “authenticity” in two parts of their empire: Java and Bali. While Java may have been the tamest, most heavily agriculturally exploited part of the Dutch East Indies, it nevertheless was branded as a paradisiacal, natural garden. This drew in tourists hoping to be refreshed by exposure to nature. In the case of Bali, its people were leveraged to present a promise of simplistic living and moral freedom. The Balinese could be thought to be living in a close to natural state, thus acting as an alluring proxy to access authenticity. Touristic materials can thus help us engage with the international discourses surrounding native landscapes and peoples, as well as telling us about the needs and desires of targeted western audiences.

- Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (London, 1976). [↩]

- Shelley Baranowski et al., ‘Tourism and Empire’, Journal of Tourism History 7:1 (2015), p. 113. [↩]

- Robert Cribb, ‘International Tourism in Java, 1900-1930’, South East Asia Research 3:2 (1995), p. 198. [↩]

- Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (London, 1976), p. 81. [↩]

- David Arnold, The Tropics and the Traveling Gaze: India, Landscape, and Science, 1800-1856 (Washington, 2006), p. 113. [↩]

- Robert Cribb, ‘International Tourism in Java, 1900-1930’, South East Asia Research 3:2 (1995), p. 202. [↩]

- Adrian Vickers, Bali: A Paradise Created (Berkeley, 1989). [↩]

- Ibid, p. 127. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 142. [↩]

Newspaper Article: Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight ((‘Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight’, Los Angeles Times, January 1915.))

Newspaper Article: Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight ((‘Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight’, Los Angeles Times, January 1915.)) Figure 1. The replica of Beijing’s ‘Forbidden City’.

Figure 1. The replica of Beijing’s ‘Forbidden City’.