Confessions of a Mask, originally published in 1949, was responsible for launching its author, Yukio Mishima to national fame. The novel follows its narrator, Ko-chan, as he struggles to fit into Imperial Japanese society. However, it is the final scene, set in a Tokyo dancehall during the American occupation, which is of particular spatial interest. As shown by Mackie and Field, novels were an important medium of representation of social spaces in Japan and China respectively.1 By analysing literary representations of the dancehall, we can learn about how they were imagined, not only by the author who described them, but by the wider society for which the novel was written. Though the dancehall presented in Confessions of a Mask is probably not a wholly accurate portrayal of any real establishment, it gives us insight into the connotations such spaces would have had for sections of the Japanese public, and their place within cultural discourse.

What is most apparent in Mishima’s description of the dancehall is its popularity. The intensity of the crowd within is emphasised as “cheek pressed against sweaty cheek” (pg. 198), and people extend their lunchbreaks to dance their fill. Indeed, during the post-war period, Japanese dancehalls were one of the rare sites of prosperity. Articles published in the Nippon Times testified to, and explained, the popularity of social dance spaces, arguing that they allowed ‘‘liberation from rigid wartime restrictions’’ and were representative of the growth of a new ‘‘democratic life”.2 This popularity meant profit. According to the Japan Times in 1948, the average dance hall musician received about 20,000 yen per month, compared to the basic wage of 3,000 yen for most office workers.3 Dancehalls were especially important sites of labour for veterans who had received musical training in the armed forces. Famous musicians such as the singer Oida Toshio, clarinettist Miyama Toshiyuki, and saxophonist Oda Satoru were among those who were able to successfully transition to civilian life.4 As such, Mishima’s bustling dancehall reflects the prominent place dancehalls held in the post-war Japanese zeitgeist, not only in its very use in the final scene of the novel, but in its textual description.

The novel also indicates the demographics and roles one expected to find within a dancehall. The first description of the hall’s interior notes that the crowd mainly consisted of office workers (pg. 198). The emergent figure of the “salaryman”, to which this is most probably referring to, represented the growing group of male white-collar workers who arose in Japan’s urban landscape in the early twentieth century. Their patronage of the dancehall indicates that such spaces were perceived as domains for male consumption. The few women in the scene, such as Ko-chan’s companion Sonoko to whom the dancehall is an unfamiliar space, are either brought there by men or are working hostesses. Mackie’s assertion of dancehalls as contradictory, gendered sites, supplying commodified leisure for men and labour for women, is thus corroborated.5

Lastly, the overt Americanisation of the dancehall reveals the cultural connotations these spaces would have held for Mishima and many others in Japan at the time. Mishima’s dancehall is almost overfilled with western music, Coca-Cola, and Hawai’ian shirts, all hallmarks of American culture. As Mackie argues, the dancehall was a venue where new structures of Euro-American hegemony could be enacted and reproduced.6 In fact, dance halls had been banned during the war but were reopened during the occupation to cater for Allied soldier.7 However, the image presented by Mishima clashes with the Mackie’s claim that while the dancehalls of the 1920s and 30s had been associated with modernity and Western dress, those of the Occupation catered to Allied expectations of exoticism.8 It is at this point we must consider the constructed, fictional nature of the novel as a source. Rather than naturalistically reflecting reality, Mishima’s writing was inevitably swayed by his fears over the loss of Japanese identity, and thus overemphasises the visibility of American culture.9 Such rhetoric is nevertheless useful, as while Occupation Japanese dancehalls may not have been so overtly Americanised as portrayed in Confessions of a Mask, they were certainly associated heavily with the Allied troops to which they owed their reestablishment. This inherent historical association between dancehalls and the Occupation makes it a convincing scene for Mishima to display his cultural concerns.

Mishima’s dancehall is thus a flawed, yet useful, reflection of reality. It seems to accurately capture the clientele and popularity of dancehalls in the post-war period and alludes to their gendered nature. However, his overly Americanised portrayal is more historically problematic. Rather, this segment of the novel can tell us about how social dancing spaces were positioned in the mind of the Japanese public. Post-war dancehalls were inextricably linked with western influence, and represented a new Japan, reborn from the desolation of war but irrevocably changed. Using a novel as a historical source thus lets us analyse how spaces were imagined by the public, providing a subjective perspective into how contemporary people constructed certain spaces in their own minds.

- Vera Mackie, ‘Sweat, Perfume, and Tabacco’ in Modern Girls on the Go, eds. Alissa Freedman, Laura Miller, and Christine Yano (2018) and Andrew Field, Shanghai’s Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Modernity in Old Shanghai, 1919-1954 (2010). [↩]

- E. Taylor Atkins, Blue Nippon: Authenticating Jazz in Japan (2001), pg. 187. [↩]

- Ibid, pg. 176 [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Vera Mackie, ‘Sweat, Perfume, and Tabacco’ in Modern Girls on the Go, eds. Alissa Freedman, Laura Miller, and Christine Yano (2018), pg. 74. [↩]

- Ibid, pg. 82. [↩]

- Ibid, pg. 79. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Damian Flanagan, Yukio Mishima (2014), pg. 8. [↩]

Newspaper Article: Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight ((‘Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight’, Los Angeles Times, January 1915.))

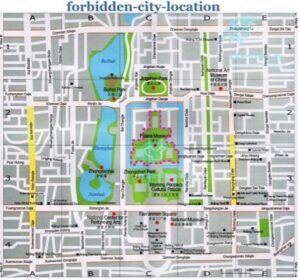

Newspaper Article: Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight ((‘Novel Features of Fair to Astonish and Delight’, Los Angeles Times, January 1915.)) Figure 1. The replica of Beijing’s ‘Forbidden City’.

Figure 1. The replica of Beijing’s ‘Forbidden City’.

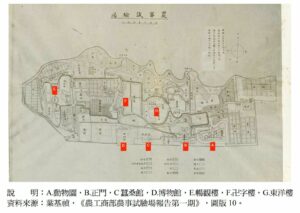

Figure 1. Map of Jingshan Park and the Forbidden city

Figure 1. Map of Jingshan Park and the Forbidden city

Figure 3. The restored Buddha statue in Wanchun Pavilion

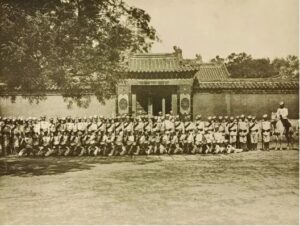

Figure 3. The restored Buddha statue in Wanchun Pavilion Figure 4. Russian Occupation of Jingshan Park, 1900

Figure 4. Russian Occupation of Jingshan Park, 1900