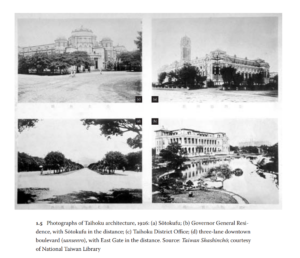

Figure A: Colonial buildings of Taipei.

At first I struggled to understand Michel Foucalt’s theory on Heterotopia, a theory which states that spaces have multiple meanings or relationships that do not immediately meet the eye. Yet, upon completing the prescribed chapter within ‘Taipei: city of displacements’ the idea of Heterotopias all fell into place. As Foucalt states, these spaces are found in all communities and in the case of Taipei this can be seen in the colonial administrative buildings built by the Japanese. These grand buildings as seen in Figure A are based upon European architectural design, announcing to the inhabitants of Taipei the colonial power of the Japanese. These spaces are designed to imply a colonial utopia, demonstrating the superiority of the Japanese as well as their efforts to modernise. It is interesting to note that following World War II, these buildings were adopted by the Chinese national government and took on another meaning. The buildings’ Japanese colonial history was expunged and instead the buildings became symbols of power for the national government. The reason I highlight this is that it offers an excellent example of Foucalt’s second principle within his theory on Heterotopia, demonstrating the impact of the passing of history on society.[1] What is important to understand here is that Heterotopia’s function can change over time as society develops.

My curiosity was piqued from having made the connection between Taipei’s colonial buildings and Heterotopias and so, I decided I wanted to find some more examples to be able to explore Foucalt’s theory. Focusing upon colonial buildings still, I stumbled upon an article by Maggi Leung titled the ‘Fates of European Heritage in Post-Colonial Contexts: Political Economy of Memory and Forgetting in Hong Kong’ and found an excellent case study in Star Ferry pier and the Queens pier. As Foucalt states in his third principle, Heterotopias can juggle multiple spaces, sites which are incompatible with one and other.[2] These piers proved to be exactly that, offering spaces for the people of Hong Kong to ‘express their sense of local, national and global citizenship.’[3] The Chinese, on the other hand, saw them as symbols of British colonialism.[4] I can be seen that as mirrors of society, heterotopias can represent many different mental spaces, where the eye of the beholder plays an important part in unlocking certain spaces. This is demonstrated by the difference in meaning of the piers from a Chinese and Hong Kong perspective.

The power of heterotopias as imagined spaces is represented in the picture below, highlighting not only the variety of mental space, as seen by the plethora of buildings, but also the potential for change and decay as society evolves.

Figure B: Heterotopia in summary.

[1]Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias (1984), p. 5.

[3]Maggi W. H. Leung, ‘Fates of European Heritage in Post-Colonial Contexts: Political Economy of Memory and Forgetting in Hong Kong’, Geographische Zeitschrift 97:1 (2009), p. 34.

Bibliography: